Dam(m/n)ed Earth

Honor Award

General Design

Owens Valley, California, United States

Jared Edgar McKnight, Associate ASLA

Faculty Advisors: Aroussiak Gabrielian, ASLA

University of Southern California

This project takes a unique approach to soil rebuilding through mortuary composting in California. It is a fascinating study with a comprehensive soil index that demonstrates an understanding of the soil systems. From concept to implementation, the strong research led to beautiful form-making that crescendos as you move through the project. Their work shows a high level of care and attention, as well.

- 2021 Awards Jury

Project Statement

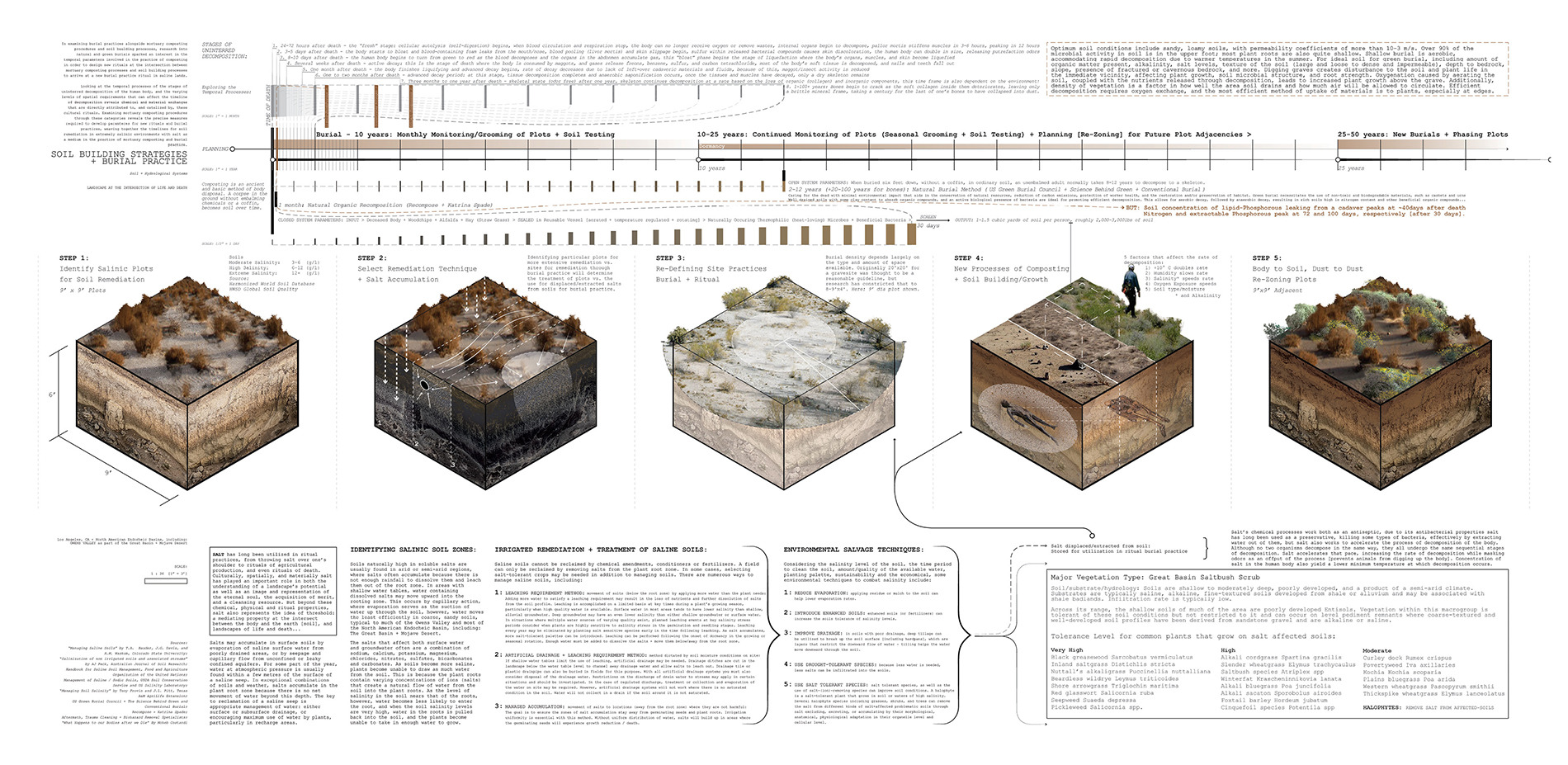

This research project focuses on soil rebuilding processes through the introduction of mortuary composting burial procedures in the semi-arid endorheic basin of the Owens Valley, California. Excess salinity in this region is exacerbated by severe access to water issues and generations of contentious water politics, and constructed hydrologic conditions, that have dammed/damned and depleted regional ecologies, habitats and resources. The proposal defines phased parameters for salinity remediation, while redefining rituals of death to progressively restore the habitat through resilient green burial processes for rebuilding soils. This responsive system of burial morphologies thus awakens an interconnectedness between the burial plot and the dormant ecologies of its context, through an emotive, healing, and emergent topography that unfolds and temporally evolves with one’s own stages of grief and acceptance [or decomposition] over time. Could the future of our burial landscapes facilitate a new form of engagement, whereby our landscapes of life and death reconcile and reconfigure our roles and purpose through one’s own body as a measure of resiliency?

Project Narrative

This design proposal turns our attention downward to the foundation of the landscape – the soil, prompting an exploration into the soils of depleted environmental contexts with looming threats of mass extinction, focusing on soil building processes by rethinking the future of cemetery landscapes. This, is: Dam(m/n)ed Earth.

