The Death and Life of Water: Improving Water Use in Jaipur, India

Honor Award

Residential Design

Jaipur, India

Chenjie Xiong

Faculty Advisors: María González Aranguren; Pankaj Vir Gupta

University of Virginia

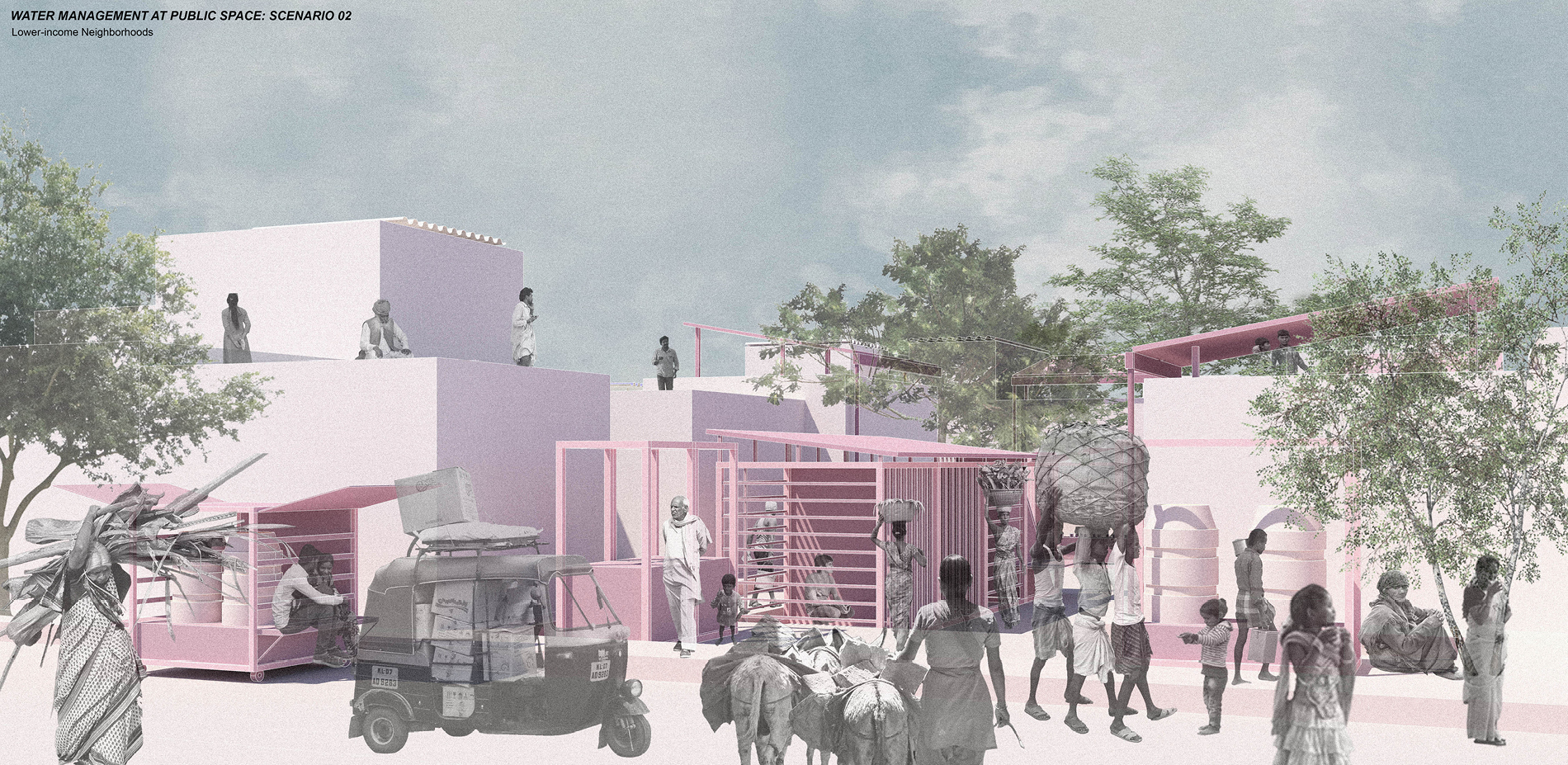

The jury appreciated how this project—which proposes new ways of managing residential water use in Jaipur, India—delved into the typology of systems and the way water is used in residential units, deploying new strategies with public space pavilions in addition to housing. The scenarios were tested, which added the extra benefit of seeing the systems improved. Overall it was clear, cohesive, attractive, and very site-specific.

- 2021 Awards Jury

Project Credits

Iñaki Alday

Co-Director of the Yamuna River Project, Dean and Koch Chair, Tulane School of Architecture

Darcy Engle

Yamuna River Project Research Fellow

Project Statement

People in the city of Jaipur, India have always been struggling with water scarcity during dry seasons and inundation during monsoon seasons throughout history due to the semi-arid climate and improper water use.

