News

Interview with Jaime Lerner

Image credit: Jaime Lerner Associated Architects

Image credit: Jaime Lerner Associated Architects

In your talk at a conference organized by The Economist, you argued that cities are the solution to climate change, not the problem. What is the case for this?

Well, my point of view is that there are many, many answers to what would be the best way to avoid climate change. A lot of people are talking about new materials. Or new sources of energy. Or wind turbines. Or recycling. They're really important but not enough. Everything is very, very important, but not enough. When we realized that 75 percent of car emissions are related to the cities, we realized we can be more effective when we work with the concept of the city. It's through cities that we can have better results.

When you were mayor of Curitiba, you devised a number of low-cost solutions that turned your city into a model green community where people also have incomes 60 percent higher than the Brazilian average. What kind of investments did you make in green space? What do you see as the relationship between livability and sustainability?

If you want creativity, cut one zero from your budget. If you want sustainability, cut two zeroes from your budget. And if you want solidarity, assume your identity and respect others' diversity. There are three main issues that are becoming important, not only for your city, but for the whole of mankind. These relate to three key issues in cities: mobility, sustainability, and tolerance (or social diversity).

On infrastructure, there's always the assumption that the government has to provide public transport. Every time we try to create a solution, we have to have a good equation of co-responsibility with the public. That means it's not a question of money and it's not a question of skill; it's how do we organize your equation of co-responsibility?

For example, when I was governor we had to work hard to avoid reduce pollution in our bays. Of course, it's very expensive to do environmental clean-up work and we didn't have the money. Another region had taken out a huge loan from the World Bank, about $800 million. For us though, the question wasn't about money; the question was about mentality. We didn't have that money so we started to clean our bays through an agreement with fishermen. If the fisherman catches a fish, it belongs to him. If he catches garbage, we bought the garbage. If the day was not good for fishing, the fishermen went to fish garbage. The more garbage they catch, the cleaner the bays became. The cleaner the bay is, more fish they would have. It that's kind of win-win solution we need. We need to work with low-cost solutions. And, of course, in public transport, we also organized a good equation of co-responsibility with the public.

Fisherman onshore collecting garbage. Image credit: Jaime Lerner Associated Architects

Fisherman onshore collecting garbage. Image credit: Jaime Lerner Associated Architects

As mayor of Curitiba, you also created the world's first bus rapid transit system (BRT), "Speedy Bus," which works like a surface subway system but at far less cost. How did you come up with this highly sustainable transportation solution? How did you form the public-private partnership that made it cost-effective?

We didn't have the money for a completely new fleet, which would have cost $300 million. What was the equation? What was the solution? We said to the private sector, private companies, we'll invest in the itinerary as long as you invest in the fleet. We'll get loans for the work on our side, for public works, for the itinerary if the private sector gets loans for the fleet. We paid them by kilometers and there are no subsidies. The system pays for itself. Now, there are more than 83 BRT systems around the world.

Curitiba Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Stations. Image credit: Jaime Lerner Associated Architects

Curitiba Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Stations. Image credit: Jaime Lerner Associated Architects

The problem is in many countries, government wants to invest in everything. That doesn't work. I'll give you an example. Why don't we have a good system of transport in New York on the waterfront? This could be a very good approach for reducing congestion in the city's bridges and tunnels. The city could have a very pleasant system of water public transport. But instead, the policymakers are holding it up, saying there are no passengers and we don't want to invest in the fleet. First, they need to create a good partnership and create an attractive system, then they will have the passengers, and then they will have a low-cost solution. However, if don't have passengers to make it feasible, it's much more costly.

You also mentioned that many poor copies of your BRT are out there, and are actually setting back BRT as a transportation movement. What are other cities doing wrong? Who are the worst offenders? Why is it hard to get this system right?

BRT can't be designed as a transportation solution. It has to be planned as a whole city. Why? Because the city is a structure of living, working, and leisure. Everything together. Transportation has to provide a structure for living and working together. It can't just be a system of transport. You will just have a kind of commuting system, which is more difficult to make feasible. Cities always need to approach transportation as providing a structure for living and working. It's not about living here and working in some other place. With that kind of approach, you will only use public transport twice daily, concentrated in just a few hours. If you have a system that works always and connects working and living activities, it's more a city than just a corridor of public transport.

You were also known for innovations in the delivery of city services. One program to clean up dirty, narrow streets that were inaccessible to trash collectors gave residents bags of groceries or transit passes in return for their garbage. You decentralized garbage collection. How well did this program work? Have other cities taken up this approach?