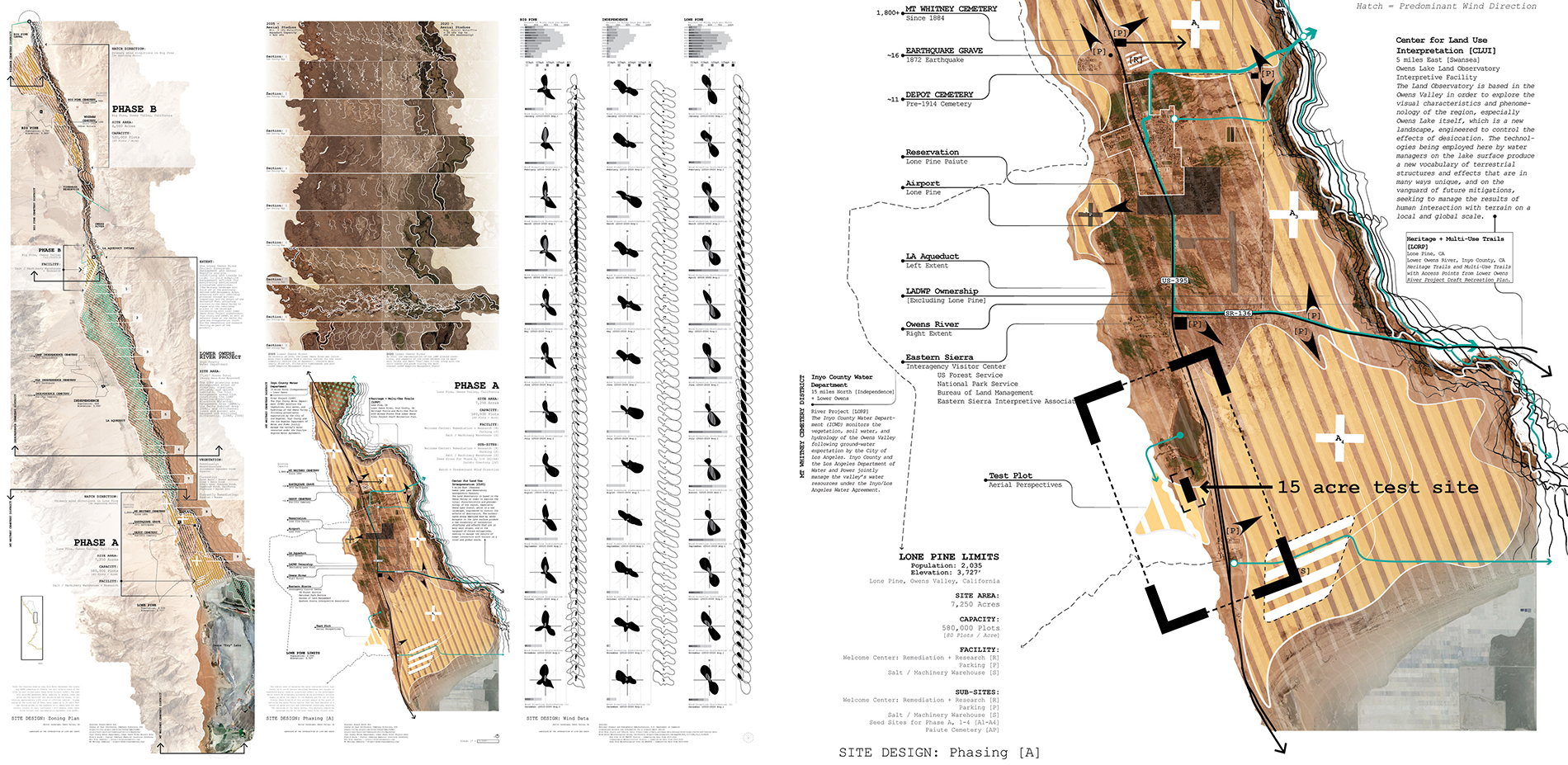

My research began by mapping global issues of salinity in soils, finding that the most salinic soils are within the arid and semi-arid climates of the world’s Endorheic Basins, closed, terminal drainage basins that act as natural dams. Focusing my attention on North America’s Great [Endorheic] Basin I fixated on the Owens Valley north of Los Angeles, to understand the territorial influences contributing to excess salinity, where centuries of water politics and constructed conditions have dammed and depleted water in this area to relieve water stress in another. I became fascinated by the LA Aqueduct, and how its infrastructure breaks the boundary of the Endorheic basin to siphon and supply LA with water, a process that has drastically altered the landscape of the Owens Valley for over a century.