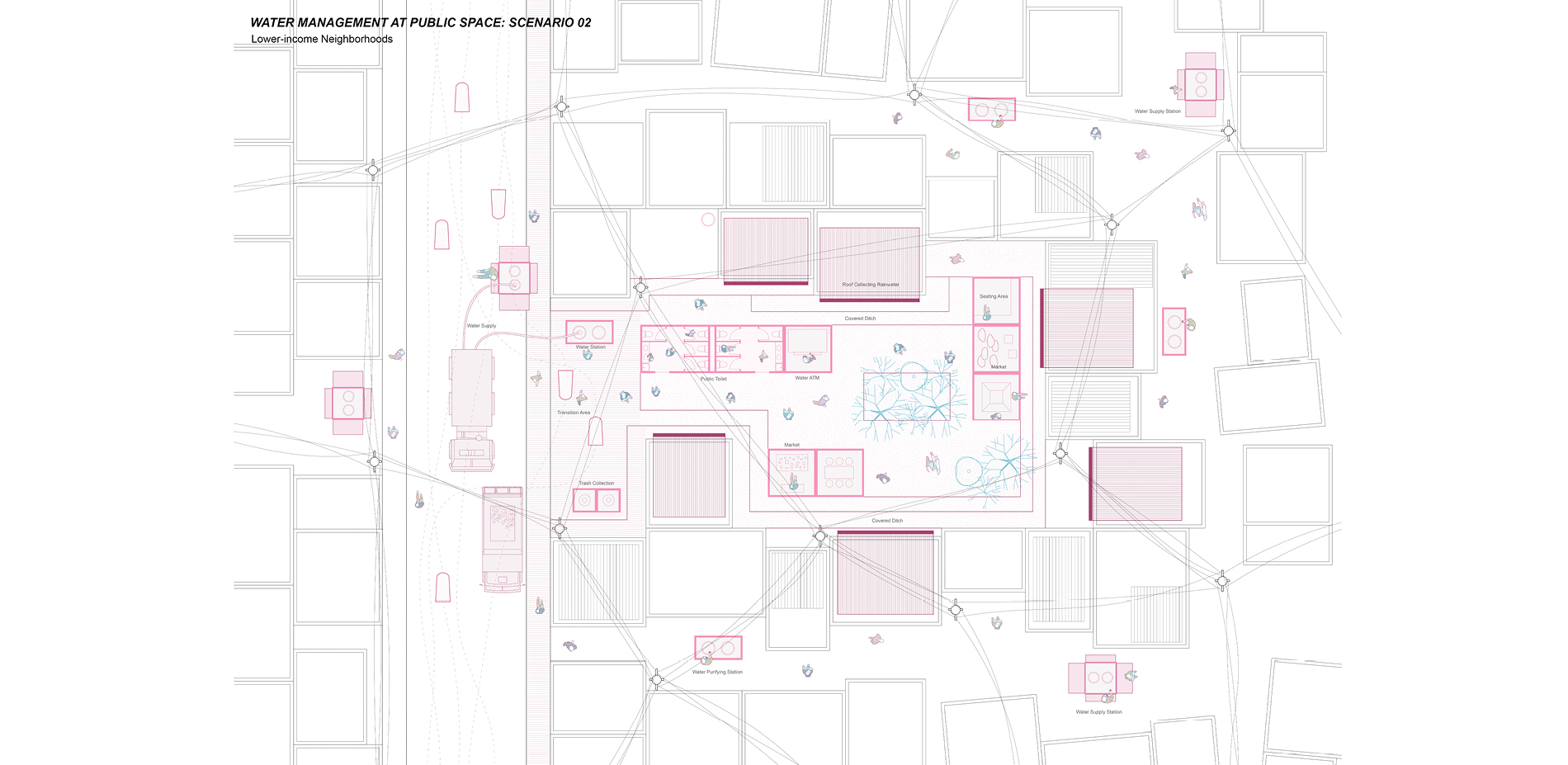

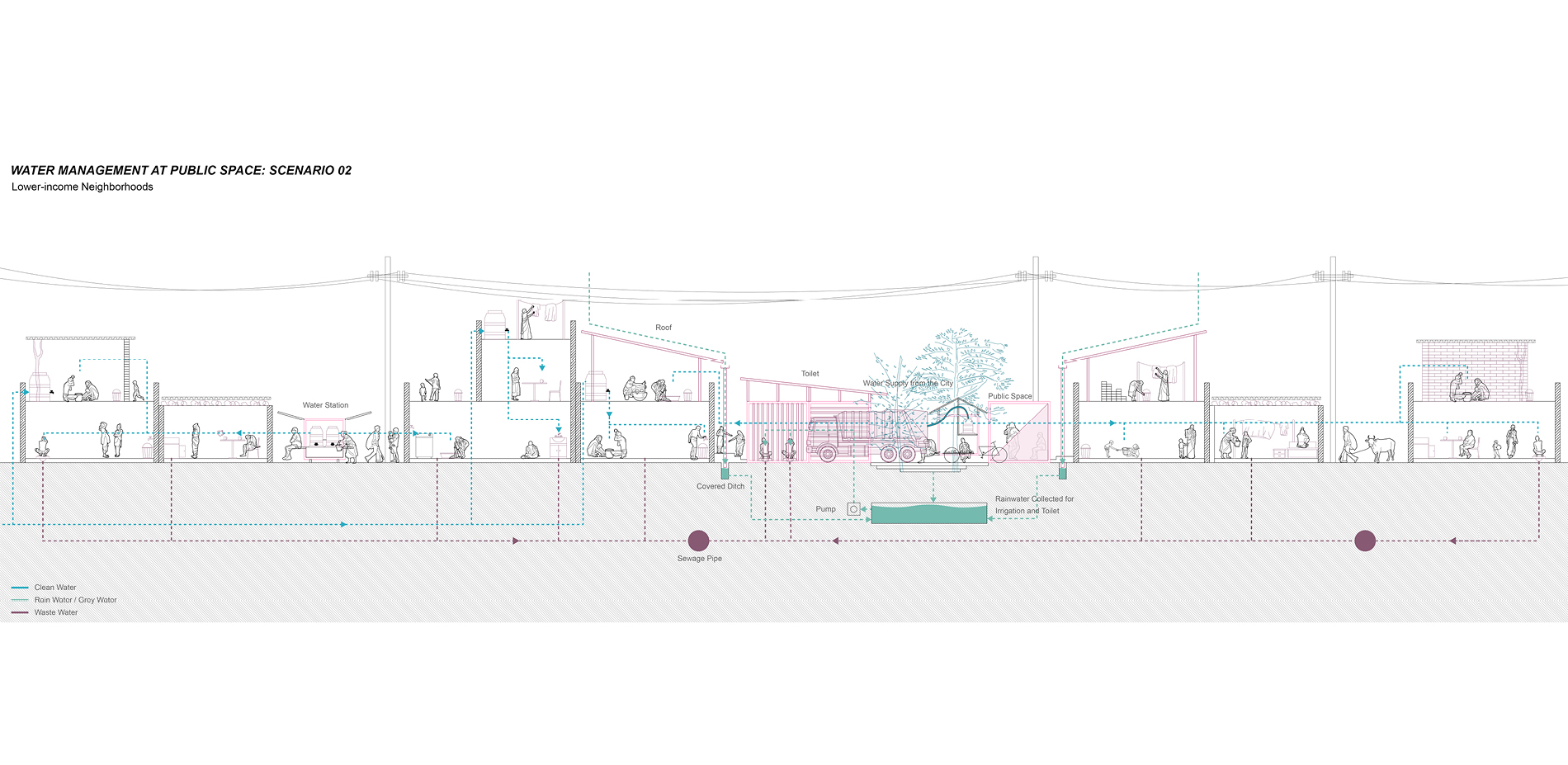

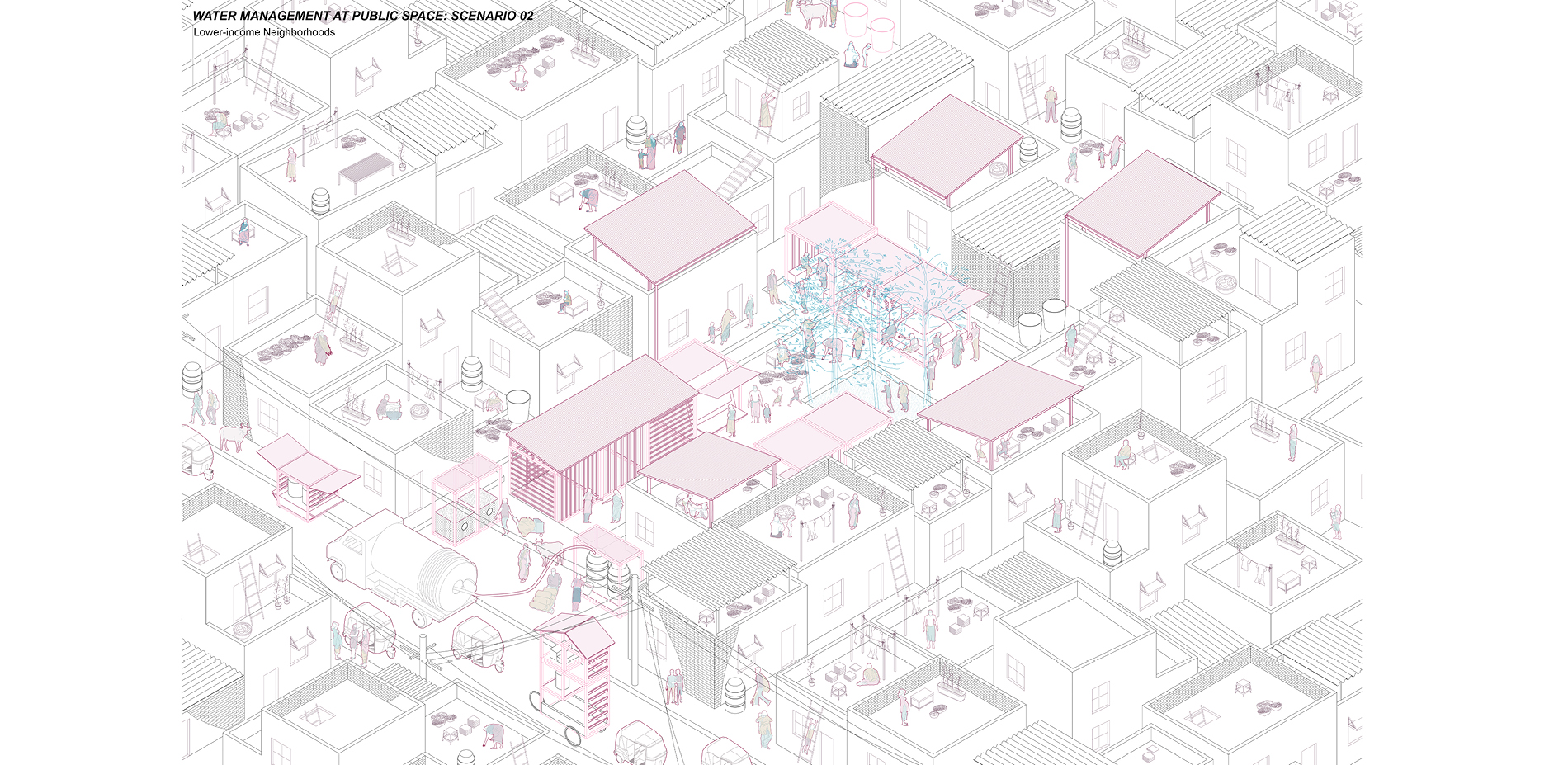

Based on investigations on the current water use at housing, community and urban scale, the project envisions an alternative way to manage the whole water lifecycle including water supply, water consumption, water disposal and water harvesting, by the design of various water infrastructures. These water strategies are combined with public spaces in the community, providing better quality of public spaces while giving visibility to the water process.

Two prototypical scenarios of communities with different income levels were tested by various strategies. This system could become a set of toolkits that could be applied to other places as well.

Through the implementation, in a higher-income neighborhood with 100 households, 56% of the public toilet flushing water could be from the collected rainwater; in a lower-income neighborhood with 80 households, 22% of the public toilet flushing water could be from the collected rainwater.

Project Narrative

ISSUES

The project was dealing with the water issues in Jaipur, India, researching on the possibility of altering water use by creating a system of water infrastructure and management in housing and public space.

