Boston Anthro-zoo Park: Redefining Zoos as Biophilic Public Spaces

Honor Award

General Design

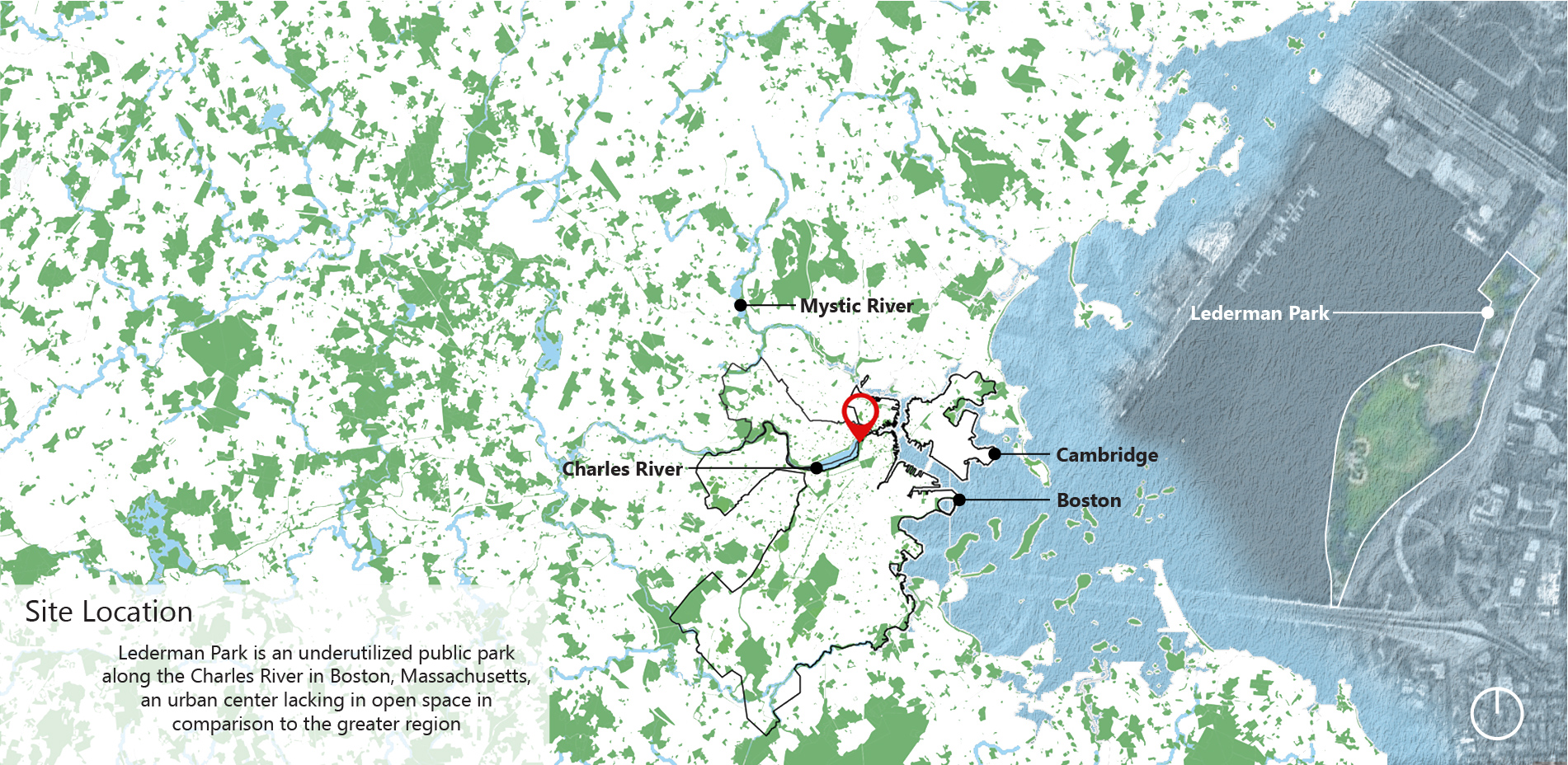

Boston, Massachusetts, United States

Andrew Carrano, Student ASLA;

Faculty Advisors:

Carolina Aragón, ASLA;

Theodore Eisenman, ASLA;

University of Massachusetts Amherst (BSLA)

The way this project balances the complex needs of the diverse animal population with Boston's human visitors is inspirational.

- 2022 Awards Jury

Project Statement

Urbanization has resulted in vast alteration of Earth’s ecosystems and in the exclusion of nature from the human experience. As we expand our cities and build new ones, people are further immersed in the built environment and detached from the lives of wildlife that once inhabited the lands that we have developed. Boston Anthro-zoo Park (BAZP) is a new model of zoo that is meant to enhance the native wildlife diversity of Boston and reconnect urban people with nature through storytelling and passive experiences with native wildlife. The modern zoo serves as a public institution that aims to entertain and educate the public while contributing efforts and funding to global conservation projects. BAZP builds on these goals by implementing site scale urban rewilding strategies to attract free ranging native wildlife and provide a space where people can experience true nature without leaving the city.