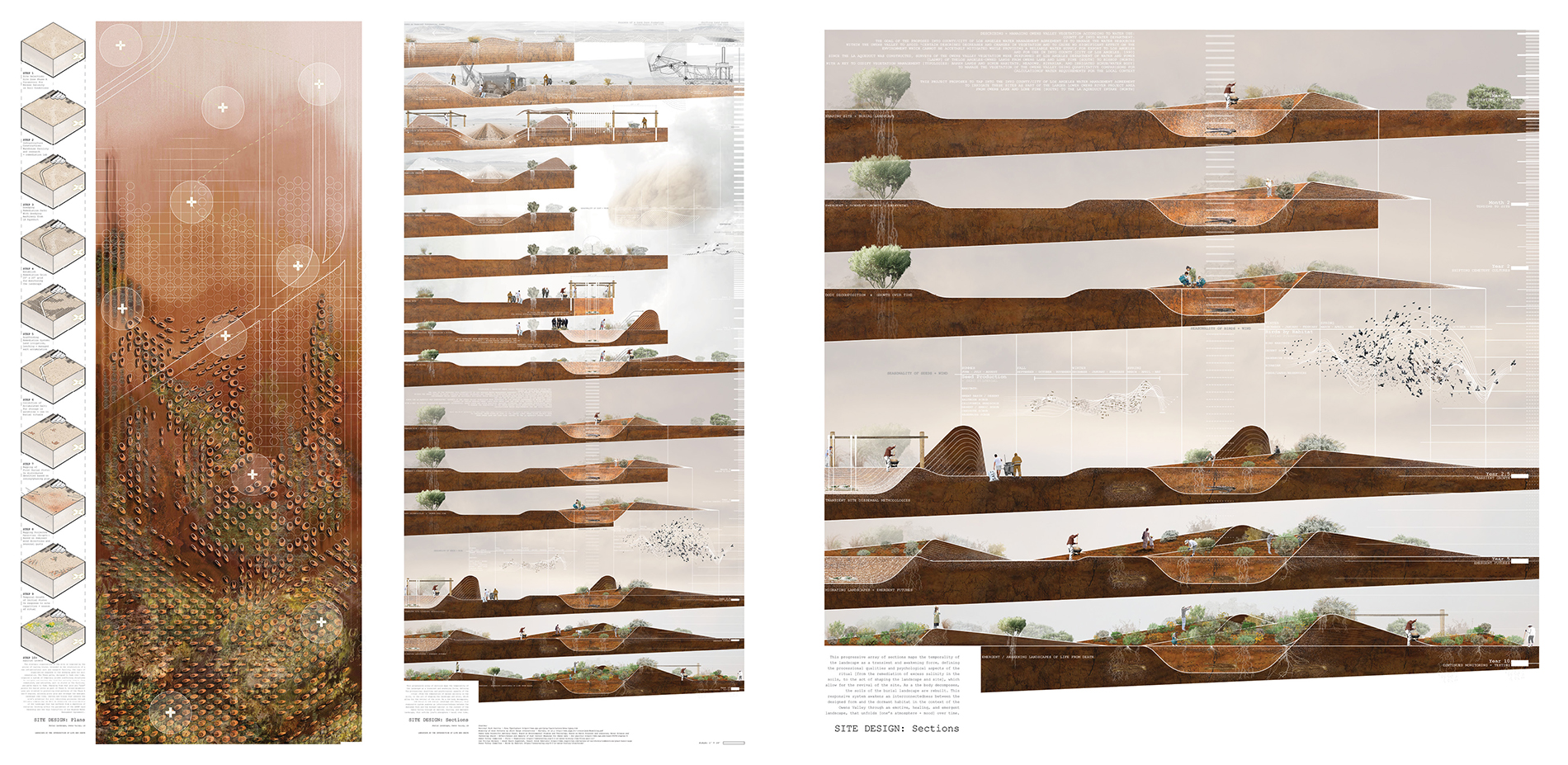

At this regional scale, I situated my focus area for my site between the LA Aqueduct and the natural extent of the Owens River, land controlled by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP). Understanding the larger geological forces, that have shaped this region, its alluvial valley floor, and sediments over time through deep sectional research and drawings, I visited the Owens Valley in March 2020 to explore a context that was once dominated by riparian, meadow, grassland and desert scrub vegetation, but today is dominated only by desert and xeric scrub communities, having suffered significant vegetation loss due to salinic soil conditions after the LA Aqueduct’s construction (and resultant depletion of water resources).

Along my trek, I collected and irrigated soil samples, and began to notice dormant seeds forming roots and sprouting. 5 days later, we entered lockdown.

On the cusp of the global pandemic, where questions of mass extinction were a daily conversation, it was eerily timed that the next phase of my work began examining burial practices and mortuary composting procedures. I began researching green burials, and the temporal parameters involved in the practice of human composting. These temporal processes of decomposition revealed a timeline of chemical and material exchanges that could support a new burial ritual for cemeteries in salinic lands, whereby salt extracted through soil remediation techniques is re-used as a medium in the burial ritual (benefiting from salt’s chemical properties as an antiseptic, and an accelerator in the decomposition process) to redefine a green cemetery that converts body to soil to restore ecological potentials.