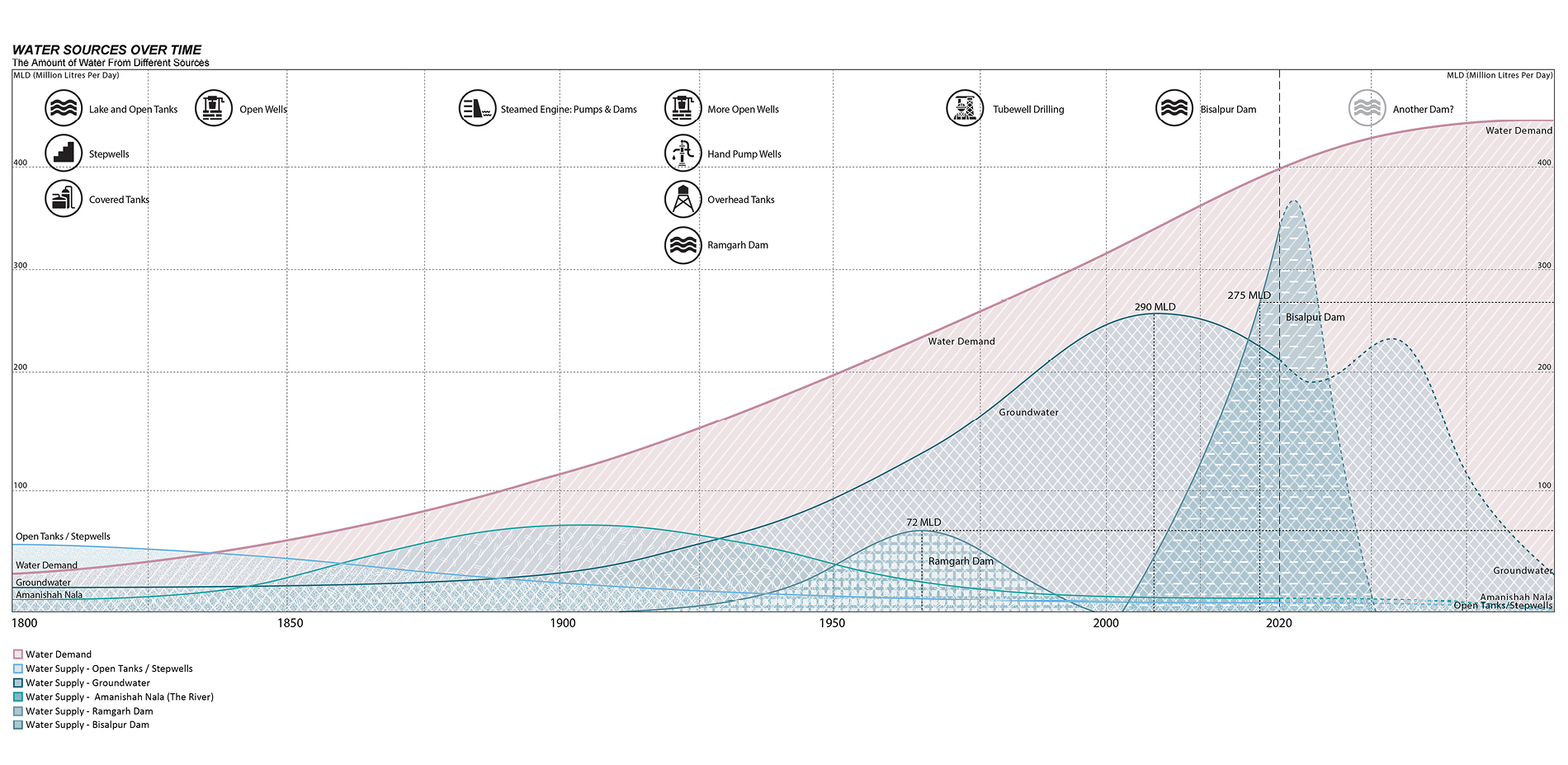

People in Jaipur have been struggling with water scarcity during dry seasons and inundation during monsoon seasons throughout history due to the semi-arid climate and improper water uses. Since the early 20th century, local water sources including waterbodies and wells have started becoming no longer accessible due to the excessive extraction. After exhausting the Ramgarh Dam 30km away from the city in 1990, Jaipur is currently heavily relying on the Bisalpur Dam, 150km away from the city. However, there are 20% of total water demands which still cannot be met, and it is projected that the city will lose this water source in less than 20 years. Additionally, the city is confronting flood issues as well; improper and informal drainage system and sewage system result in the city being filled with a mixture of rainwater, wastewater and trash during monsoon seasons.

RESEARCH

At first, the project conducted a comprehensive research on the current water use in Jaipur and India.

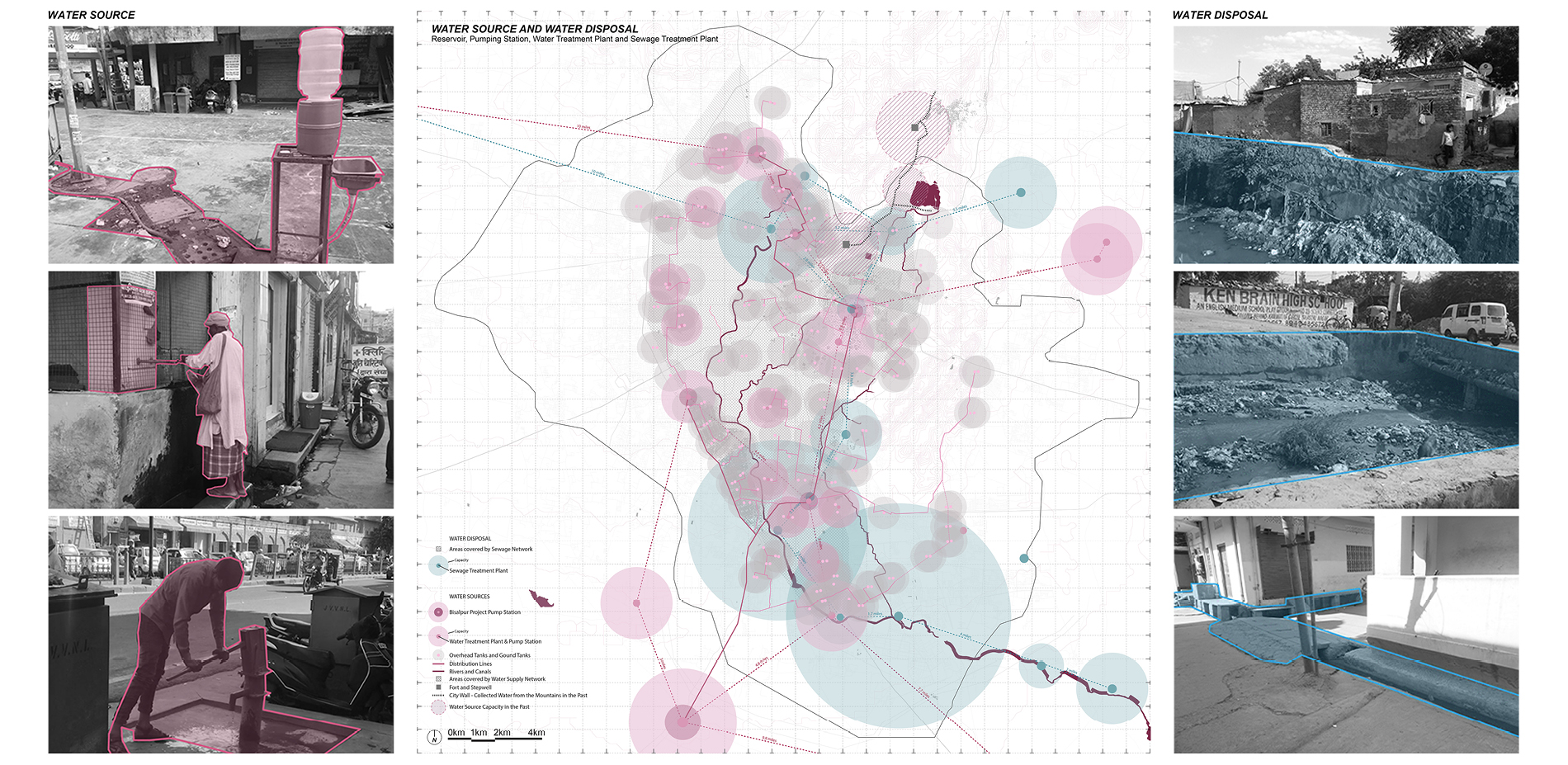

At the city scale, normally the fresh water comes from water treatment plant and goes to people’s homes, and then waste water goes to the sewage treatment plant. But there are also some informal water uses: many people cannot get treated water, so they have to obtain the unsafe water from water tanks on the streets, resulting in various diseases. Also, a lot of water is disposed directly into the river or even to the street without any treatment.

