A Garden Can Cultivate an Inmate: Reimagining Youth Incarceration

Award of Excellence

Student Community Service Award

San Luis Obispo, California, United States

Sarah Maloney

Faculty Advisors: David Watts, ASLA

Cal Poly State University, San Luis Obispo

Addressing incarcerated youth through gardening, this project demonstrates a deep dedication to vulnerable populations. It creates a curriculum that illustrates the benefits of gardening rather than just presenting it as another activity that fills the time: gardening becomes more than merely growing food, it becomes about healing. The model could be easily replicable—it can be adapted in many different settings and conditions.

- 2021 Awards Jury

Project Statement

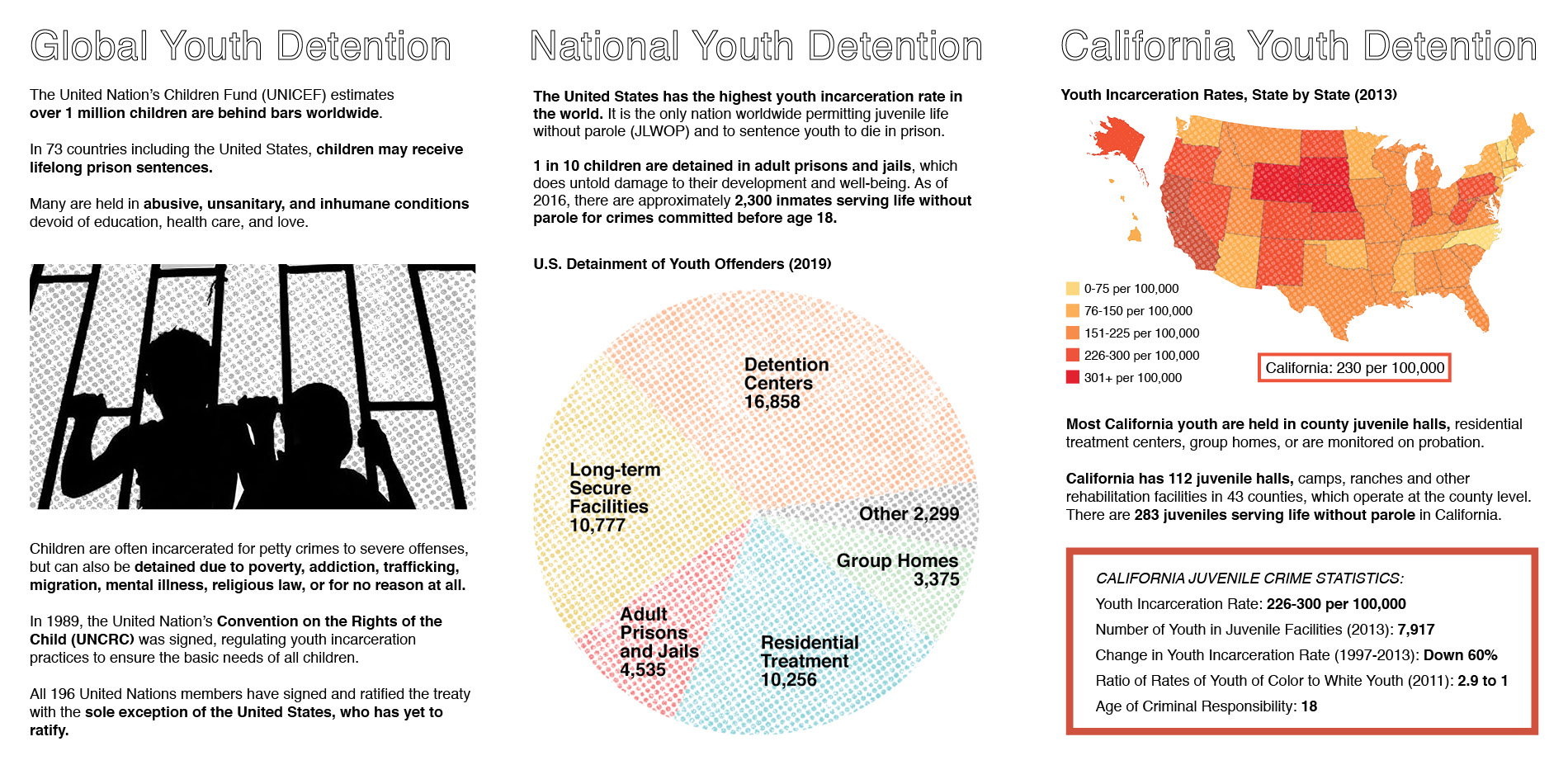

The United States incarcerates more juveniles than any other nation in the world, with nearly 50,000 minors held in detention centers on any given day. This constitutes a mass incarceration crisis which is in dire need of creative reform and interdisciplinary solutions.