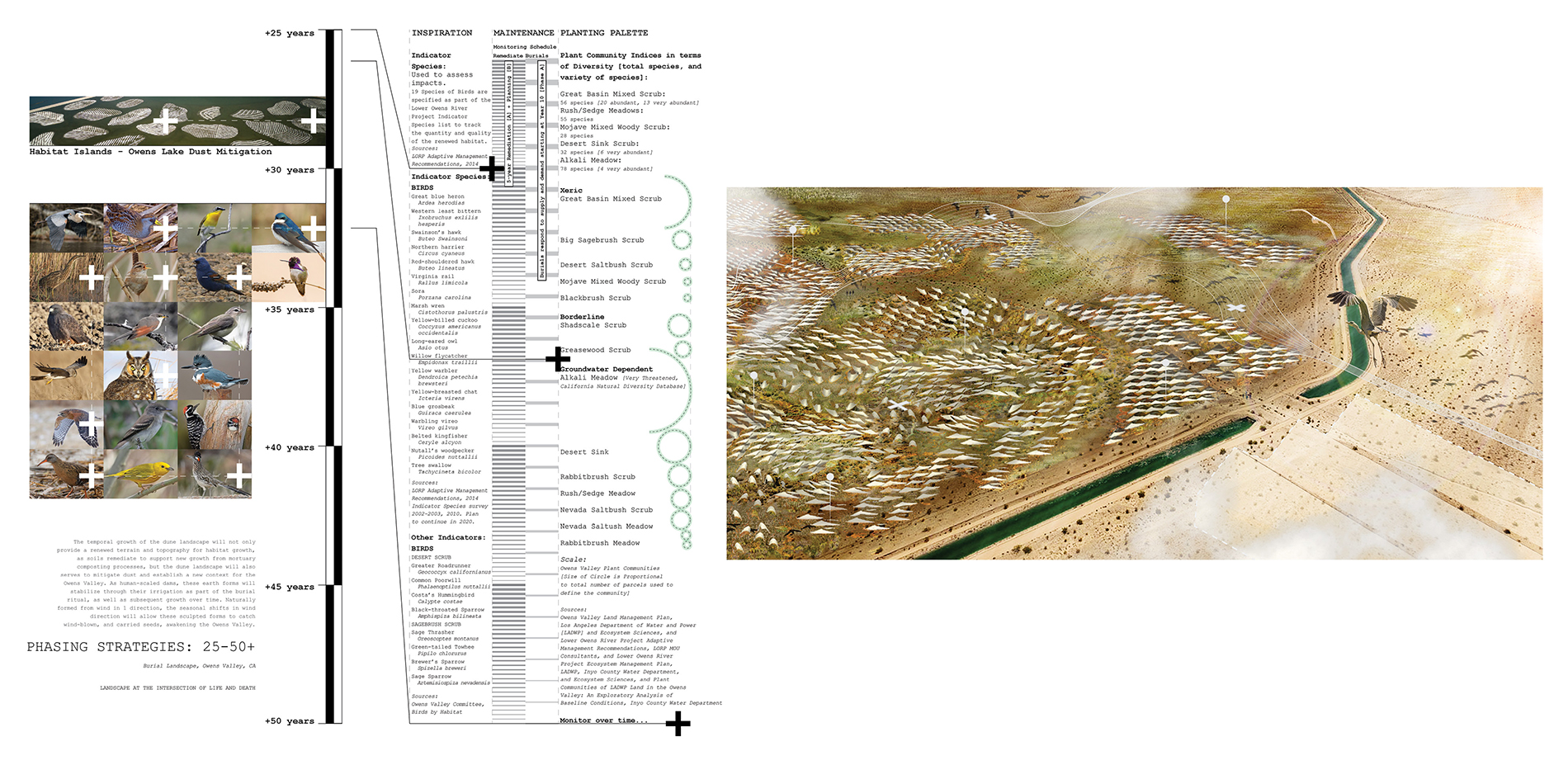

Focusing these parameters within a 2-phase Cemetery Master Plan north of Owens Lake, cemetery sites respond to contexts with salinity issues, loss of habitat, and changing seasonal wind patterns that inform the directionality of the design’s remediation, and growth, over time.

Phase A’s capacity for 580,000 burial plots across 7,250-acres, harnesses initiatives like the Lower Owens River Project, working with the Inyo County Water Department and LADWP to redistribute portions of water siphoned by the LA Aqueduct for ecological restoration. This remediation and cemetery design concept is further explored in the design of a 15-acre test-site.