It's been working for more than 20 years in Curitiba. In many cities, there are places where it's difficult to provide trucks access to collect garbage. In many cities, if the slums are on the hills or deep in valleys, they're difficult to access. In these places, people are throwing away their garbage and polluting the streams. Their children are playing in polluted areas. In 1989, we started a program where we said, Okay, we're going to buy your garbage as long as you put your garbage in a bag, and bring it to the trucks, where it's more accessible. In two or three months, all these areas were clean, and these very low-income people had an additional source of income.

We also started a public education programs on the separation of garbage because we realized that we could transform one problem if we separated garbage in every household. We started teaching every child in every schools. Children taught their parents. Since then, Curitiba had the highest rate of separation of garbage in the world for more than 20 years. Around 60 or 70 percent of families are separating their garbage at home.

Now you have your own architecture and urban design firm and you are working with major city governments and private clients throughout the Americas. I saw you were designing a few projects that reuse transportation infrastructure and turn highways into elevated parks, much like the High Line. What kind of projects are you working on? How are you trying to reuse infrastructure?

Sustainability is an equation between what we save and what we waste. There are so many problems of mobility or integration of systems, but we have to work fast. If we understand the city as a structure of living, working, moving together, we can work more effectively. It's very difficult to have a complete network of subways in many cities of the world. Even if I believe that the future is on the surface, my idea is not trying to prove which system is the best, but using what you have. For instance, in Sao Paolo, they have three subway lines. They are working on fourth line of the subway, with 84 percent of the trains are running on the surface. It's the surface that has to operate better. At the same time, the suburb railroad is being improved.

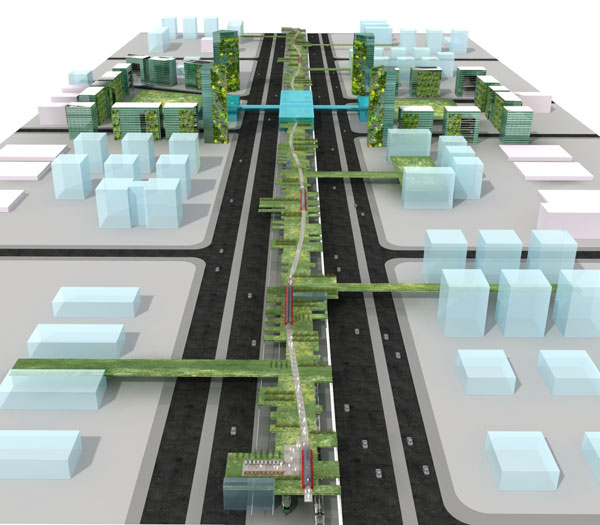

The idea is to take advantage of the existing path of the suburb railroads and build above the rail a kind of linear park like the High Line. However, this linear park would link the whole city, where you can connect people of all income levels. In every place, you could have good public transport and you a huge park linking it all. Within this park, you could walk, bike, or take small electric car. That's the idea that we presented for the city of Sao Paolo with the private sector and public sectors.

Sao Paulo elevated parks concept. Image credit: Jaime Lerner Associated Architects

Sao Paulo elevated parks concept. Image credit: Jaime Lerner Associated Architects

Sometimes there's an idea and it has to be improved. We have to understand that innovation is fast and leaves room for the idea to be improved. We're trying to work fast in many cities and provide them with a good start. In other cases, we use "urban acupuncture." These are small interventions that can provide new energy to the city, and provide assistance during the process of long-term planning, which has to take time. But we have to work fast.

At the street level, you've been experimenting with portable streets, which you say can enable vendors to set up easily anywhere, creating informal and spontaneous market street life. Why do we need this infrastructure?

Some places in some cities have become decayed. There's no life. When that happens, it's very difficult to bring back life because people don't want to live in a place like that. However, the moment we bring street life, people will want to live there again. That's why we designed the portable streets. On a Friday night, we can deliver a portable street and remove it Monday morning. We can put a whole street life in front of a university or any place, bringing street life back.

Portable Streets. Image credit: Jaime Lerner Associated Architects

Portable Streets. Image credit: Jaime Lerner Associated Architects

Beginning in 1971, Jaime Lerner was elected Mayor of Curitiba, re-elected two more times, and then served as Governor of Paraná, Brazil. Lerner has won a number of major awards for his transportation, design, and environmental work, including the United Nations Environment Award; the Prince Claus Award, given by the Netherlands; and the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Medal in Architecture, given by the University of Virginia. In 2002, Lerner was elected president of the International Union of Architects. Lerner is principal of Jamie Lerner Associated Architects.

Interview conducted by Jared Green.