Advancing Trauma-Informed Landscape Architecture

Honor Award

Research

Raleigh, North Carolina, United States

Lauren Joca, Associate ASLA;

Faculty Advisors:

Celen Pasalar;

North Carolina State University

This is a growing field which lacks understanding of the area of design. The submission is being commended on the development and understanding that this type of design is emotional and different.

- 2023 Awards Jury

Project Statement

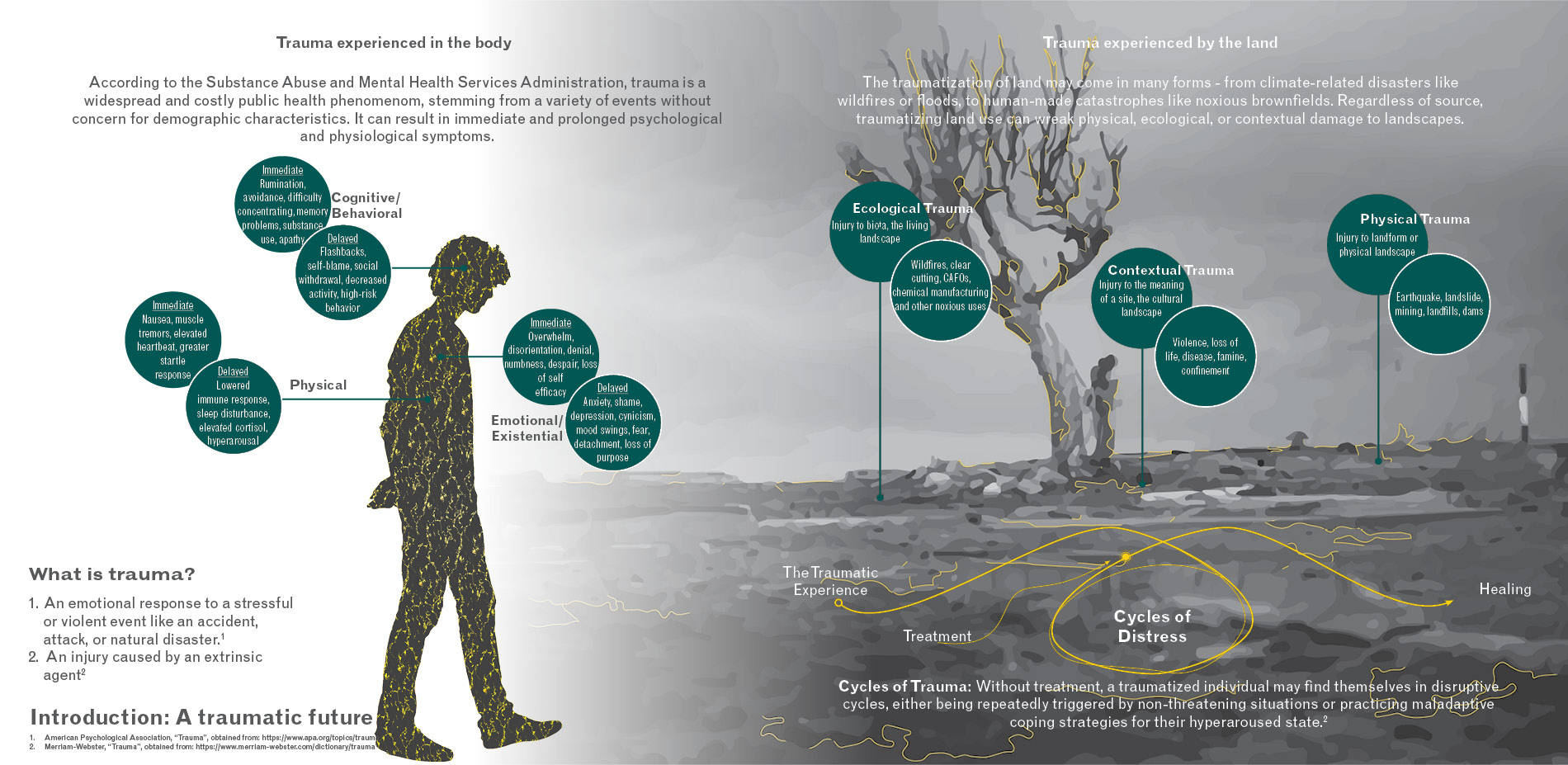

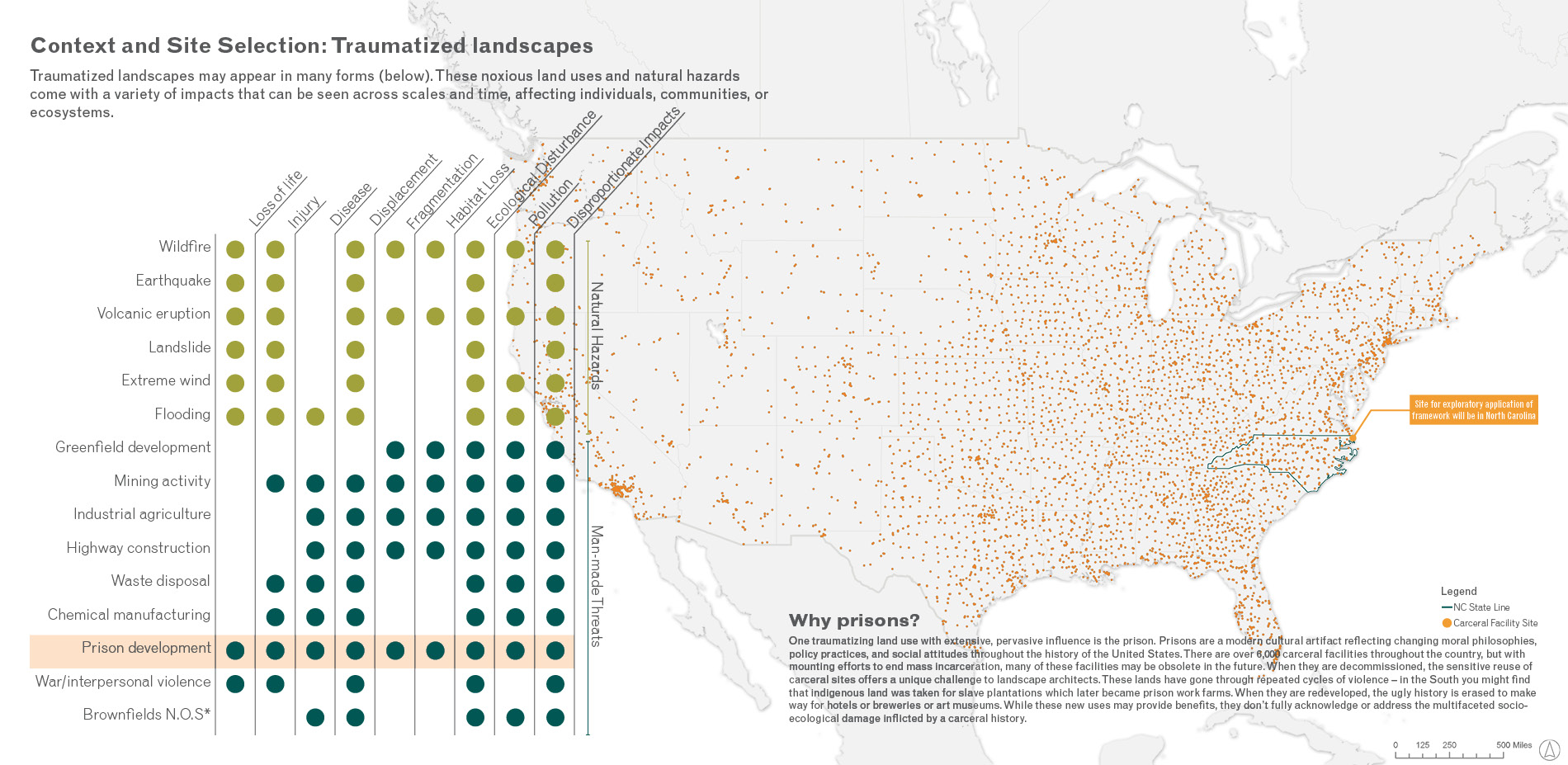

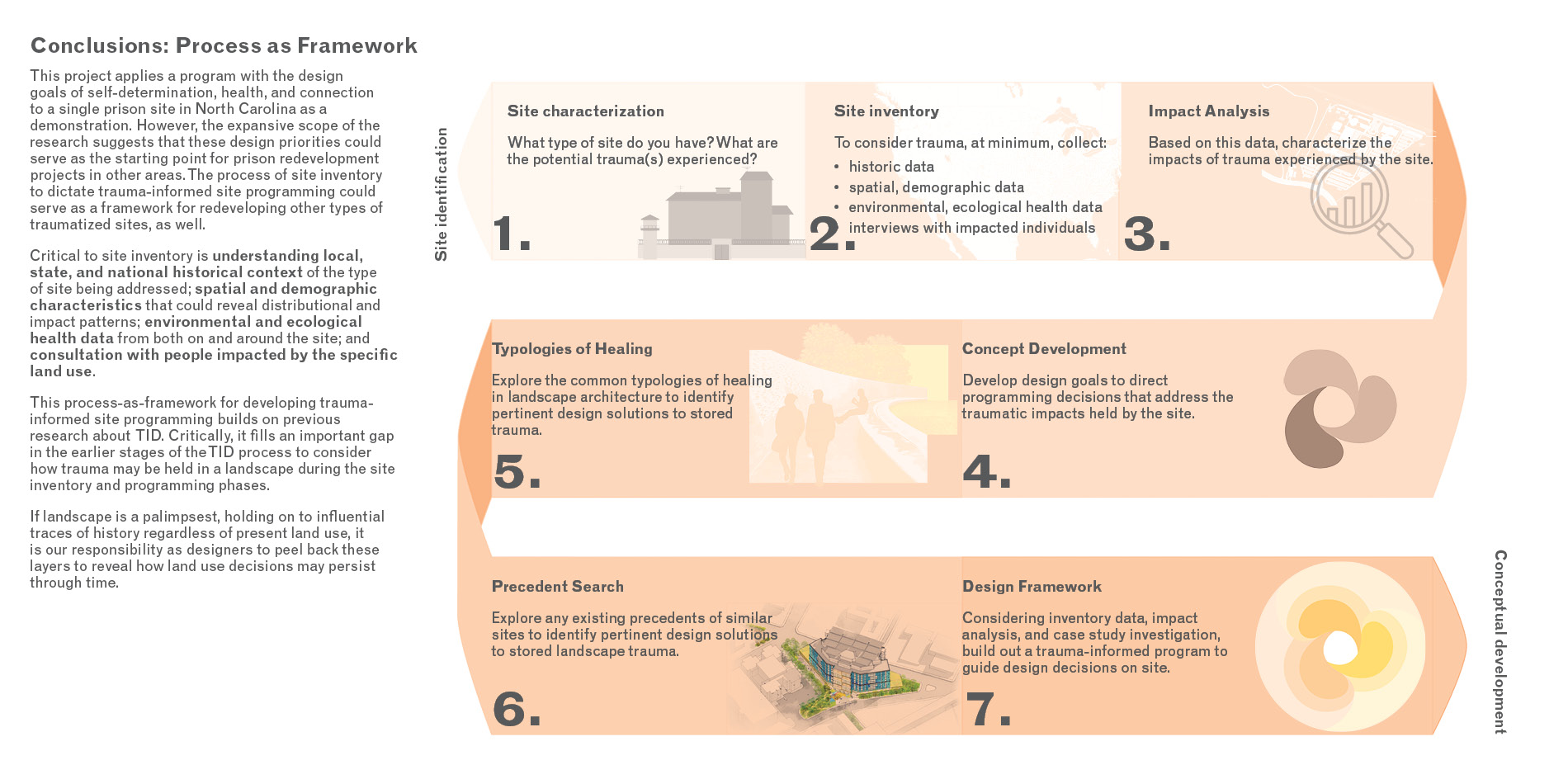

Communities are challenged with climate change, habitat loss, and social conflicts resulting in trauma experienced by individuals and held in the land. Traumatizing land use causes physical, ecological, or contextual damage to landscapes. Sites cannot be healed without understanding and rectifying the trauma imposed on the land. This research explores the site elements that are essential to understanding landscape trauma. It also examines how a revelatory site inventory can produce trauma-informed site programming. Using prisons as an example of traumatized sites, the study identifies programming priorities that promote strategies for healing. The framework developed has the potential to apply across a variety of traumatized land uses.