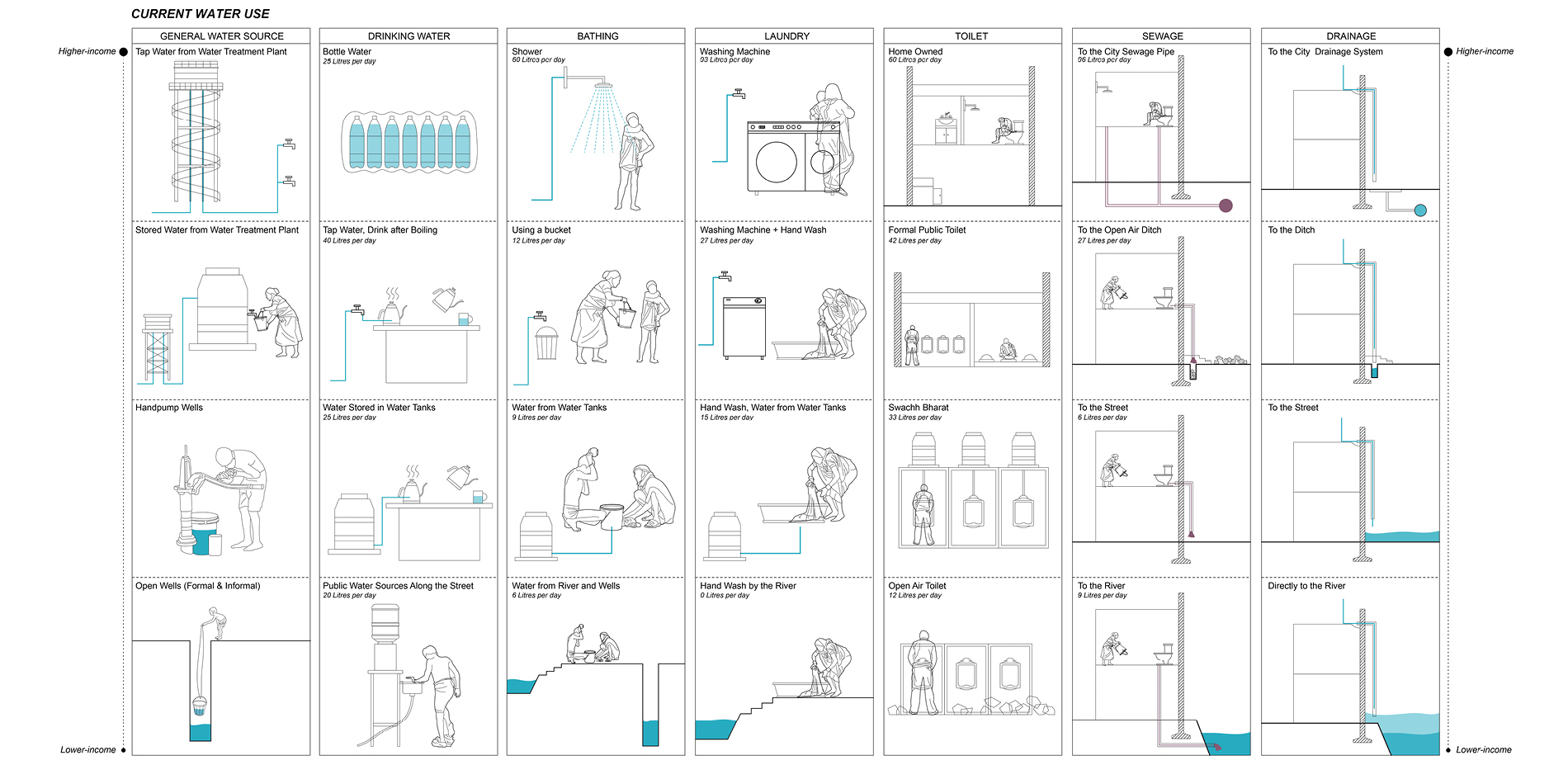

People with different incomes usually have different activities relating to water and different ways of using water in their homes.