Project Narrative

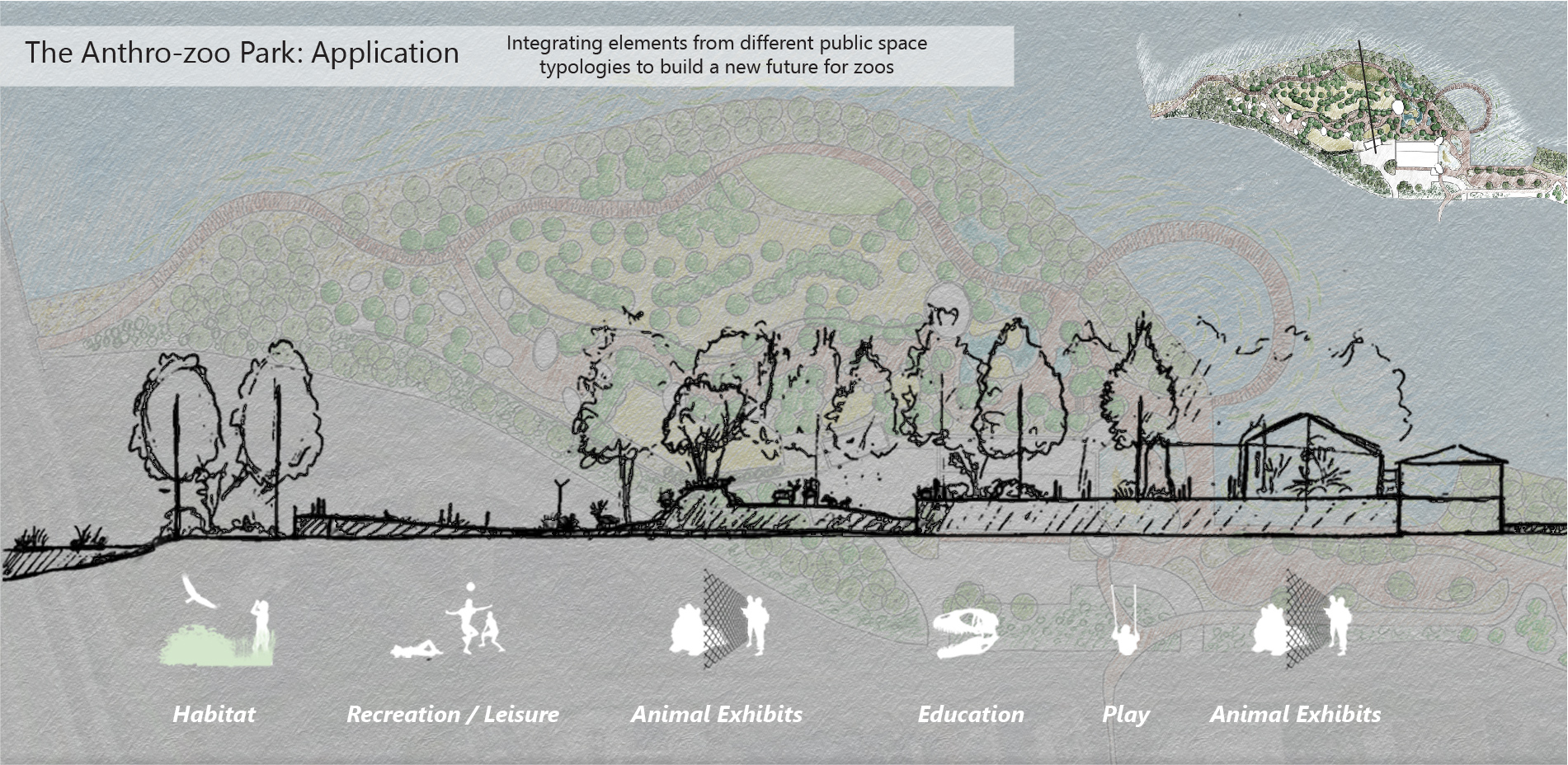

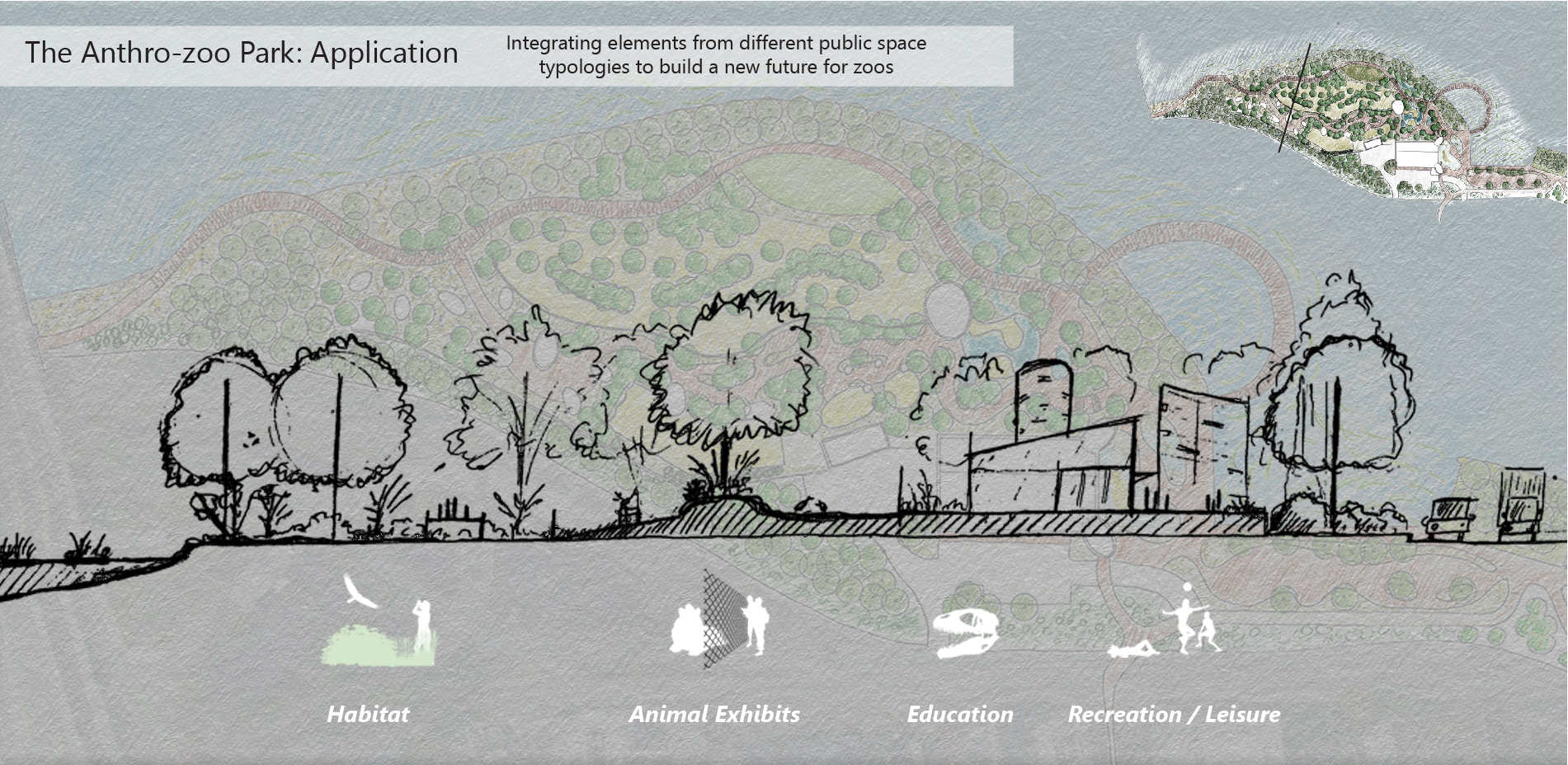

Proposed Program

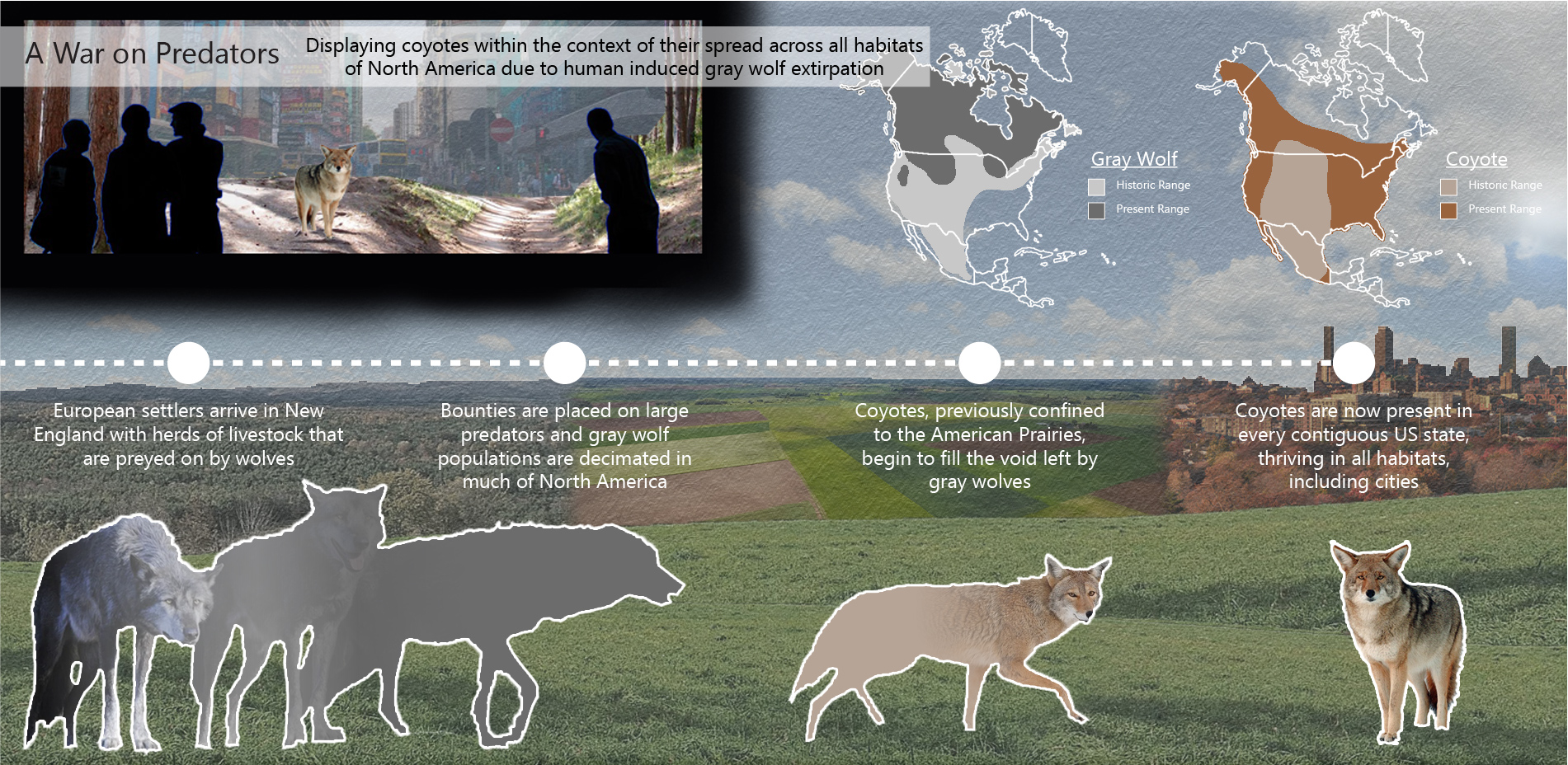

Boston Anthro-zoo Park (BAZP) is designed to reconnect urban people with the ecosystems that previously existed and currently exist in and around Boston. This project integrates functional wildlife habitat, public leisure space, interactive playscapes and interpretive displays into the conventional zoo exhibit model. Using the site and its context for inspiration, a narrative is built and conveyed showing the human-animal interactions throughout Boston's development. By presenting wildlife through different stages of Boston’s development, users are taught how specific alterations to the environment have affected ecosystems. This form of presentation exposes users to topics in ecology using a familiar environment to enhance understanding of the ideas presented. The goal of this narrative is to teach users how humans have altered specific environments, how those changes have affected ecosystems and how we can continue to alter our environment in a way that benefits wildlife.