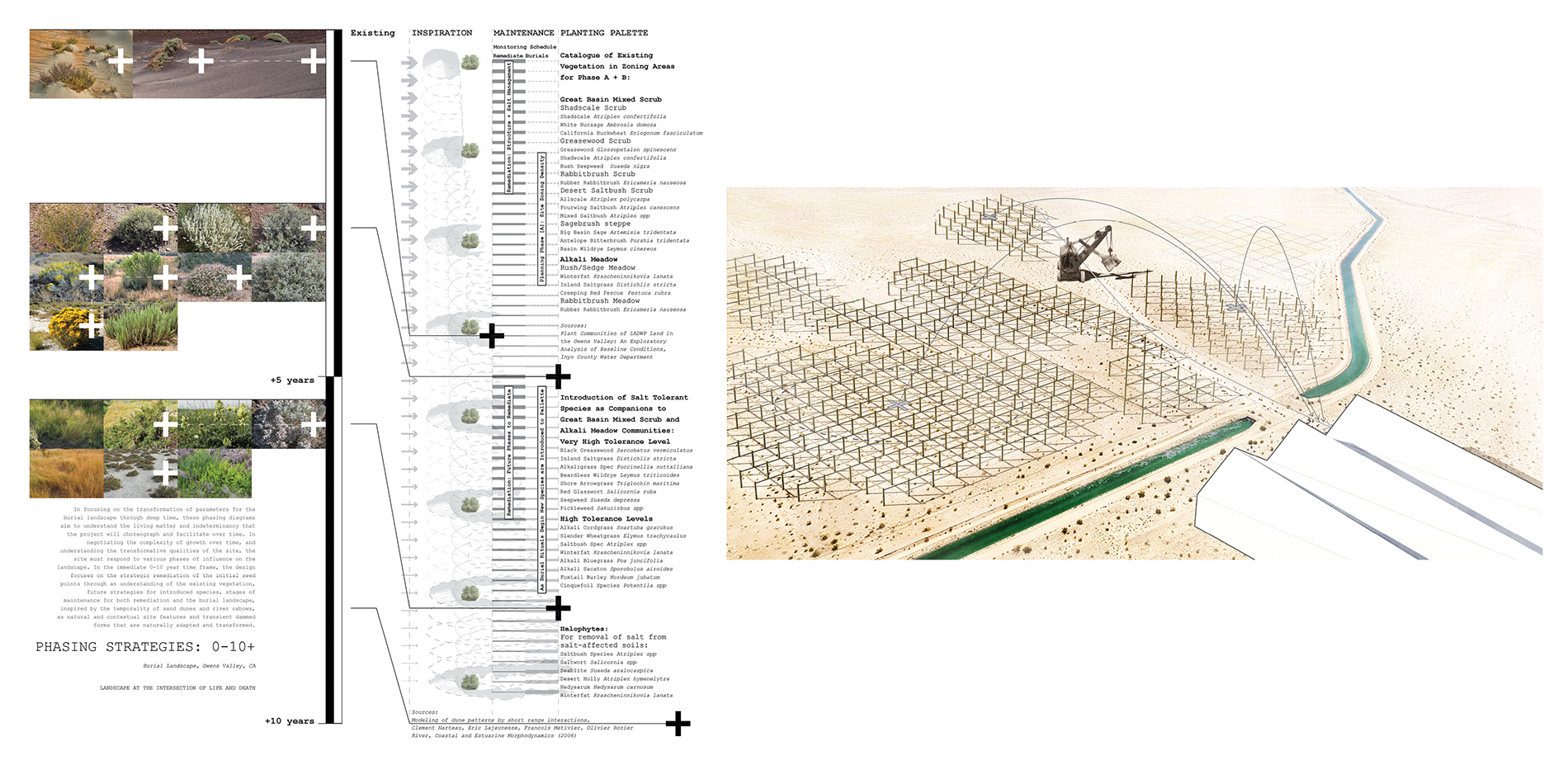

The remediation of initial salinic soil sites employs a wooden scaffolding structure to irrigate and monitor salt extraction, employing irrigated remediation techniques for the treatment of the saline soils (including: the leaching requirement method, artificial drainage, and managed accumulation). During this process, Great Basin Mixed Scrub and Alkali Meadow plant communities are researched for future strategies to restore these depleted habitats, and introduce salt-tolerant species as companions to lost plant communities.