Project Narrative

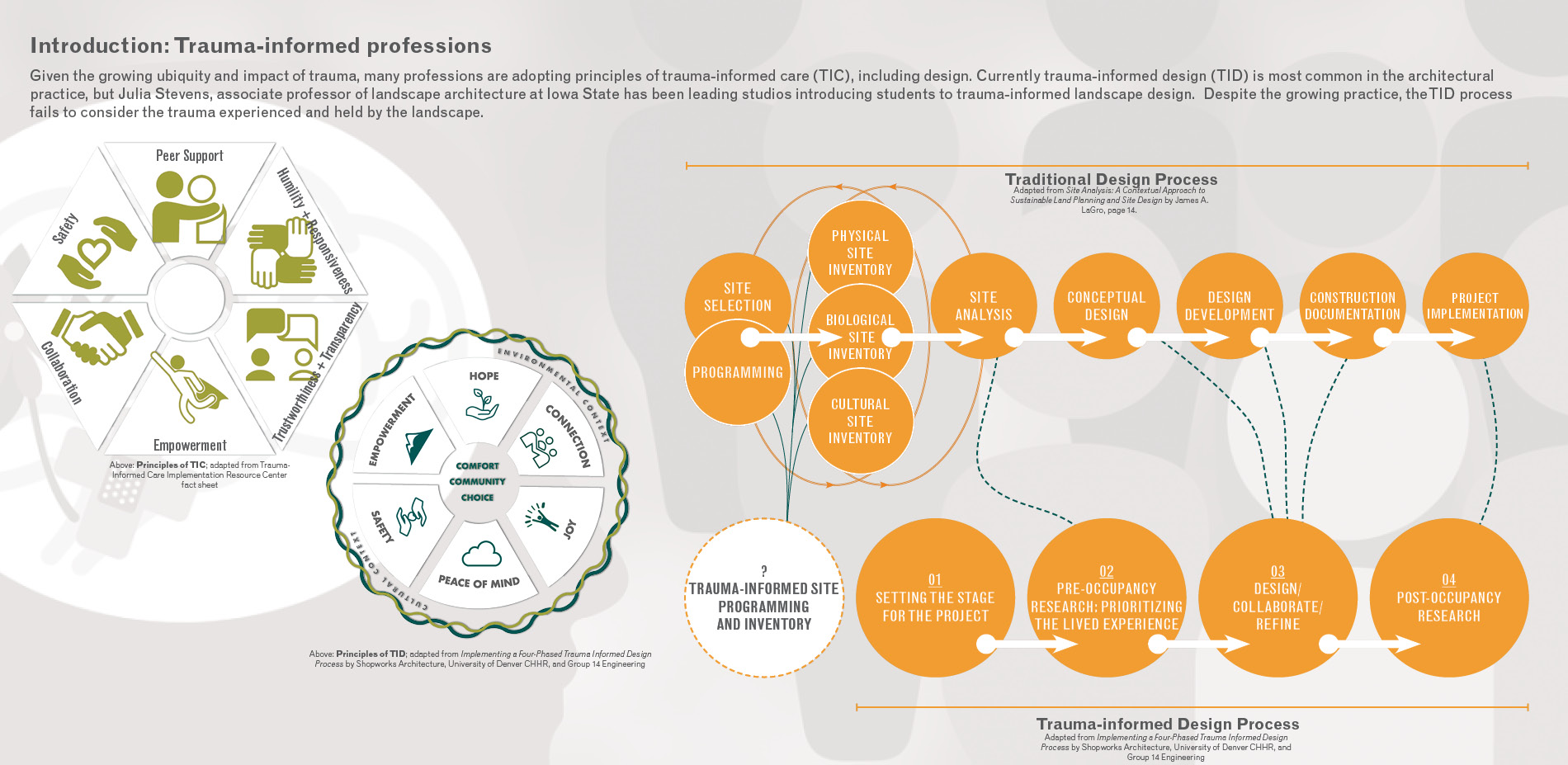

Growing threats like climate change, habitat loss, disease, and social conflict are leading society toward a precarious future. Accordingly, the landscape architecture profession created a new landscape declaration in 2016, promising to “create places that serve the higher purpose of social and ecological justice for all peoples and all species.” To achieve this goal, we must acknowledge what these threats will introduce into communities: TRAUMA. Although trauma-informed design (TID) is a growing subset of the field, it relates to decision-making with a focus on the trauma experienced by individuals. It fails to consider the trauma experienced by and held within the land that may come from climate-related disasters or human-made catastrophes like noxious brownfields. Regardless of source, traumatizing land use can wreak physical, ecological, or contextual damage to landscapes.