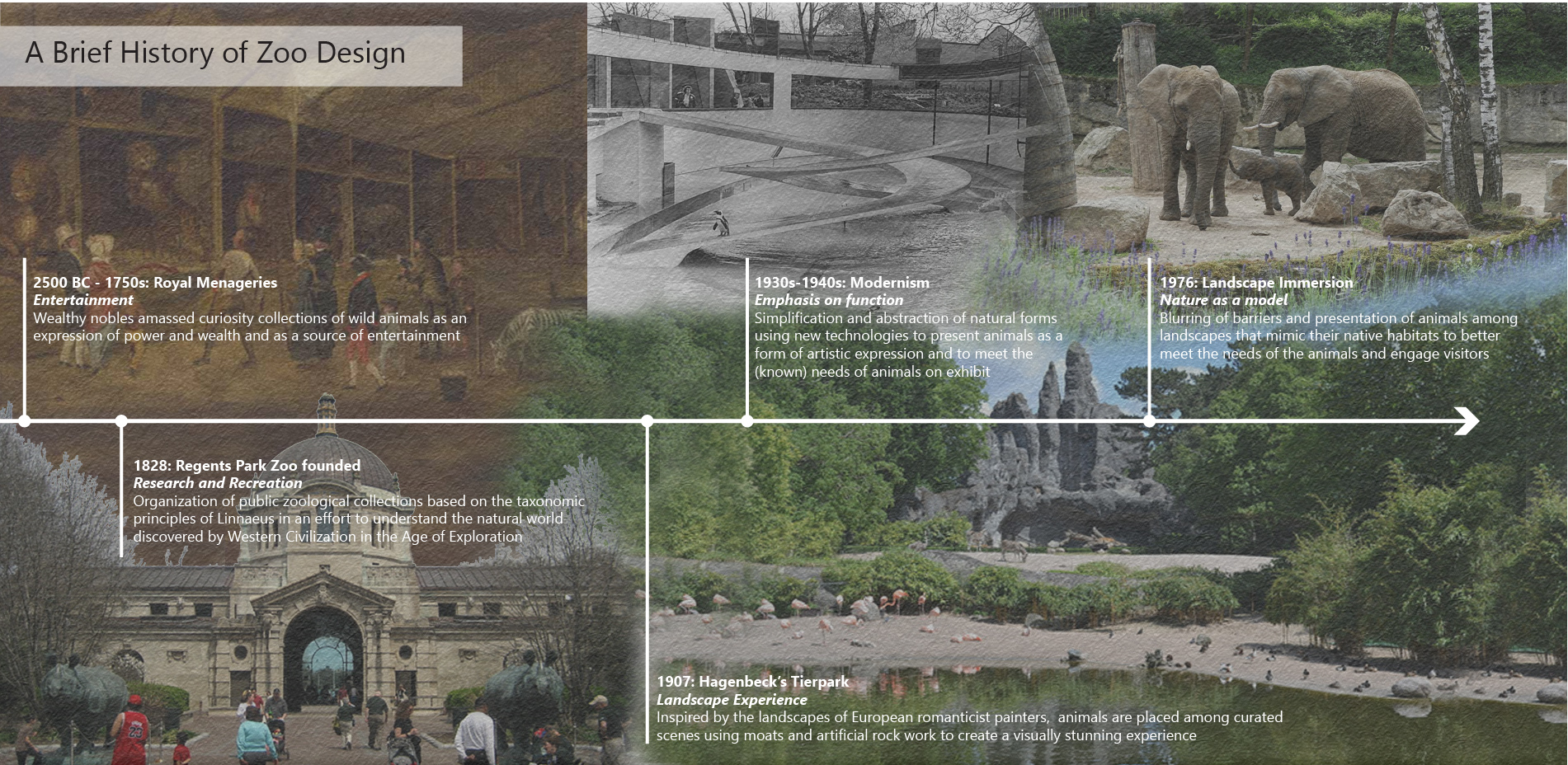

A Brief History of Zoos

The function of zoos has drastically evolved since their conception based on cultural trends. Zoos began as early as 2500 BC as royal menageries: decorative gardens filled with exotic animals, kept for their aesthetic value and expression of wealth. Some examples are the zoological collections of the 1700s at the palaces of Versailles and Schonbrunn. Zoos soon evolved into public, research oriented institutions. The Regents Park Zoo opened to the public in 1828, showcasing exotic animals organized in taxonomic groupings to facilitate research in the latest trend in natural science, classification through comparative physiology. Romanticism was a driving force in the evolution of zoos into experiential landscapes. In 1907, Carl Hagenebck built Tierpark, a zoo that placed animals among a curated landscape using artificial rockwork and moated exhibits to control sight lines and create grand visual scenes. The influence of modernism in the 1930s and 1940s is marked by the simplification and abstraction of natural forms to streamline zoo exhibits into functional, sculptural pieces. The Penguin Pool at the London Zoo was designed to meet the needs of its inhabitants using the simplest possible forms, but was ultimately a failure as the needs of penguins were assumed rather than known. The environmentalist movement of the 1970s inspired a movement in zoo design towards using nature as a model, dubbed landscape immersion. A forerunner of landscape immersion is CLR’s “Long Range Physical Development Plan” for the Woodland Park Zoo in 1976. This plan curates the visitor experience by visually softening barriers between people and animals and uses natural ecosystems as a model for animal habitat design. This design approach is based on the idea that emotional responses to an experience enhance retention of presented ideas and that presenting animals in their natural context is best for animal welfare and imbues a greater respect and appreciation for the animals. The modern zoo focuses on animal welfare, education and conservation, showcasing exotic animals in immersive recreations of their natural habitats. BAZP aims to serve as a new model for the function of zoos in society; as a place to be with nature and understand the environment that one experiences daily.