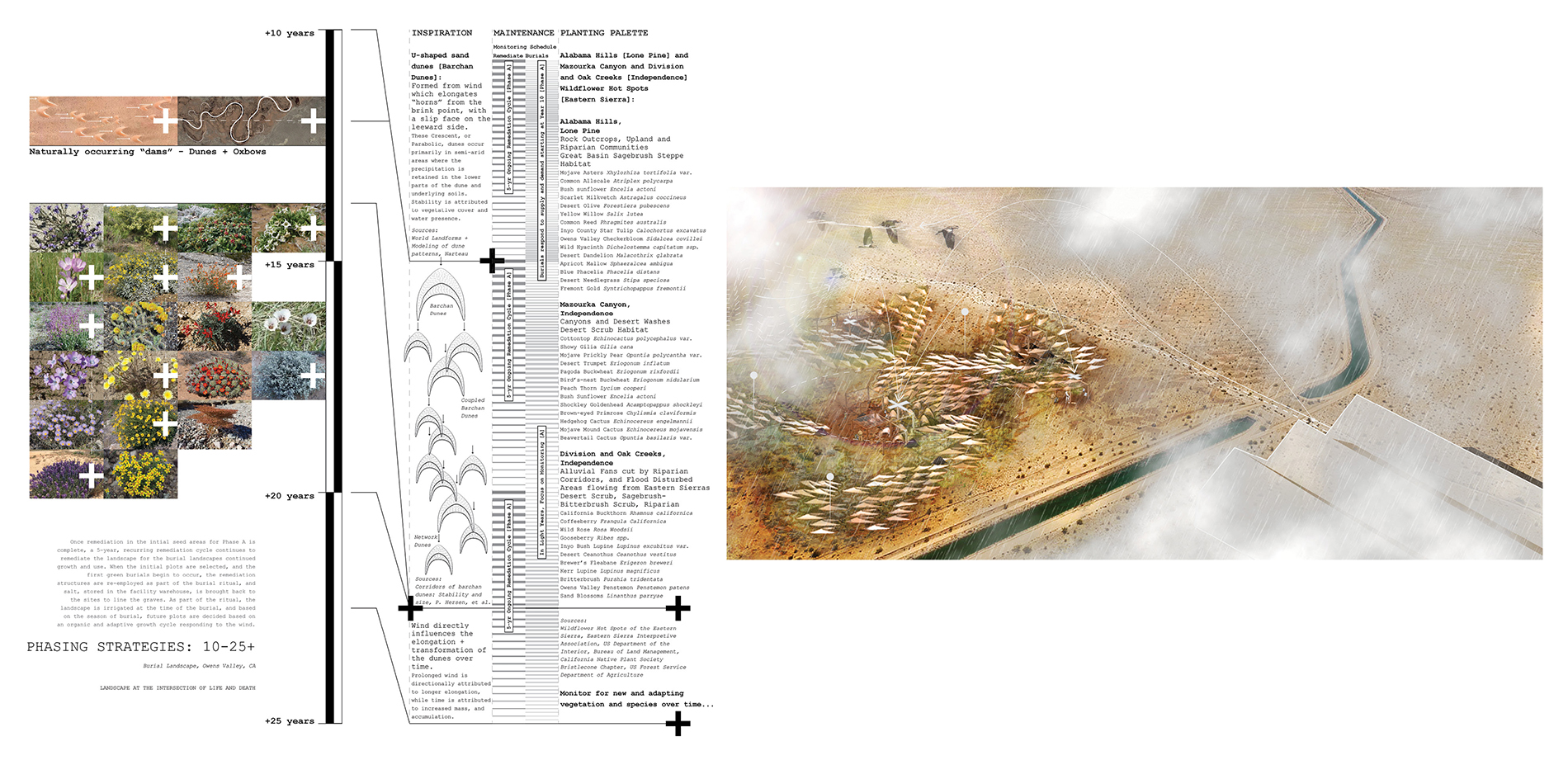

Once salt is extracted from soils, the scaffolding structure is re-deployed as part of the green burial ritual. Grave sites are sited by 9’ diameter plots, spaced at 15’ on center. When burial plots are dug, extracted salt is used to line the graves before burial. During burial rituals, salt-lined plots are then covered with soil, and the displaced soil is formed into a dune around the site, and the dune is seeded with Owen’s Valley wildflowers and irrigated at the time of burial. The site is monitored through drone imagery to geo-locate grave sites and catalogue changes in the site and habitat over time.