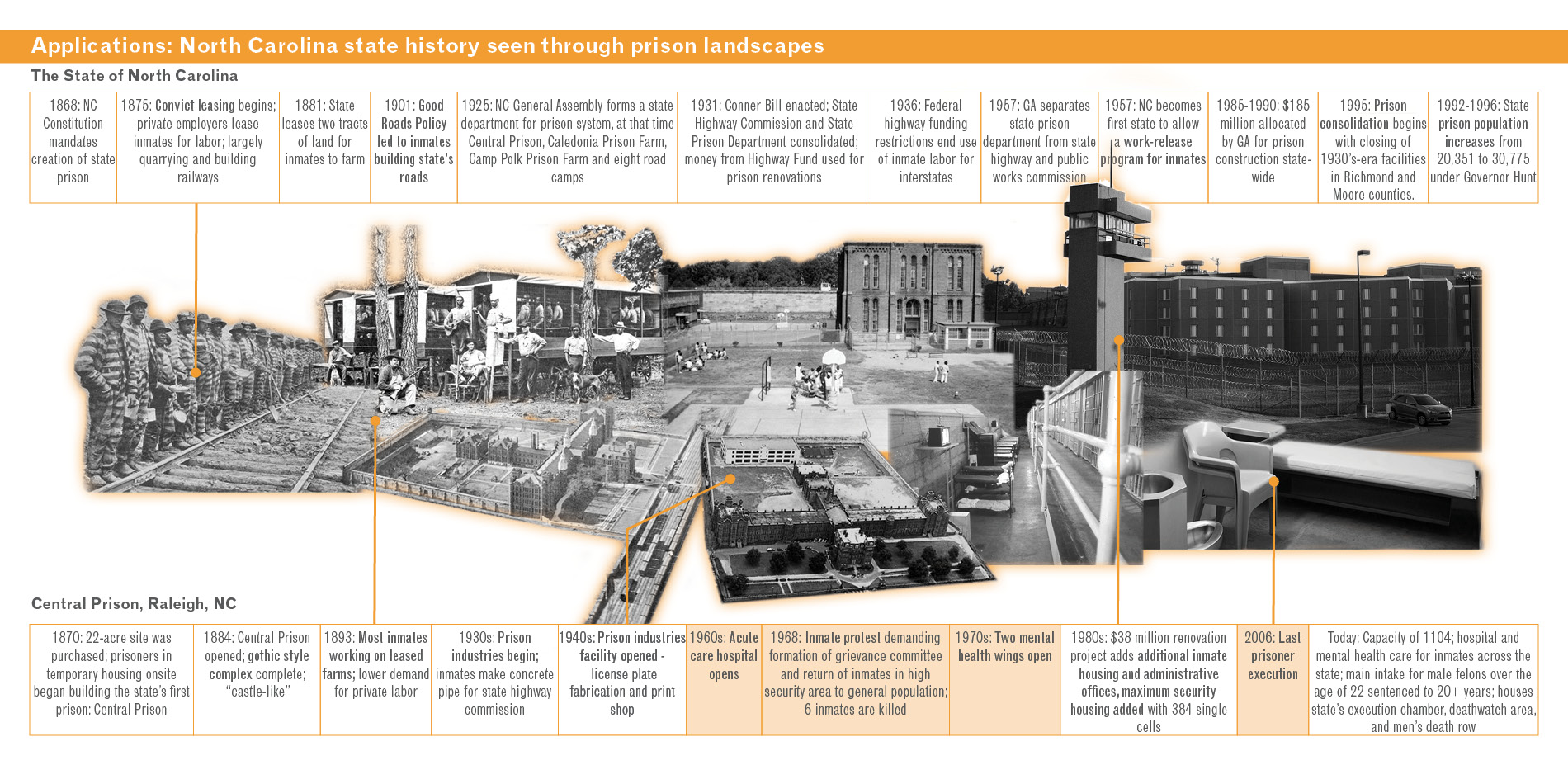

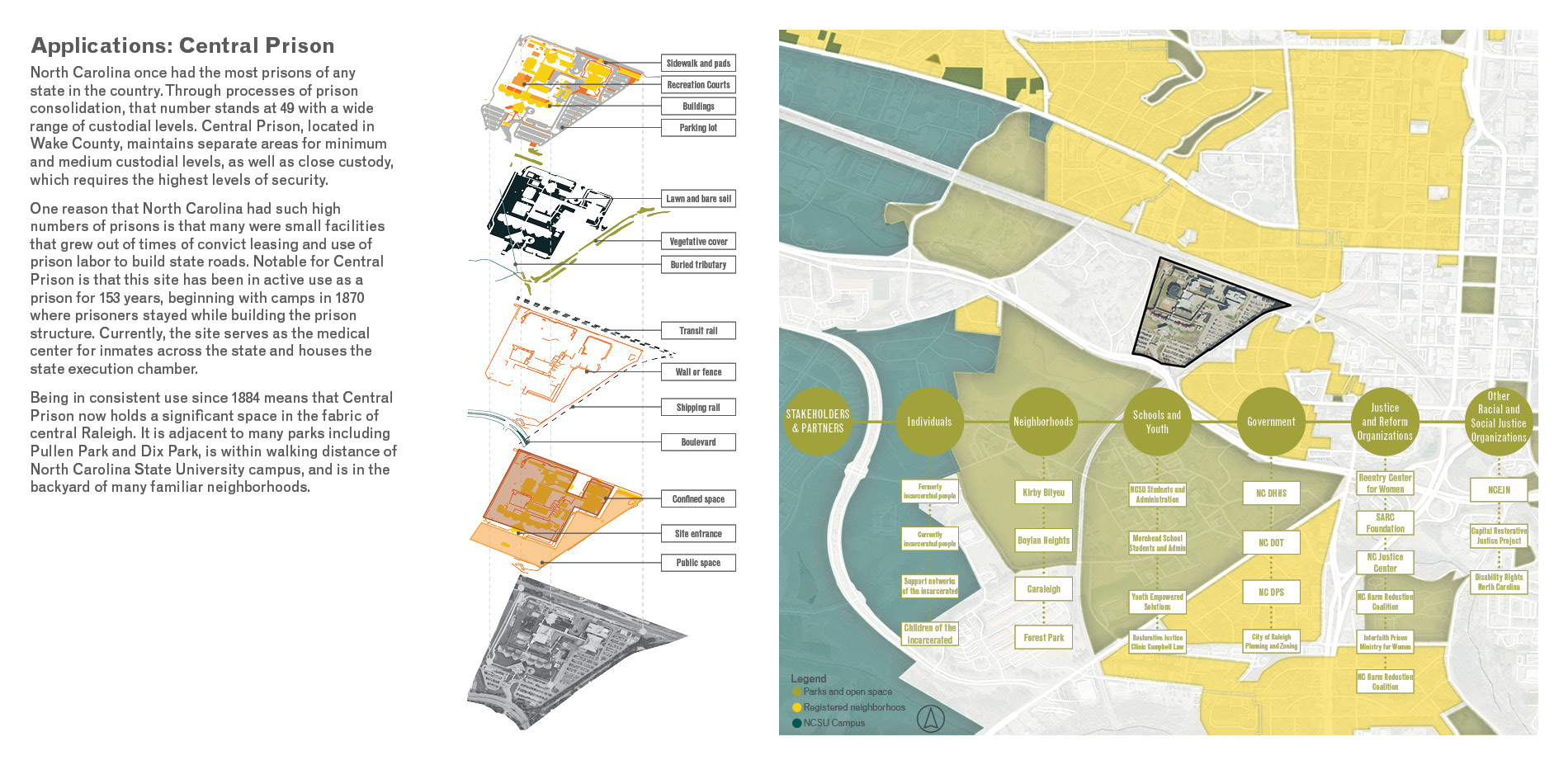

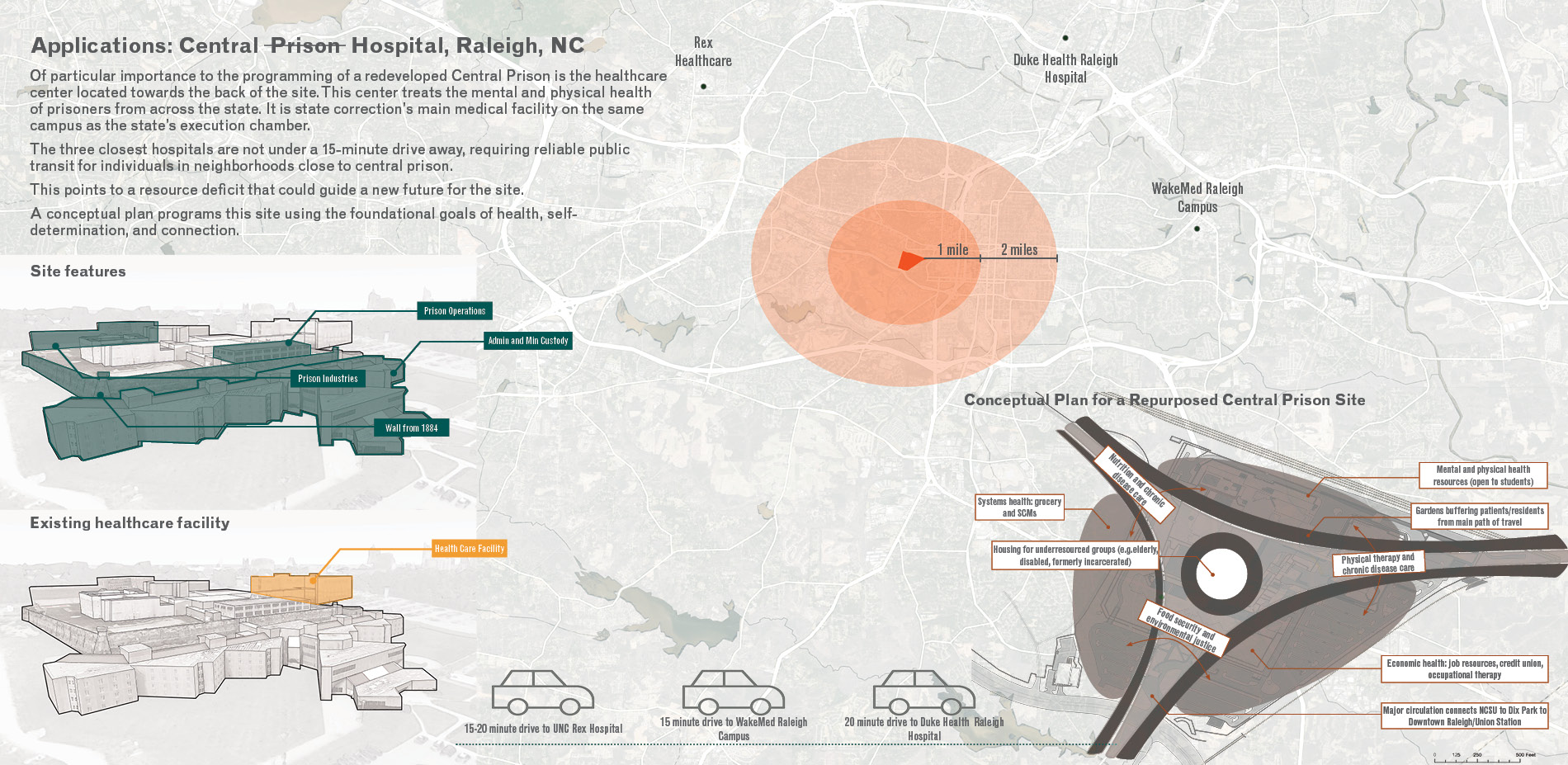

One such land use with pervasive influence is the prison. Prisons represent the changing moral philosophies, policies, and social attitudes throughout the history of the US. With efforts to end mass incarceration, more prisons may be decommissioned. The sensitive history and reuse of such sites offer a unique challenge where the multifaceted socio-ecological damage inflicted by a carceral history should be acknowledged.