Site Context

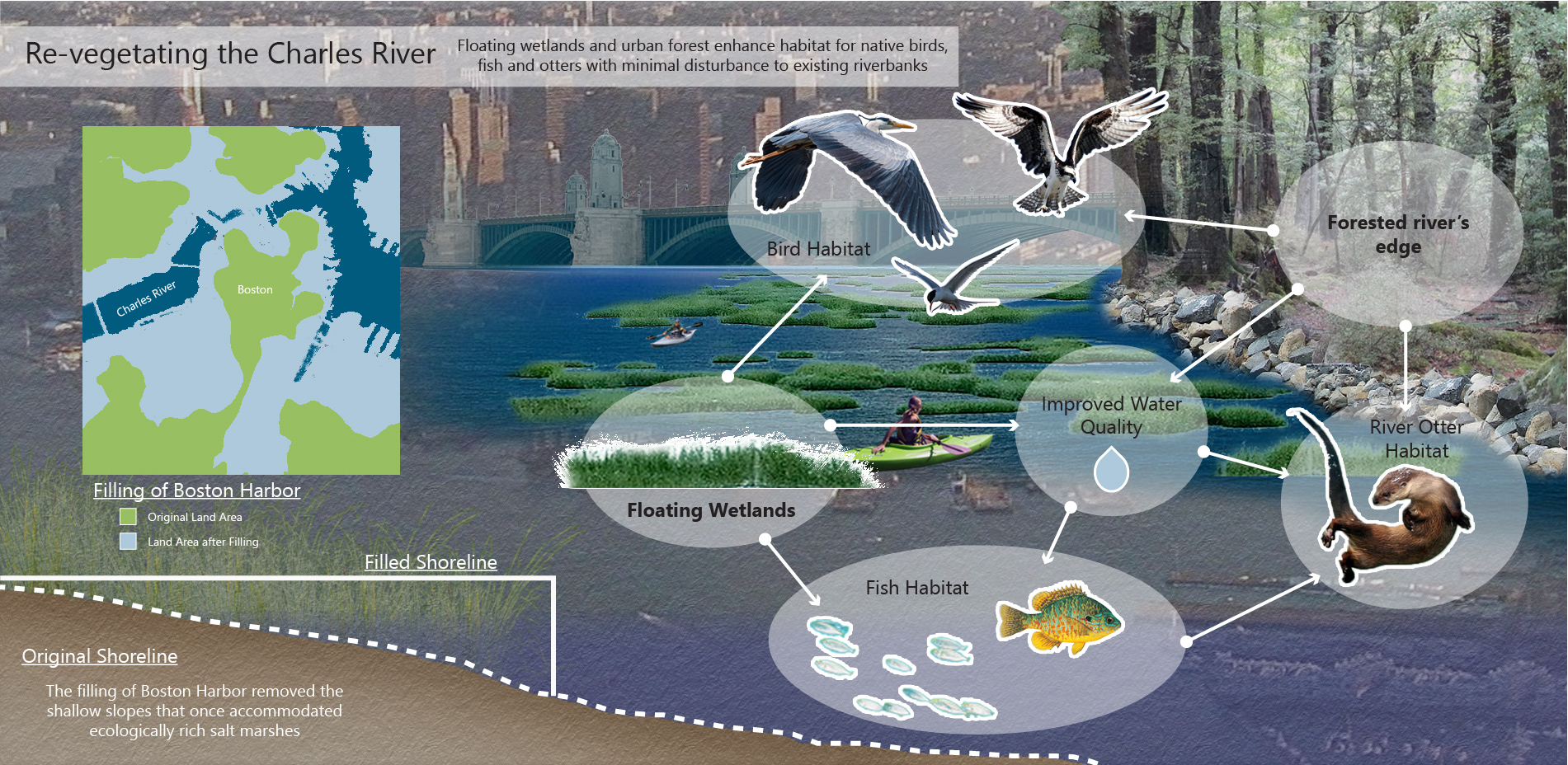

Lederman Park is a 13.6 acre public park situated at the north end of the Charles River esplanade. Currently serving as an athletic field complex, the site’s substrate consists wholly of turf grass and pavement. Its adjacency to the Charles River provides an opportunity to revegetate the urban waterway using floating wetlands. A formal alley and grove of primarily healthy, native trees lines the river’s edge. An adjacent series of major roadways largely separate the site from pedestrian circulation in the city and create constant noise that travels across the flat site.