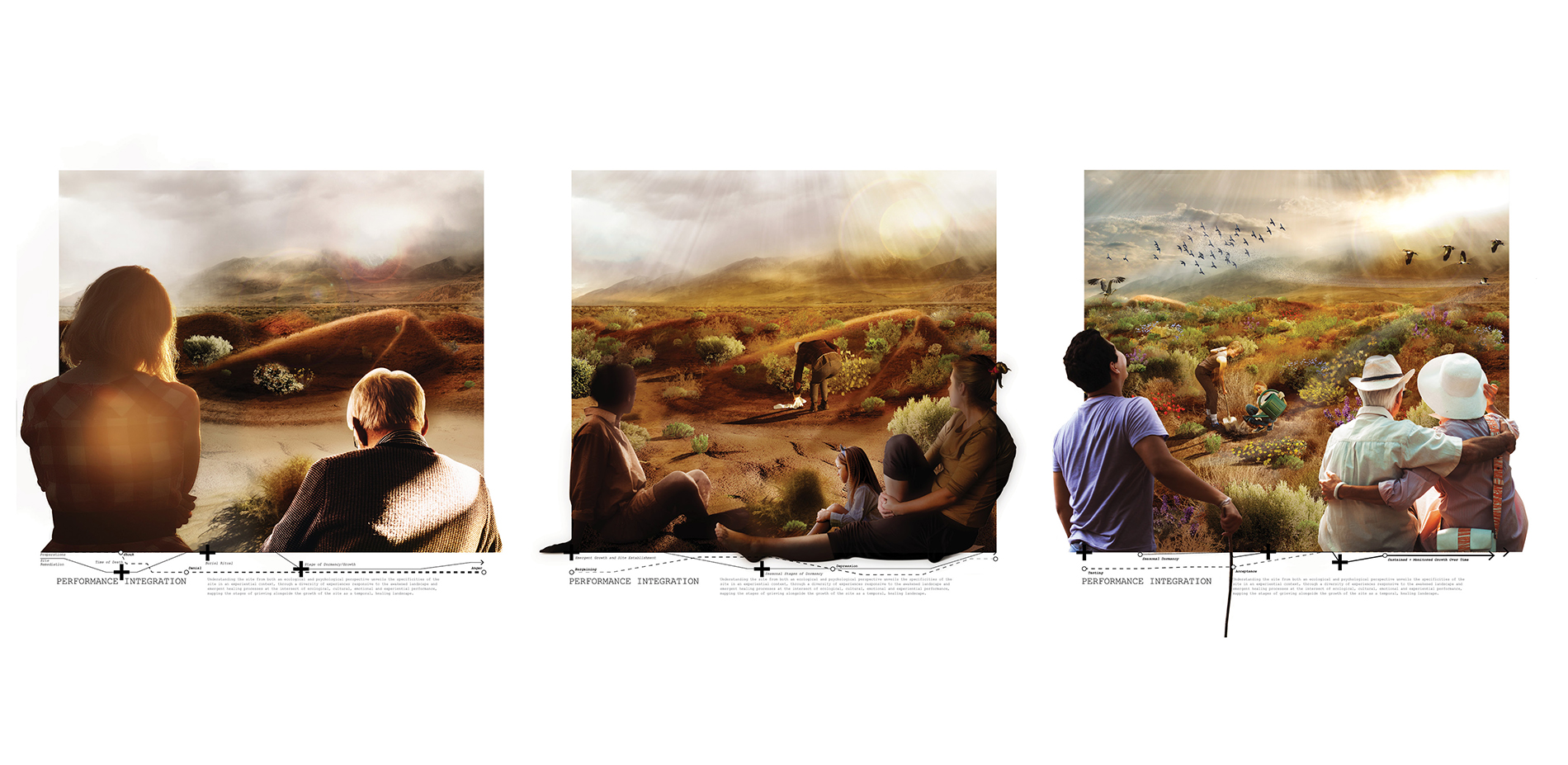

The geo-located database allows loved ones to return to a newly awakened site with each subsequent visit. These sculpted earth forms respond to the directionality of seasonal wind patterns, allowing the dunes to sprout dormant seeds, and catch wind-blown and carried seeds. The growth of the cemetery provides a new ecological context for the Owens Valley, that expands habitat, and monitors indicator species of birds to assess the impact of the project in reclaiming lost biodiversity.

The sites are not defined by physical gravestone markers. The true marking of the grave site and burial plot is its evolution over time. As soils rebuild, one’s afterlife is not so much defined by the confines of the site of their burial, but by the influence that burial has on the larger landscape as a living system.

Mapping the stages of growth alongside one’s stages of grief, the dunes seek not only offer an embrace for the site of the deceased, but to craft an intimate and sensitive relationship with the site at the human scale that honors and respects the site as it grows and changes, supporting soil building capacities, that reclaim biodiversity over time, alongside our own acceptance of loss.

The project is designed to leave traces that will change over time, rooted in a nostalgia for the site, and the deceased, as a resilient entity in the landscape. The design redefines the dormant context of the Owens Valley, through an emotive, healing, personal and responsive landscape that evolves with one’s own stages of grief, acceptance (or decomposition), over time.

Plant List:

- White Bursage, Ambrosia dumosa

- Big Basin Sage, Artemisia tridentate

- Fourwing Saltbush, Atriplex canescens

- Shadscale Sp., Atriplex confertifolia

- Desert Holly, Atriplex hymenelytra

