News

Interview with Elizabeth Mossop

Elizabeth Mossop. Image credit: Spackman Mossop + Michaels

Elizabeth Mossop. Image credit: Spackman Mossop + Michaels

Since becoming the director of the School of Landscape Architecture at Louisiana State University (LSU), you focused on bringing the Delta Region back after Hurricane Katrina. You’re on the board of LSU’s Coastal Sustainability Studio, which features a great mix of scientists, engineers, and designers focused on designing more sustainable systems and increasing resiliency within the region. One project you’re involved in, Bayou Bienvenue, calls for restoring the critical wetland forests that once protected the city. Other ecologists have noted that the Yucatan Region of Mexico recently fared much better when confronted with major storms because they left their mangroves in place. In the case of new Orleans, manmade infrastructure took the place of wetlands and ended up failing, causing the loss of life and destruction of communities. What challenges are you running up against in your efforts to bring back wetlands as coastal protection? What will it take to actually make this happen?

The destruction of the coast is a process that’s been in place for a long time, partly because of the loss of sediment from the Mississippi Delta, but also because of the real lack of regulation and the impact of the oil and gas industry throughout the whole Gulf Coast. At this point, it’s probably not a matter of being able to restore the coast or halt coastal erosion but really a question of thinking in a much more strategic way about how to balance out the demands of settlement against the sort of investment that’s needed to really make intelligent protection in the future. In other words, what will it take to make resilient communities sustainable in this very dynamic landscape? This would include strategies for retreat in some instances, as well as strategies for armoring or defense in others, and strategies so settlements can accept periods of flooding. A whole range of place- and community-specific solutions are required that integrate urban development strategies with real understanding of natural processes and dynamic change.

Working with the Coastal Sustainability Studio has been interesting in this context because of its multidisciplinary approach, bringing together scientists and engineers with designers. At the regional scale, we have looked at new strategies for river diversions in order to increase the deposition of sediment for land-building. This is an enormously productive direction for future work, trying to harness the power of the river for restoration, as well as combining this with broad-scale restoration of the indigenous coastal swamp and marshland communities.

However, the impediments to this type of approach are myriad. On the one hand, at the federal level, there is the Army Corps of Engineers with tremendous resources and power but an entrenched culture of traditional engineering and a very limited focus. From the state’s perspective, there is little appetite for the kind of integrated strategic planning and investment required for long-term conservation and development strategies. The hurdles are significant, but it’s enormously valuable to simply try to put alternatives out there and make information publicly available as a means of trying to influence the discourse.

While New Orleans rebuilds, we must also be prepared for the next, perhaps inevitable, storm. How can natural systems be used in preparation for the next storm event? What can landscape architects do to help the city and others like it bolster their preparations?

Landscape architects are uniquely placed to help cities prepare for natural hazards and mitigate their impacts. Certainly, we need to look at restoration and strengthening those natural systems that historically have provided really significant protection. In the case of New Orleans, the value of marshlands and cypress swamps, particularly to the east and south of the city, are incalculable.

As you know, one of the things that happens in storm events is a massive loss of canopy. We know a lot more now about the effectiveness of different species in terms of resilience to storms. On that smaller scale inside the city, re-planting of canopy can be fine-tuned with this knowledge to be more resilient. It's really just thinking about a more integrated approach to storm protection and the design of everything in this city, from streets to water infrastructure, and how to make these systems more robust. For example, we can look at the technical design of road pavements that will be more resilient to inundation. A lot could be done to allow the city, which is very sparsely settled now, to absorb and hold a lot of water, mitigate against flooding, and take the pressure off the drainage and pumping systems. This could be achieved through the design of new parks and open space in combination with water and road infrastructure.

One of your award-winning projects, Scout Island, a 62-acre site located within City Park in the heart of New Orleans, was a wilderness preserve and bird-watchers’ paradise before Hurricane Katrina. In your effort to restore the area, you’re tagging and removing exotic species, giving the chance for the native ecosystem to come back. Why is restoring the native ecosystem so important for the park’s long-term survival? Will these native species fare better in another major storm?