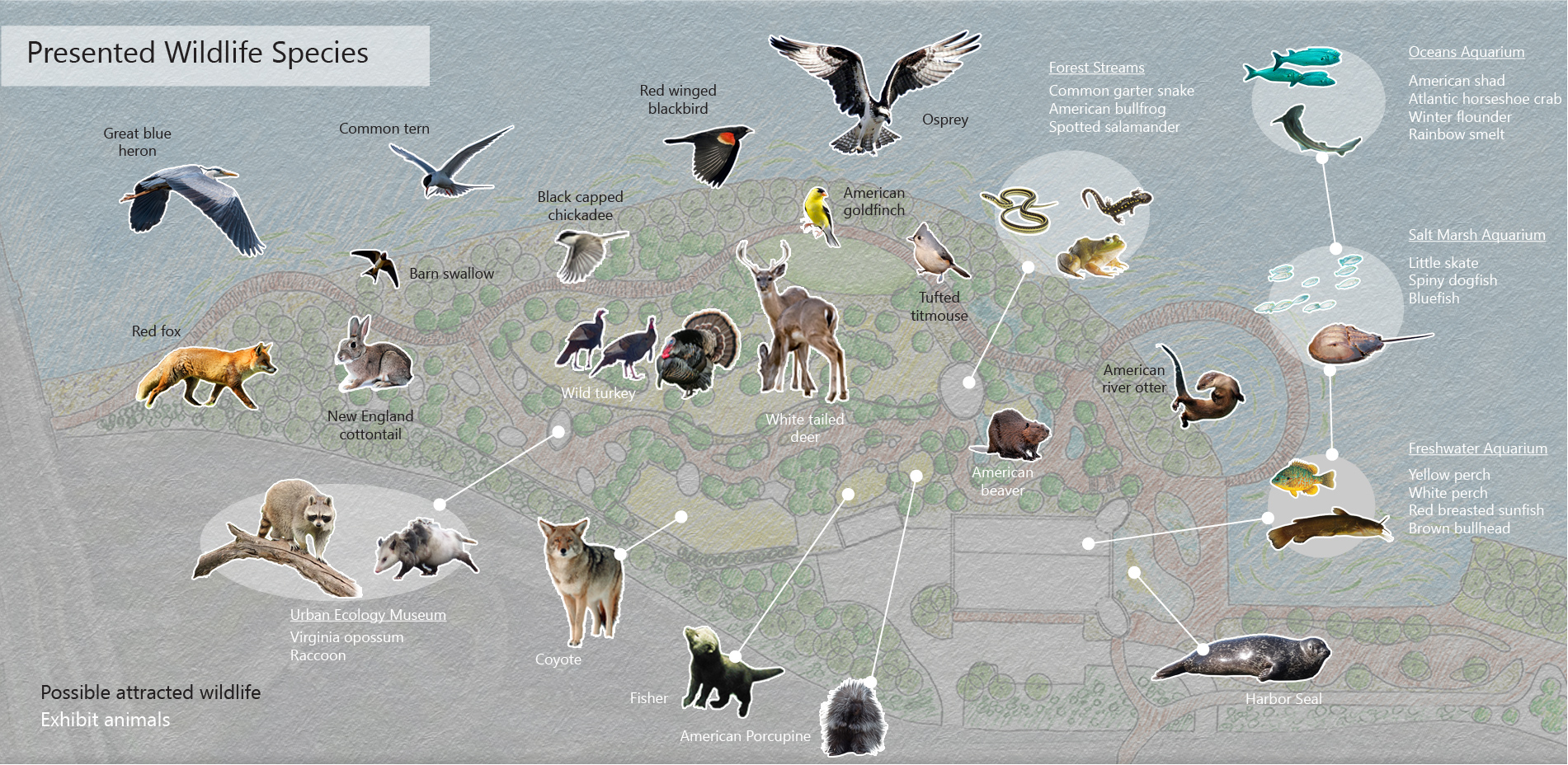

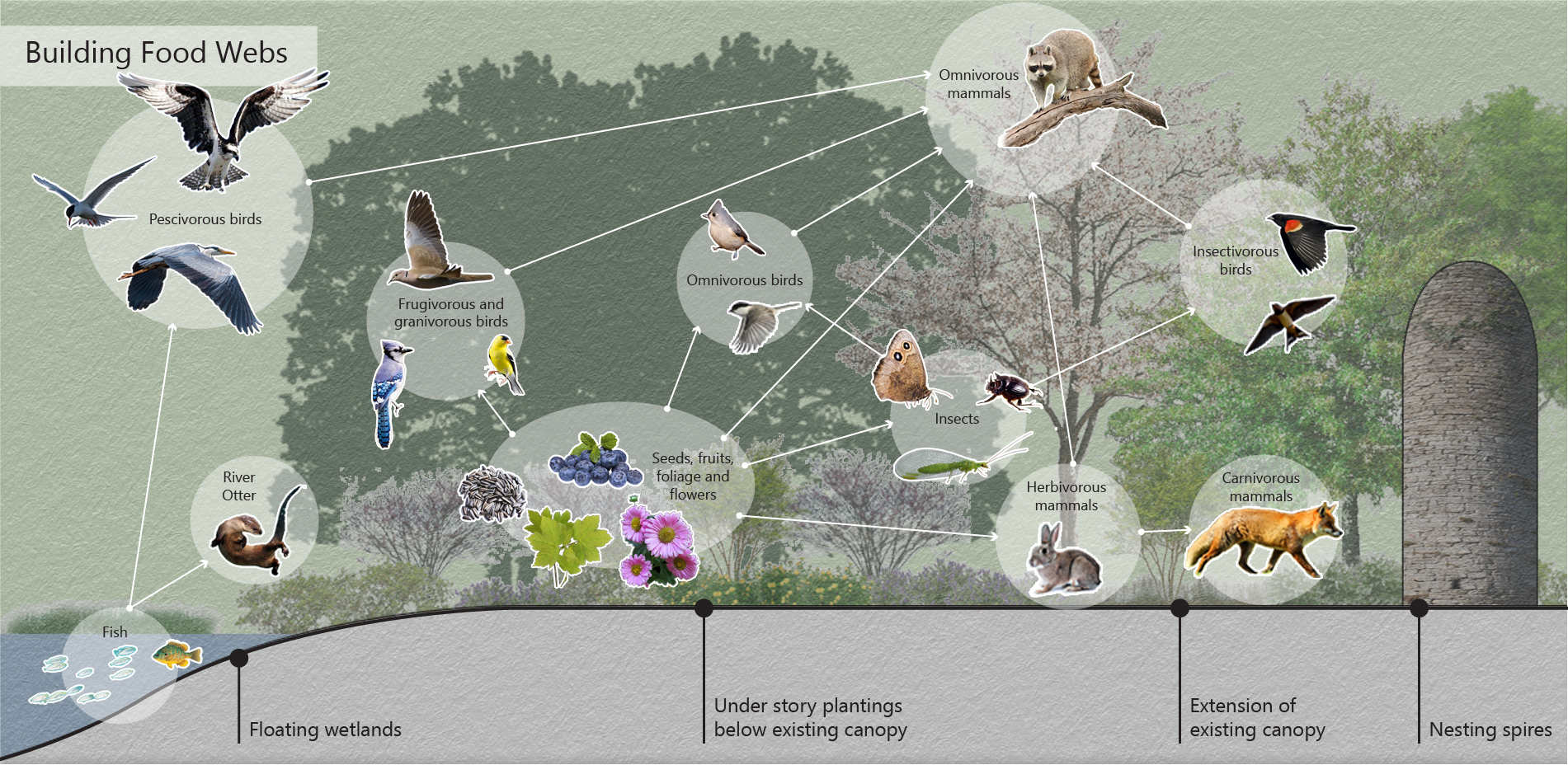

Habitat Restoration and Creation

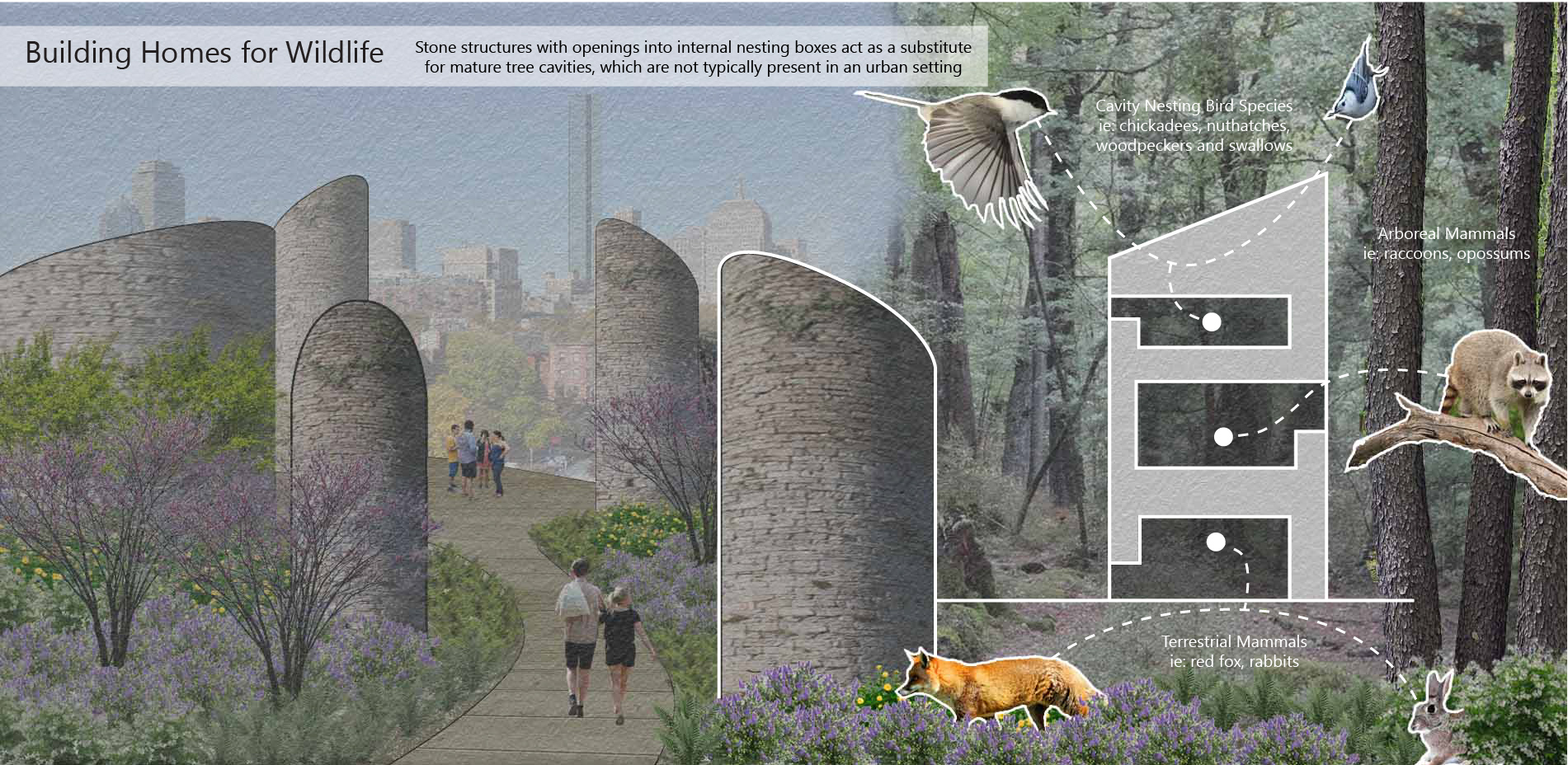

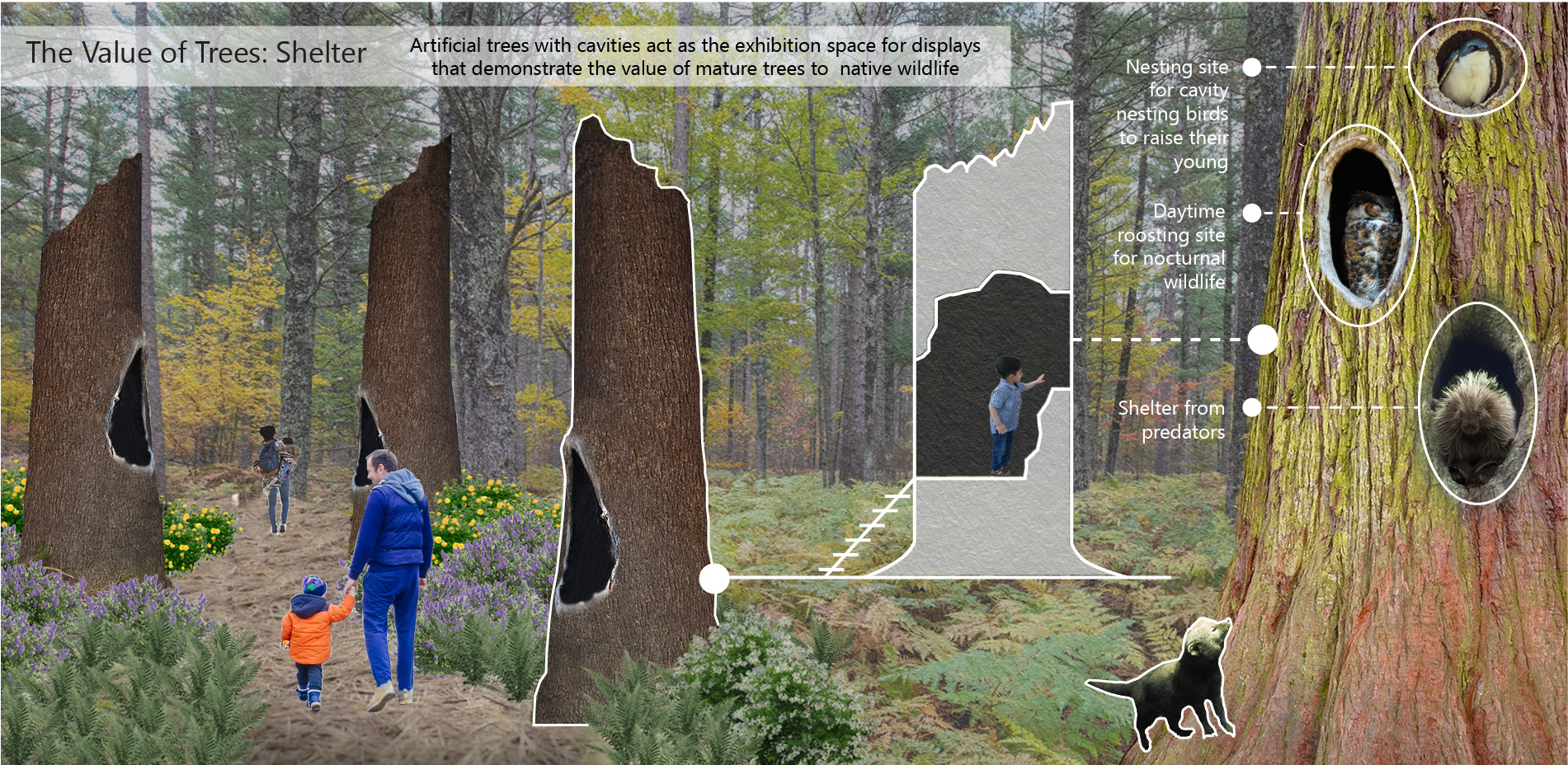

BAZP utilizes urban rewilding methods to immerse users in nature and demonstrate real world solutions that can be applied to urban open space to bolster native biodiversity. Ecological restoration of the site’s existing features aims to enhance the habitat quality for native species. Floating wetlands placed along the river’s edge improve water quality and provide cover for aquatic wildlife and food sources for birds and American river otters. Existing canopy is extended and filled in with a diverse understory of flowering and fruiting plant species to provide food sources and cover for native bird species in all seasons. Nesting spires provide denning and nesting space for wildlife seeking cover, acting as a substitute for cavities found in old growth trees that are not typical of urban environments.