- Allscale Sp., Atriplex polycarpa

- Mixed Saltbush Sp., Atriplex spp.

- Inyo County Star Tulip, Calochortus excavatus

- Desert Ceanothus, Ceanothus vestitus

- Wild Hyacinth, Dichelostemma capitatum ssp.

- Inland Saltgrass, Distichlis spicata

- Mojave Mound Cactus, Echinocereus mojavensis

- Slender Wheatgrass, Elymus trachycaulus

- Rubber Rabbitbrush, Ericameria nauseosa

- California Buckwheat, Eriogonum fasciculatum

- Bird’s-nest Buckwheat, Eriogonum nidularium

- Creeping Red Fescue, Festuca rubra

- Greasewood Sp., Glossopetalon spinescens

- Hedysarum, Hedysarum carnosum

- Foxtail Barley, Hordeum jubatum

- Winterfat, Krascheninnikovia lanata

- Basin Wildrye, Leymus cinereus

- Beardless Wildrye, Leymus triticoides

- Inyo Bush Lupine, Lupinus excubitus var.

- Owens Valley Penstemon, Penstemon patens

- Alkali Bluegrass, Poa juncifolia

- Cinquefoil Sp., Potentilla spp.

- Alkaligrass Sp., Puccinellia nuttalliana

- Antelope Bitterbrush, Purshia tridentate

- Red Glasswort, Salicornia ruba

- Saltwort/Pickleweed, Salicornia spp.

- Black Greasewood, Sarcobatus vermiculatus

- Owens Valley Checkerbloom, Sidalcea covillei

- Alkali Cordgrass, Spartina gracilis

- Alkali Sacaton, Sporobolus airoides

- Seepweed, Suaeda depressa

- Bush Seepweed, Suaeda nigra

- Seablite, Suaeda aralocaspica

- Fremont Gold, Syntrichopappus fremontii

- Mojave Asters, Xhylorhiza tortifolia var.

![Territorial Context: Situating The Great [Endorheic] Basin + Owens Valley in reference to Los Angeles, CA](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/fCepTIFtTtWwpc11ugWA?DamnedEarth-GeneralDesign2-update.jpg)

![Deep [and Shallow] Temporal Sectional Analyses + Fieldwork [Owens Valley, March 10, 2020]](https://cdn.filestackcontent.com/BLG53UcuSHihWmwb3flU?DamnedEarth-GeneralDesign4-update.jpg)