I’m not certain indigenous species are necessarily any more resilient to storm damage, but this is really about a much longer-term strategy for the park. This area is one of the few even partly natural areas anywhere in the city and provides an incredibly significant resource both as habitat, particularly to migratory birds, but also a really significant educational resource, especially for schools and programs for inner-city kids and the general public. The potential is there for educational activity and nature-based recreation to become even more significant. Although City Park is enormous, this is a significant area of land within the park, and the only area which performs this nature education and adventure role. The other aspect of this is the restoration of the indigenous forest, restoring its biodiversity and preventing the site from becoming completely dominated by a monoculture of Chinese tallow, which is what our current work aims to prevent.

Scout Island Strategic Plan, New Orleans, LA. Image credit: Spackman Mossop + Michaels

Scout Island Strategic Plan, New Orleans, LA. Image credit: Spackman Mossop + Michaels

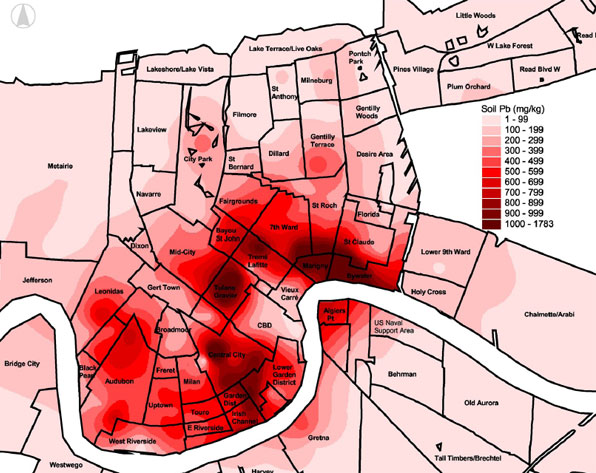

New Orleans also suffers from toxic, lead-ridden soils. Mel Chin, artist and provocateur, has launched his Operation Paydirt and Fundred Dollar Bill projects to help raise national awareness of the soils issue in New Orleans. He says $300 million will be needed to clean up the lead, but he says it’s worth it given that "30 percent of the population is poisoned before they reach adulthood." What would be the most cost-effective way to translate this vision into action using the brownfield lots within the city? What role can landscape architects play?

Funny you should ask because my firm worked with Mel Chin on that project for a long time and I would love to see it come to fruition. He basically had three teams: an art team, a science team, and we were the implementation team, working with Dan Etheridge (of Meffert Etheridge environmental consultants). Julie Bargmann of Dirt Studio had also worked on the earliest stages of that project with Mel and helped him think through how the idea could play out in an urban landscape by creating a series of park/depots at different scales. We then took on the task of trying to figure out how to develop an implementation strategy for the city. Our approach was to use it as a tool for urban revitalization, obviously as a means of getting the contaminated soil out of those residential neighborhoods, but also as a way of participating in the process of economic revitalization for these areas. The statistics on the effects of lead contamination in New Orleans are frightening.

New Orleans Neighborhood Lead Concentrations (2005) / Image credit: Operation Paydirt / Fundred Dollar Bill

New Orleans Neighborhood Lead Concentrations (2005) / Image credit: Operation Paydirt / Fundred Dollar Bill

Our proposal involved creating a central manufacturing and distribution center for the city to distribute Mississippi sediment and manufacture soil using large-scale green waste composting. The idea was also to maximize local job training and creation. There would also be a series of resource depots strategically located on vacant land throughout the city. These demonstration sites would provide materials and training to homeowners as well as resources for urban greening generally. As the lead mitigation was completed in the surrounding neighborhoods, the sites would transition into other uses as parks, urban farms, and campuses. We had started talking to some of the more entrepreneurial people in New Orleans, who are involved in metropolitan scale distribution systems and were also looking at identifying suitable depot sites. At his point, we just need the $300 million and we’re ready to go.

Another one of your award-winning projects focused on creating an urban farm and community center for the local Vietnamese community in New Orleans, including community gardens and commercial farming plots, market pavilions, play areas, sports fields, recycling center and a major water collection and management system. How is the project going? Do you also see this as a model for how to reuse some areas of New Orleans and the broader region?

That project has hit some real roadblocks in terms of its implementation. There are certain complications with the site and its ownership and also with the permitting of it, so that it seems to have gone into a holding pattern. The Vietnamese community is currently investigating the possibility of using a different site. So, the project is eminently fundable and very highly developed at this point, but not actually moving forward. But it has so much potential for the eastern part of the city. Particularly with the elderly population of the neighborhood, you have a huge workforce of incredibly highly-motivated, highly-skilled farmers and gardeners. A lot of people are talking about community gardening and farming and small-scale agriculture as an opportunity for all this vacant land in New Orleans but in this location, we’ve actually got the workforce ready to go. You just look at the neutral ground or the median strip or whatever in their neighborhood; they’re gardening all of that already.