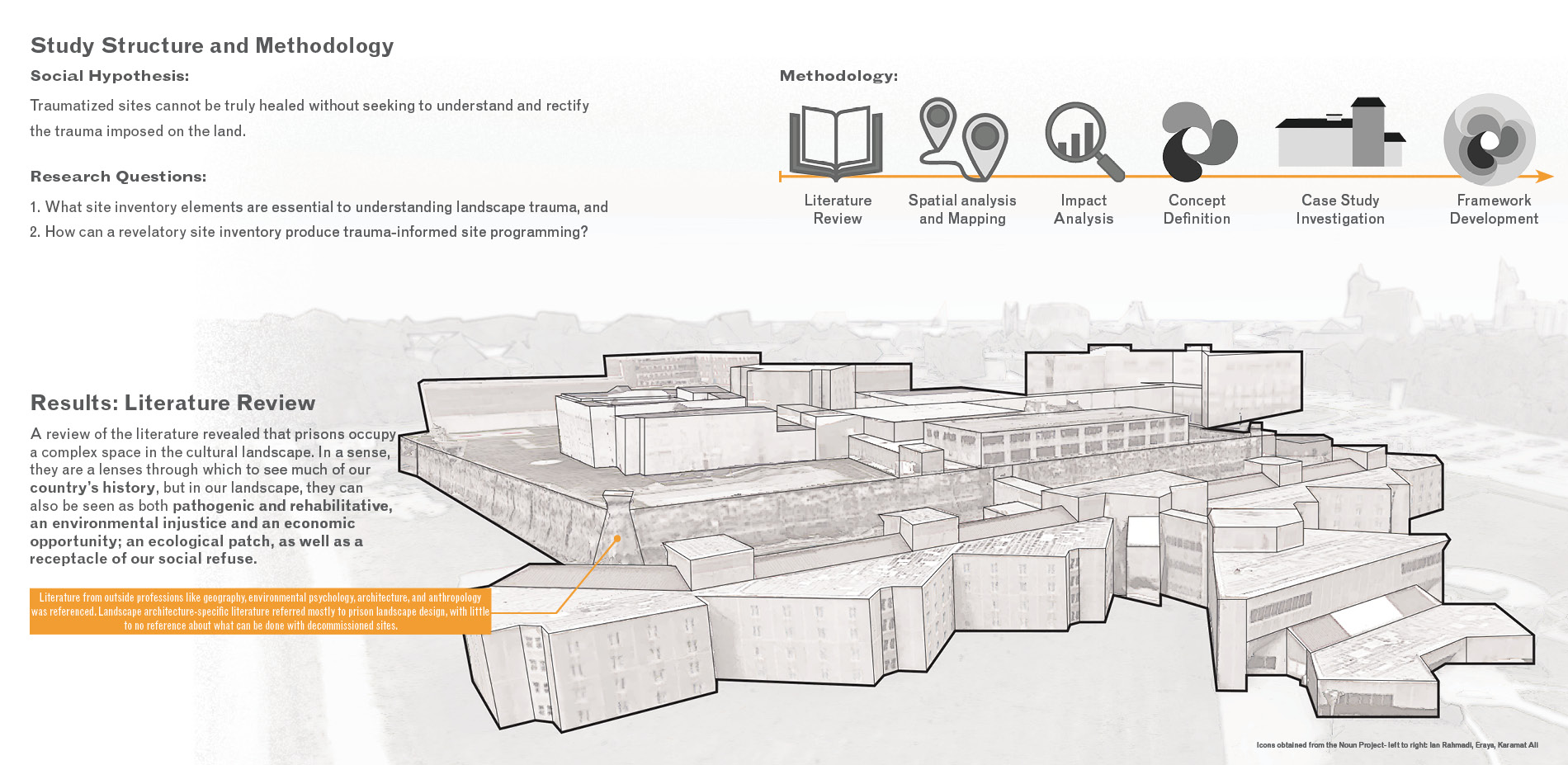

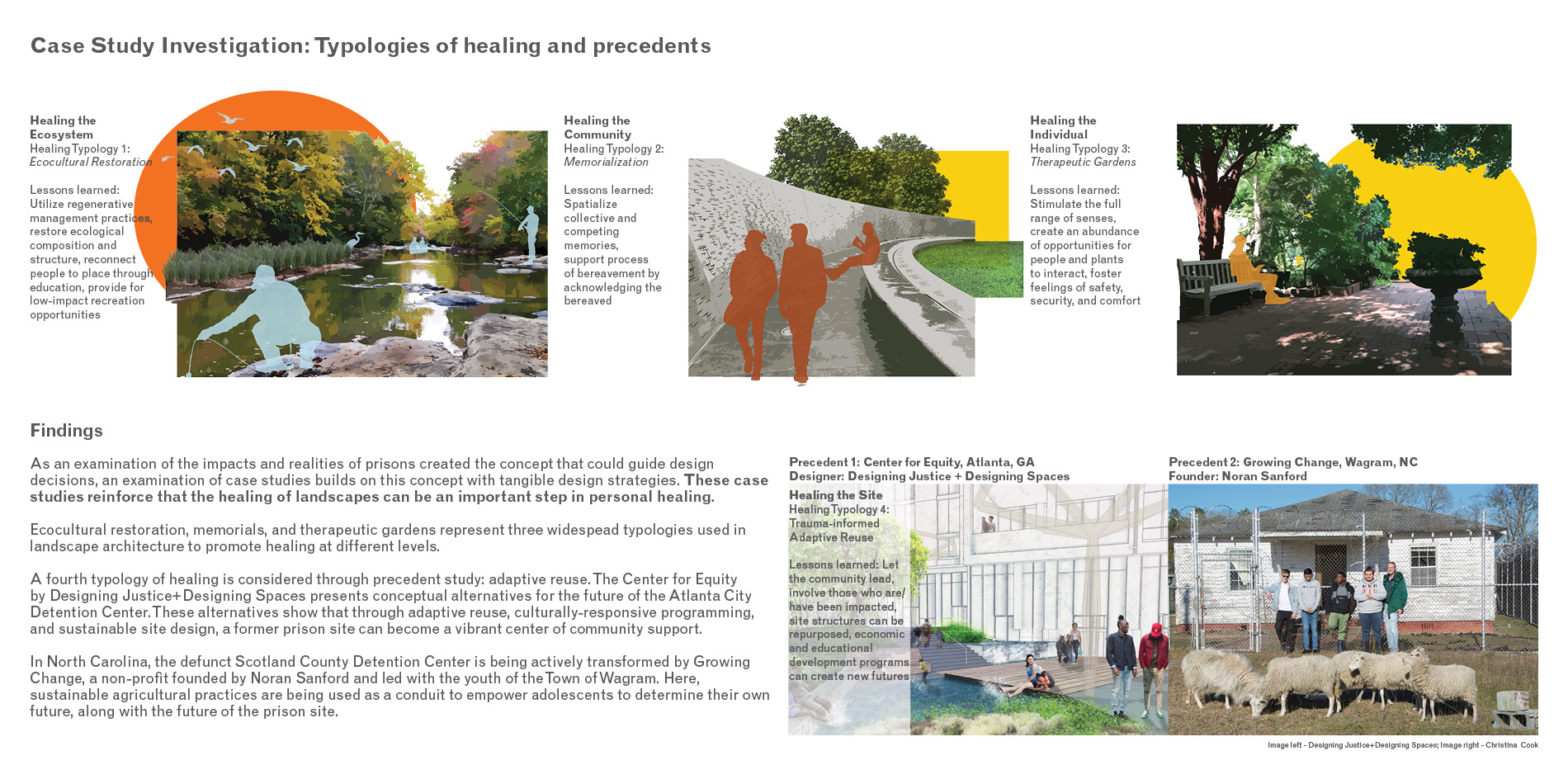

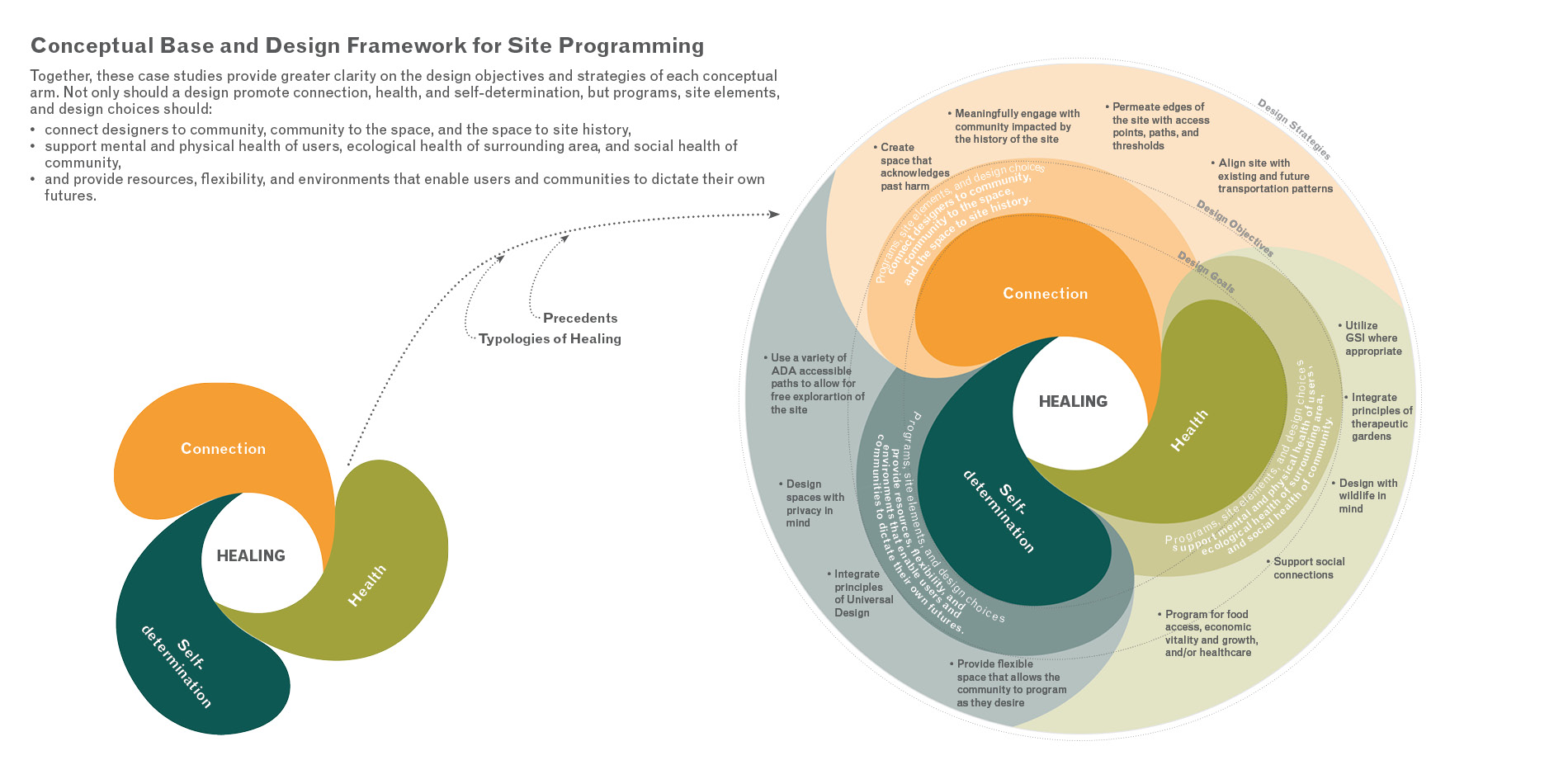

It is my social hypothesis that these sites can’t be healed without understanding and rectifying the trauma imposed on the land. Therefore, this research asks (1) what site inventory elements are essential to understanding landscape trauma, and (2) how can a revelatory site inventory produce trauma-informed site programming? Using prisons as an example, the study uses spatial mapping, impact analysis through literature review, and case study investigation. It also identifies programming priorities that promote strategies for healing.