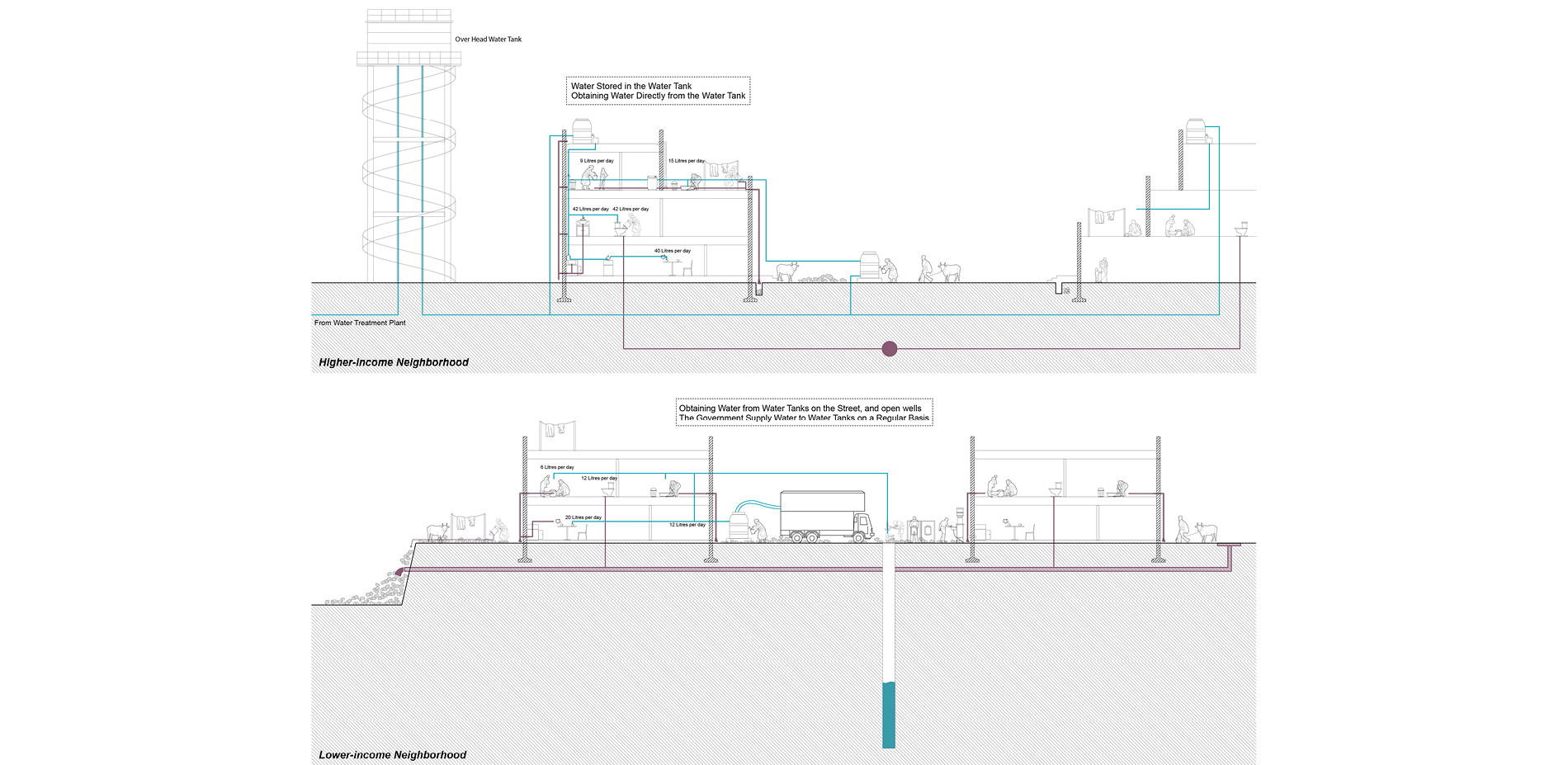

High-income families usually have direct access to treated tap water from the city. They can afford the safe bottled drinking water, and they use washing machine and have private toilet in their house. Their houses are normally connected to the closed urban sewage system.

Middle-income families usually have water tanks on the roof that obtain water from the city and those water tanks provide families with water directly. They may or may not be connected to the sewage system.

Low-income families mostly do not have access to treated water. They obtain the water from public water tanks on the streets. The government delivers water to those water tanks on a regular basis. Some water tanks are run by private parties so people have to pay for that. They also do not have public toilets. Waste water is discharged directly to the ditches, rivers, or streets.

INTERVENTION

In response to these serious water issues, this project envisions alternative solutions to manage the complete water lifecycle by the design of water infrastructures that meanwhile create better quality of public spaces. The project tries to develop a more sustainable way to help people live with water.

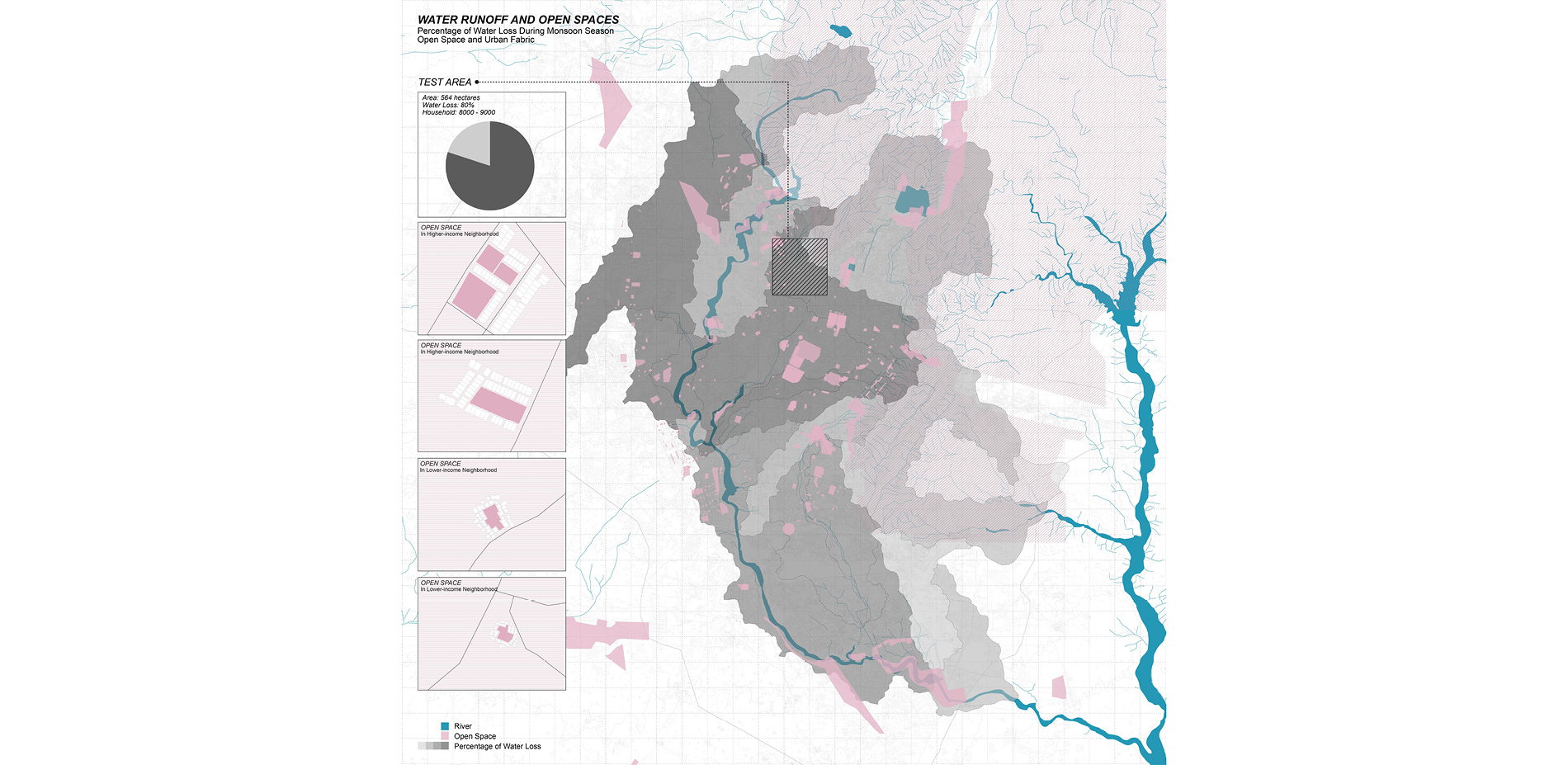

The test area has around 9000 households and around 80% water loss during monsoon seasons because of impervious surfaces. 48% of households do not have access to treated water; 83% of households are not connected to the closed drainage system.