I think what makes that project so interesting as a model is the different layers of use. It’s very much about passing those farming and gardening traditions from the original immigrant generation to the young people in that community today. There are also real opportunities for them to get together and boost up the entrepreneurial component of the project. That’s also why it’s really interesting on a regional scale because it’s got so much potential with the market and food processing components to really create jobs and provide structure for a whole lot of small-scale economic activity, which the city needs desperately. It really does provide an interesting model for economic activity, productive landscape, community focus, recreation, and model environmental practices that can go together in different combinations for projects all over that region.

Viet Village Urban Farm, New Orleans, LA. Image credit: Spackman Mossop + Michaels

Viet Village Urban Farm, New Orleans, LA. Image credit: Spackman Mossop + Michaels

Through your firm, you’re working on Dwyer Canal, a project that would turn a drainage easement into a social space while also addressing local flooding issues. Do green infrastructure projects need to be designed first as social spaces or as stormwater management systems? Through the design process, how do you insure you hit all needs: social, environmental, economic?

This was a project funded for the local community organization. Their interest was really water management as the area suffers flooding on a regular basis. The project moved fairly slowly and had an extensive process of community engagement with meetings, workshops, and other activities. The site is an open corridor with a ditch in the middle. The community had an image from an earlier planning study showing the canal covered over and a path down the middle of the easement. We were coming at this from the point of view of thinking how to make this mitigate the flooding, make the water course into an asset, and turn it into the centerpiece of an open space project. Like many of these issues in New Orleans, nobody really understood what was happening with the water and the engineering. We were working with the engineers, Intutition and Logic from St. Louis, who did a real detective piece of work to find out what was happening. In fact, the situation in terms of the flooding was completely different from the way anybody understood it in the neighborhood or at the Sewerage and Water Board.

What has been really interesting over time was that the community group and the steering committee have been very involved in the process. We had spent a lot of time talking with them about the technical issues of the drainage, which they now completely understand and own. Through that process of negotiation, we came up with a hybrid scheme, which keeps the drainage channel open, and uses a whole series of artificial wetlands and detention basins to slow down the water and clean it, but we also have public facilities on either side of major pedestrian links that cover the water course for substantial areas, making them very easy, safe, and visible.

Dwyer Canal. Image credit: Spackman Mossop + Michaels

Dwyer Canal. Image credit: Spackman Mossop + Michaels

In this instance, the community members are now the project’s strongest advocates. They understand better what is happening than the people who are empowered to make those decisions. We really hope to see something very positive move forward out of this process

Lastly, moving downstream from these cities on the Delta, the Gulf of Mexico is one of the world’s most polluted bodies of water on Earth, in large part due to shipping activity and runoff from the communities in the region. A comprehensive green infrastructure approach could help reduce the amount of oil and chemical-laden runoff from moving towards the water. What kind of broad-based green infrastructure solution would you propose to deal with Gulf water pollution?

The real impacts on water quality come from upstream, as well as from the Gulf region, and so what is needed is a federal initiative to address the whole of the catchment. Currently there are both incentives and regulation to try and control polluted runoff into the Mississippi, but the nature and scale of the problem mean that the measures are too fragmented and not effective in preventing the problems. There are so many different organizations involved it is difficult to even share common language on the issues. It is also difficult to target the measures specifically at the most problematic polluting areas.

We think the most effective solution would be for the federal government to purchase land in key locations, where pollution is worst and hydro-geological conditions are most favorable, and create massive wetland buffers to prevent pollution entering the river. These wetland buffers could potentially be designed to perform other functions as well, harnessing excess nutrients for the production of algae, timber, fish and other aquatic species.

Coastal Wetlands. Image credit: Fish and Wildlife Service

Coastal Wetlands. Image credit: Fish and Wildlife Service

Elizabeth Mossop, ASLA, is professor of landscape architecture and former director of the Robert Reich School of Landscape Architecture at Louisiana State University. Mossop is also a principal at Spackman, Mossop and Michaels, which has won numerous ASLA professional analysis and planning awards.