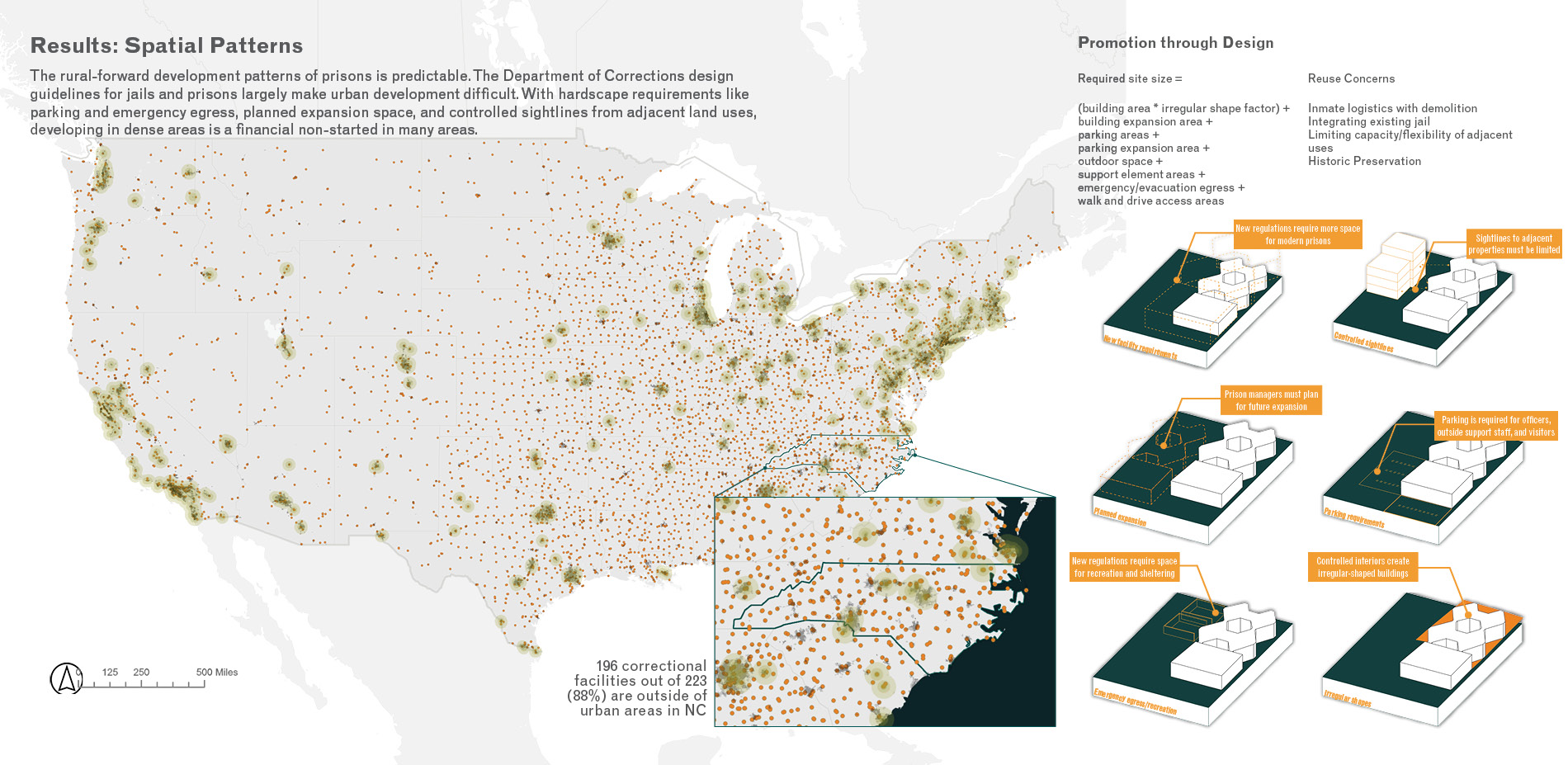

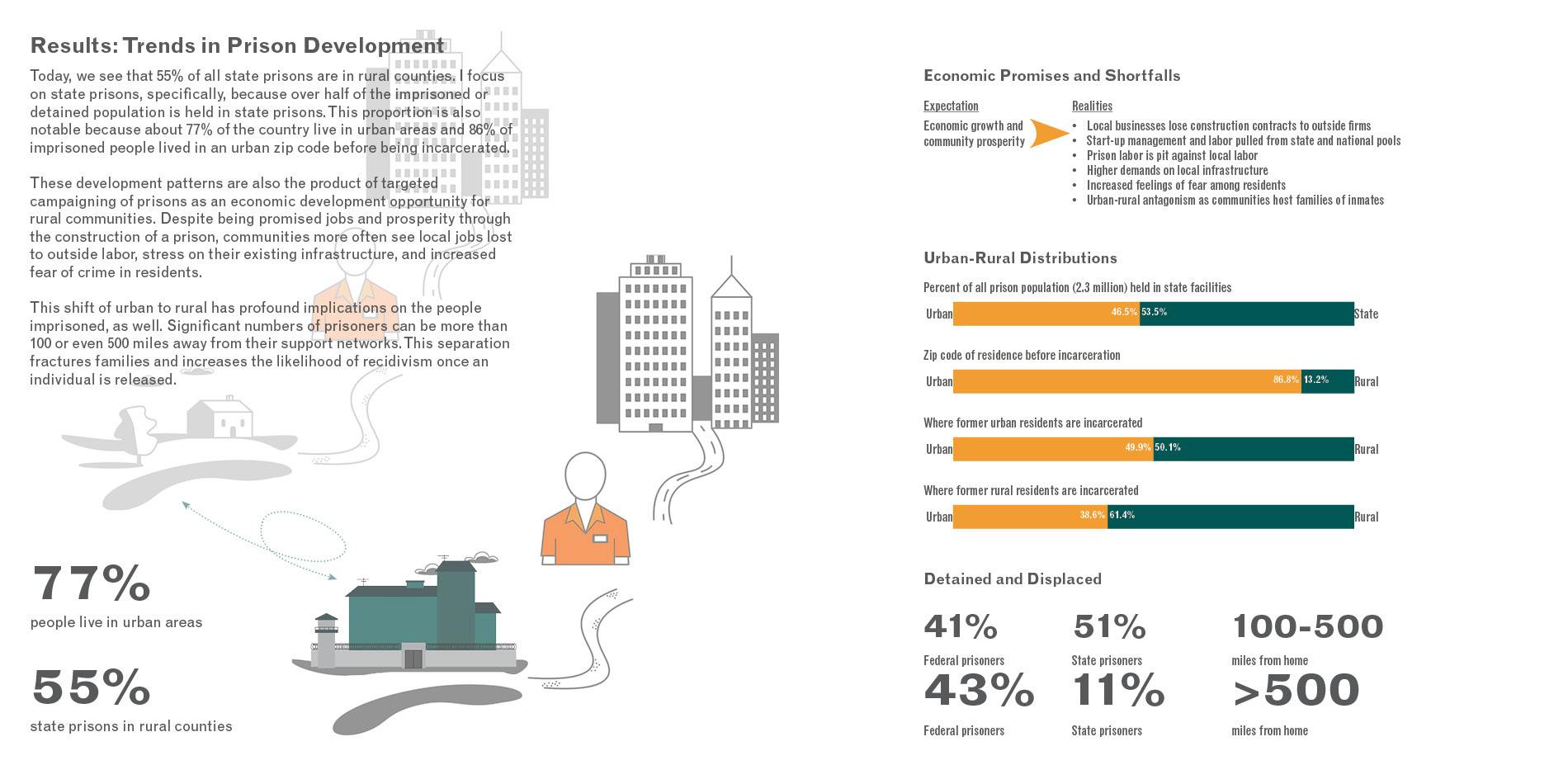

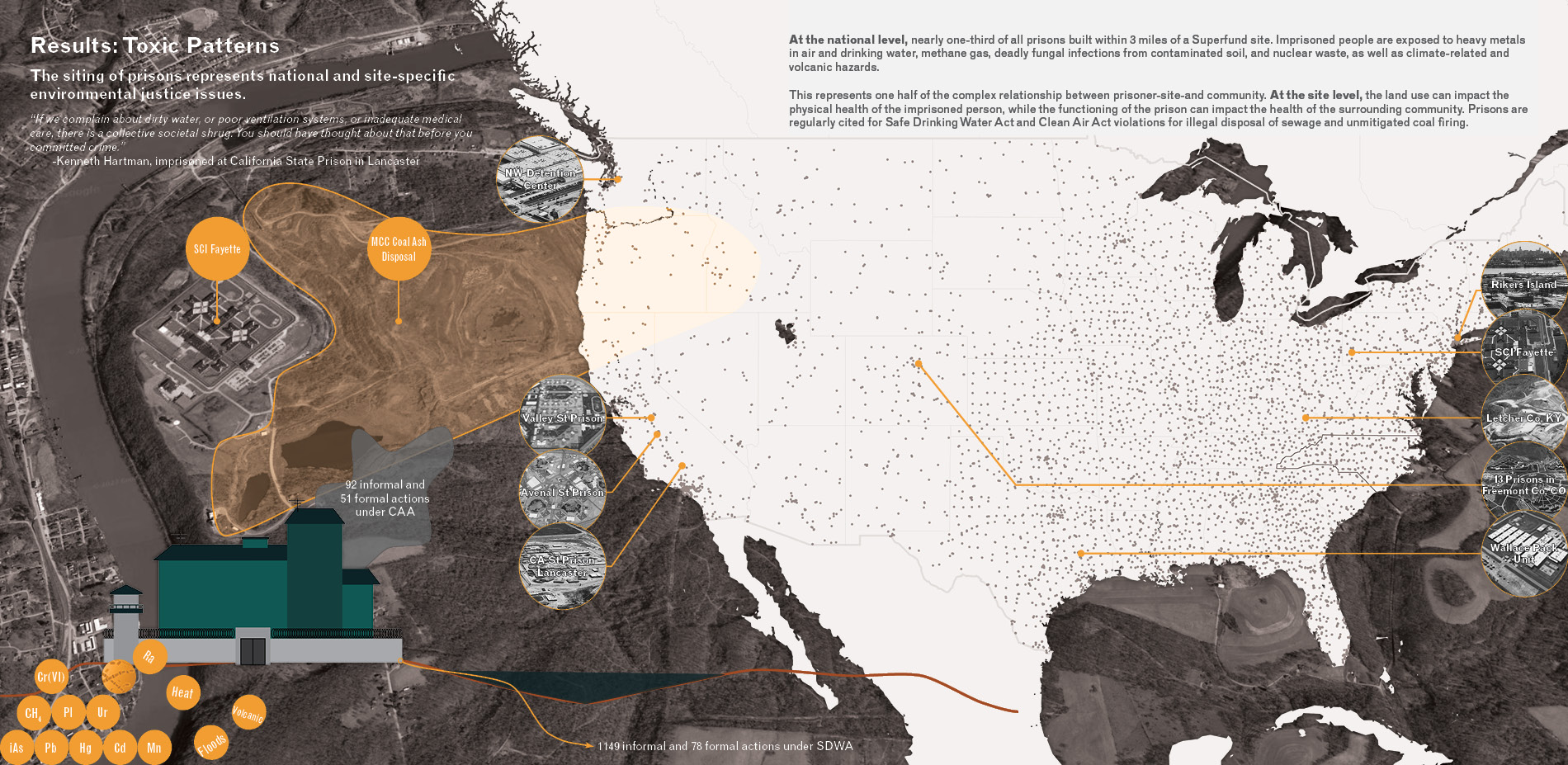

The results reveal that prisons are disproportionately located in rural areas. This is also validated by literature discussing the reasons and impacts of prisons in communities. Despite economic development promises, prisons show little positive impacts. Shifting prisoners from urban to rural areas fractures support systems of incarcerated individuals and perpetuates geographic theories of waste and social refuse. Nearly one-third of prisons were built within 3 miles of a Superfund site. They are sources of pollution receiving citations due to Safe Drinking Water Act and Clean Air Act violations. Finally, the design of prison sites represents interruptions to vegetative cover and present challenges to wildlife.

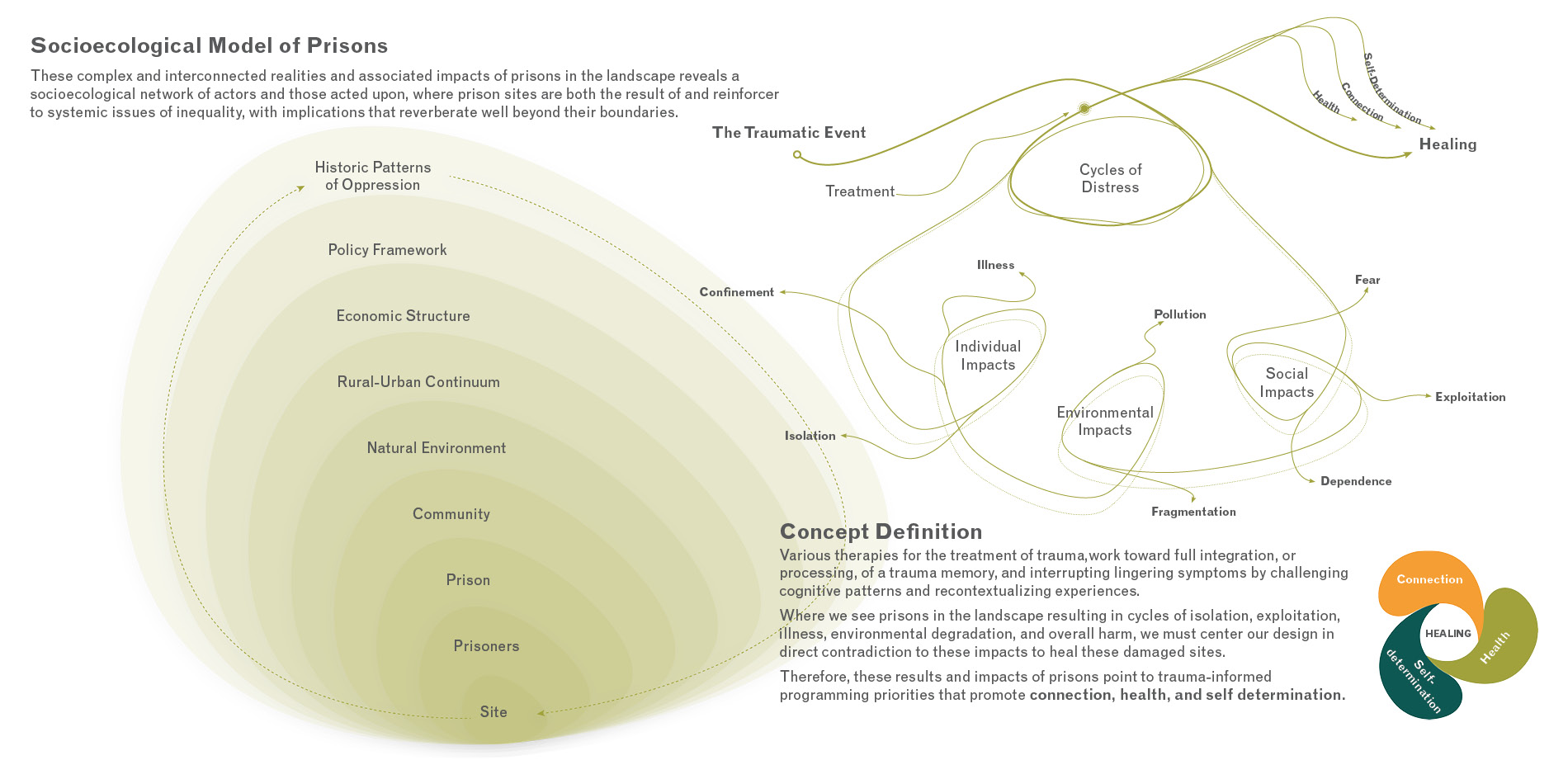

These complex realities reveal a socioecological network of actors and those acted upon. Prison sites are both the result of and reinforcer to systemic inequality, with implications that reverberate beyond their boundaries. These impacts can be felt at the individual, social, and environmental scales, and require treatment through design mitigating the negative results. The results point to trauma-informed programming priorities that promote connection, health, and self-determination. While this project applies this framework to a prison site in North Carolina, these priorities can also inform the redevelopment of other types of traumatized sites. This framework for developing trauma-informed site programming fills an important gap in the design process. If landscape is a palimpsest, it is our responsibility to peel back the layers, revealing how the land use decisions may impact and persist through time.