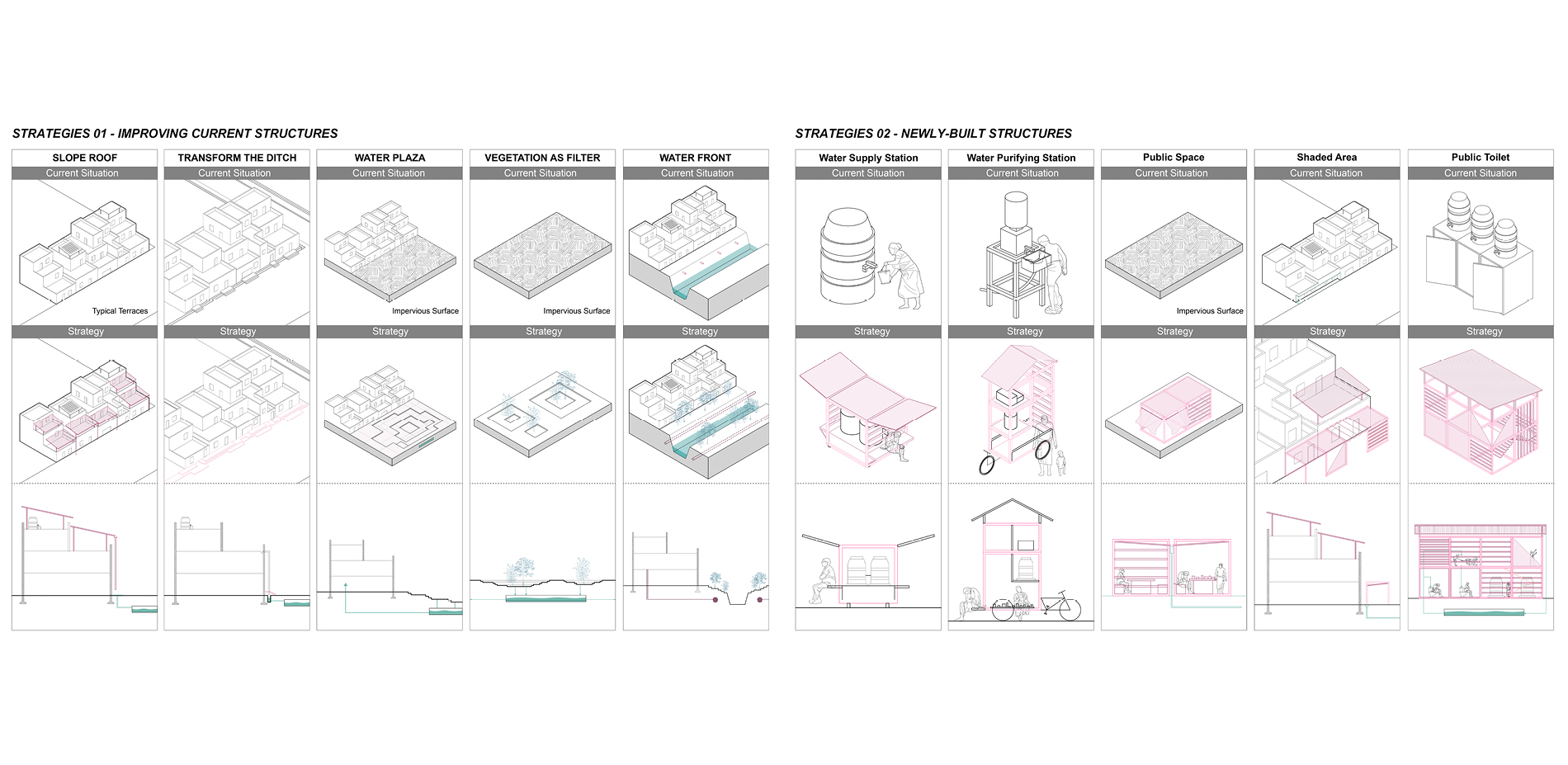

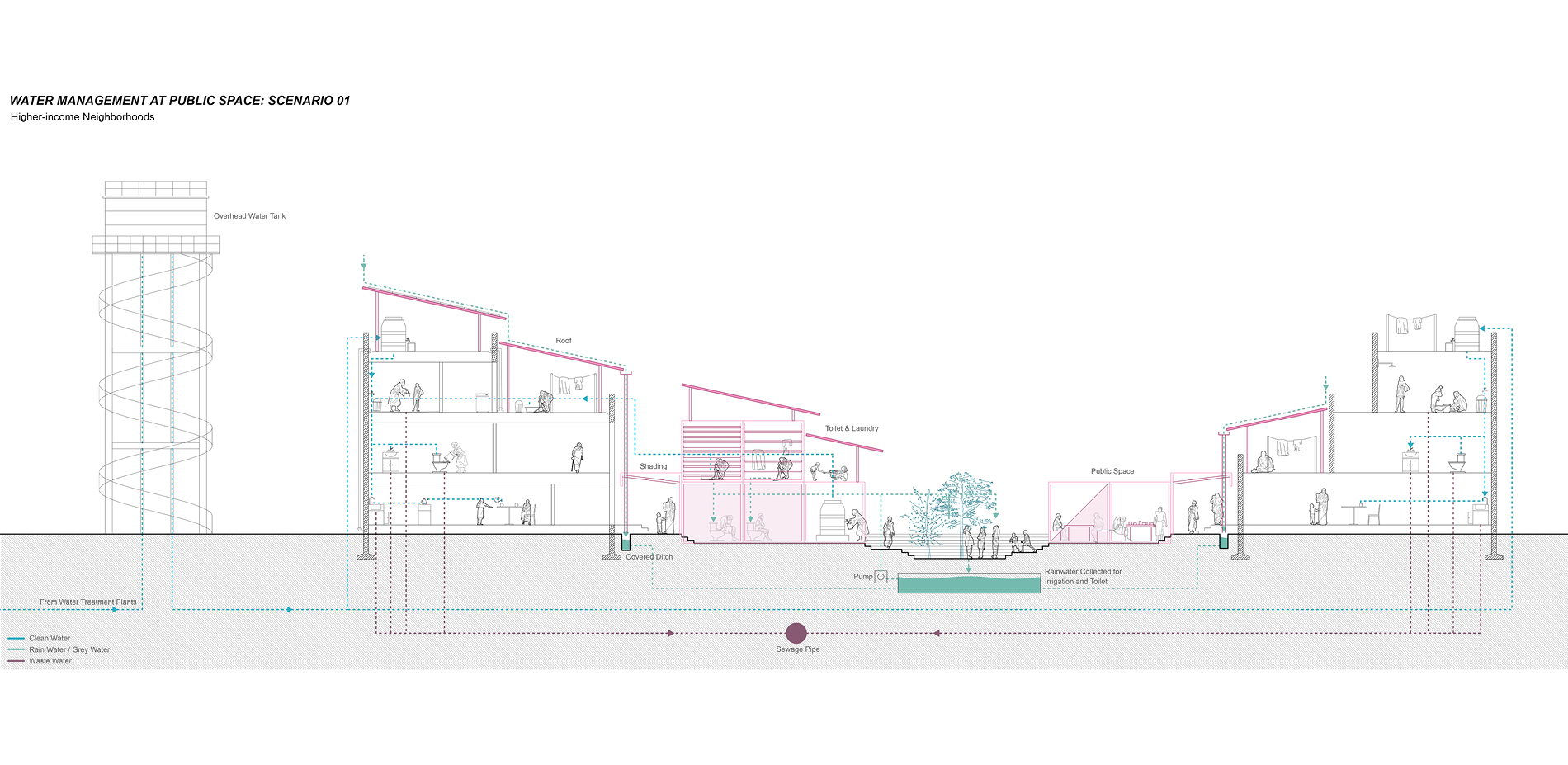

The intervention starts with proposing a system of water supply and disposal network in order to connect households to the city water network, while collected rainwater is stored locally in the neighborhoods and serves only nearby public toilets as gray water.

Then, a series of strategies for water management including improving current structures and building new structures are proposed, and these strategies could become a set of toolkits and prototypes that could be applied to multiple places. The whole water lifecycle - fresh water, domestic water use, waste water, and rainwater – are all considered. Prefabricated, light modular structures are inexpensive and easy to be installed at open spaces, and their dimensions are flexible according to different types of public spaces accommodating commercial and recreational activities. Potential programs of public spaces include shading area, market, handicraft studio, water supply station, water purifying station and public toilet, integrating daily activities with water use and sanitation management.