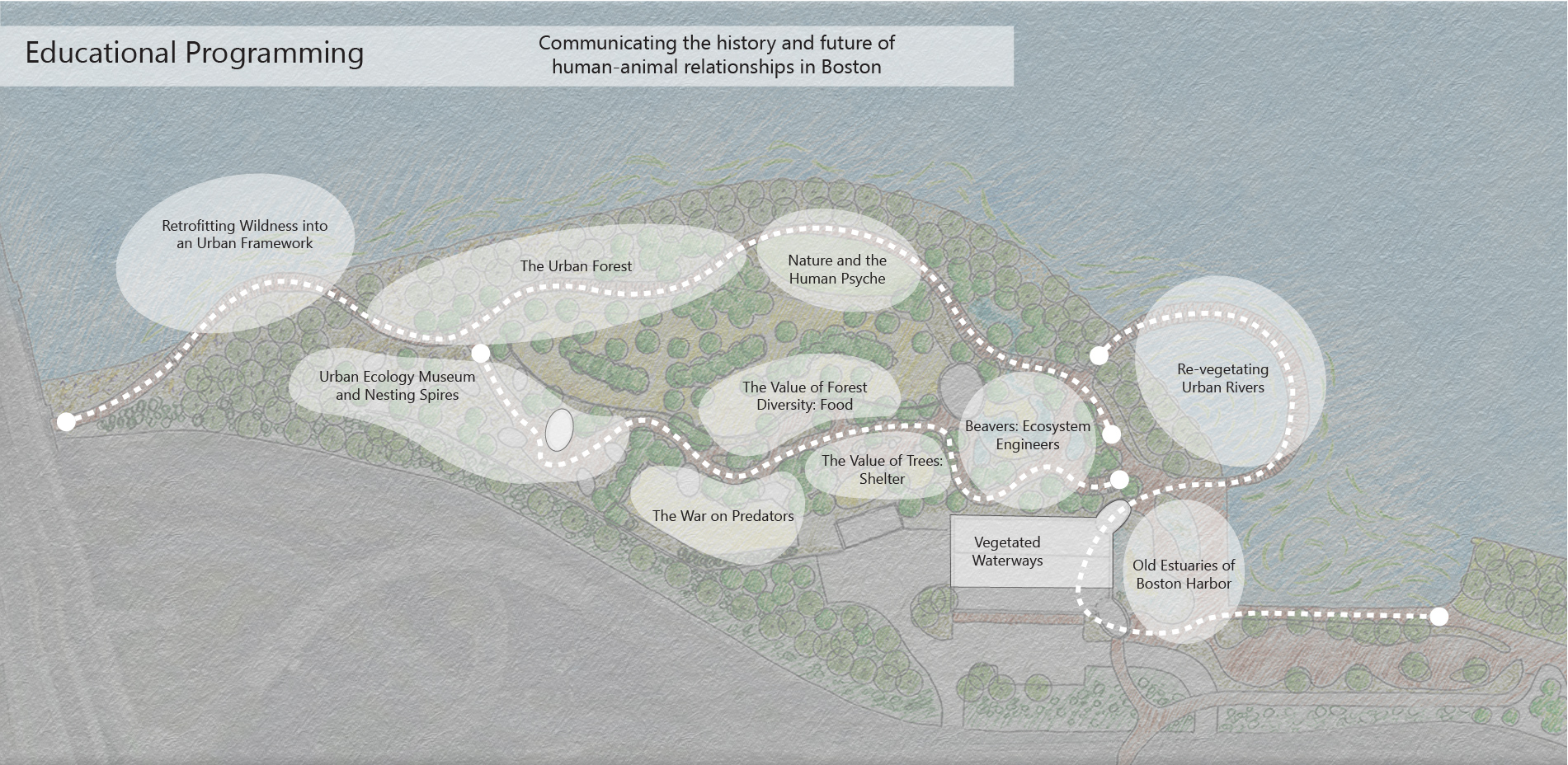

Communicating Human Animal Relationships

BAZP is designed using an educational narrative as its framework. Concepts in ecology are communicated using stories of human-animal relationships throughout the history of Boston’s development to demonstrate how human alteration of the environment can alter ecosystems. One such example is the series of exhibits inspired by the history of Boston Harbor:

Before the expansion of its banks, Boston Harbor was an extensive salt marsh estuary, teeming with grasses, fish, birds and aquatic mammals, sustained by the nutrient rich interface of freshwater rivers and the sea. To make space for urban development, the gently sloping shores were filled in and became vertical seawalls incapable of hosting intertidal plant communities.

This is demonstrated by juxtaposing a lush salt marsh ecosystem inhabited by harbor seals with the unvegetated Charles River below the historic sea wall.

This led to a decrease in ecological productivity of the landscape and the relatively nature devoid Boston Harbor that we see today.

Using a pair of aquariums depicting a diverse salt marsh community and the current waters of Boston Harbor, the contrast in biological abundance between the two habitats is emphasized.

Vegetation in and along waterways is important for wildlife habitat value, nutrient flow and its function in preserving healthy water quality.

A series of three aquariums depicting freshwater, estuarine and saltwater ecosystems of Massachusetts demonstrate the interconnectivity of aquatic ecosystems and how vegetation bolsters their health and function.

Urban waterways, such as Boston Harbor and its associated rivers, are not beyond saving. The use of floating wetlands and forested shorelines along the banks of the Charles River can contribute to re-building a productive aquatic ecosystem.

A boardwalk reaches out into the Charles River, offering views of surrounding floating wetlands and the re-vegetated shoreline inhabited by native bird species (such as great blue heron, red winged blackbird and American goldfinch) and American river otters.

The Human Experience

Exposure to nature and biodiversity is known to improve human mental health and encourage a person’s participation in conservation projects. BAZP creates spaces where people can experience nature and wildlife through different modes of activity. A boardwalk 3’ above the ground winds through a restored forest along the shore and offers a running path through a landscape filled with the sounds of birds and a view of the Charles River. A sunny lawn space slopes down and overlooks a forested paddock of foraging white tailed deer and wild turkey, providing a space for a leisurely picnic. A series of wading pools and splash pads with unique patterns of water movement surround a beaver pond, allowing for people to experience the effects of beaver dams on hydrology patterns with beavers in view. By offering diverse mediums of viewing wildlife in a public setting, BAZP attracts a wider audience in an effort to rewild the urban human experience.

Works Cited

Coe, Jon C. 1986. “Towards a Co-evolution of Zoos, Aquariums and Natural History Museums” in AAZPA 1986 Annual Conference Proceedings, American Association of Zoological Parks and Aquariums, Wheeling, WV, pp. 19-23. Abstract

Coe, Jon C and Mendez, Ray, 2005. “The Unzoo Alternative” ,2005 ARAZPA Conference Proceedings, Australia, on CD. Abstract

Michael W. Strohbach, Susannah B. Lerman, Paige S. Warren, Are small greening areas enhancing bird diversity? Insights from community-driven greening projects in Boston, Landscape and Urban Planning, Volume 114, 2013, Pages 69-79, ISSN 0169-2046, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.02.007.