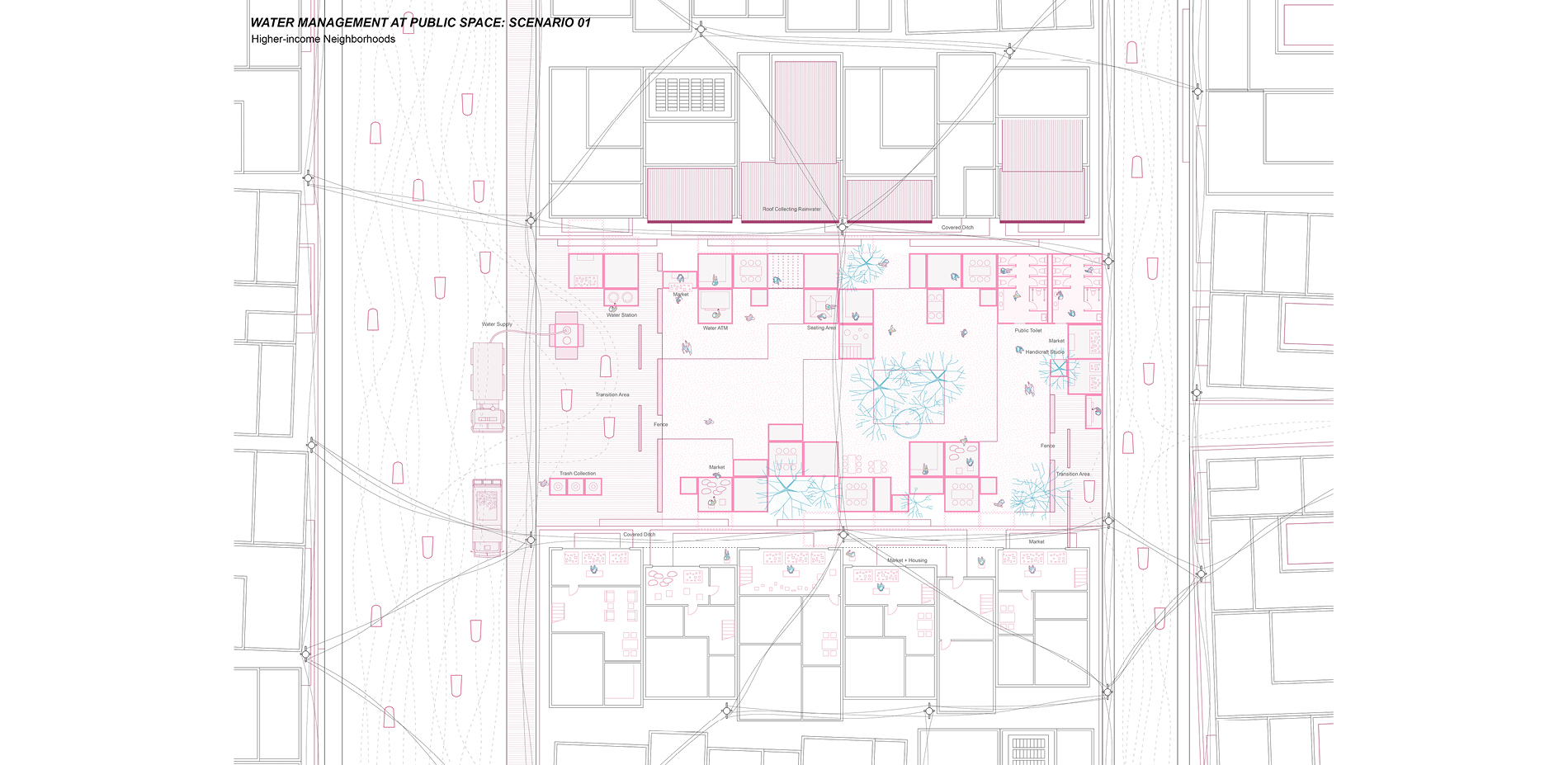

After that, two prototypical scenarios of neighborhoods with different income levels are tested by selecting certain strategies from the strategy toolkits based on the existing contexts of the neighborhoods. The two neighborhoods with different income level may have different focus: basic water infrastructure is of more importance in the low-income neighborhood, whereas an integration water management and great public spaces is more needed in the medium-income neighborhoods. After building this prototypical water system on the test sites, it could be replicated in other areas based on their contexts in order to further expand the system.

Through the implementation, in a higher-income neighborhood with 100 households, 56% of the public toilet flushing water could be from the collected rainwater; in a lower-income neighborhood with 80 households, 22% of the public toilet flushing water could be from the collected rainwater.