Developing effective rehabilitation programs is central in preventing criminal re-offense and providing a path to a better life for millions of affected Americans. A society which truly values its children should value restorative justice over harsh punishment, especially since youth offenders are particularly vulnerable to entering the cycle of adult incarceration.

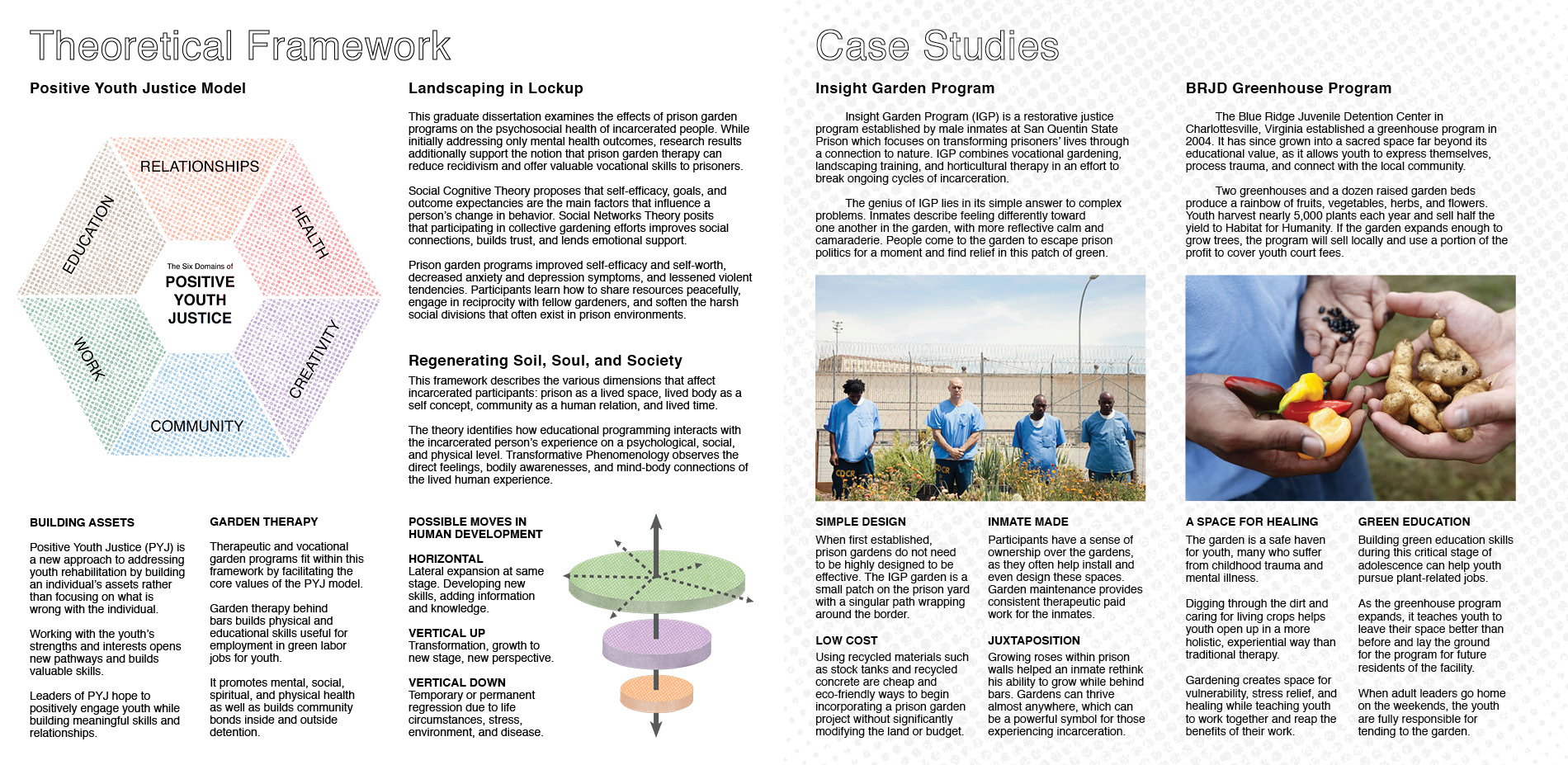

This research-based landscape architecture project proposes therapeutic gardening curriculum as a strategy for youth rehabilitation. While prison gardens certainly cannot solve all the problems associated with incarceration, they can significantly alleviate mental stress, build valuable skills, and help youth cope with life inside and outside prison.

Design that stands for unconditional compassion is powerful. Providing access to nature and green space for every member of society is a fundamental goal of landscape architecture, which includes those who commit crime.

Project Narrative

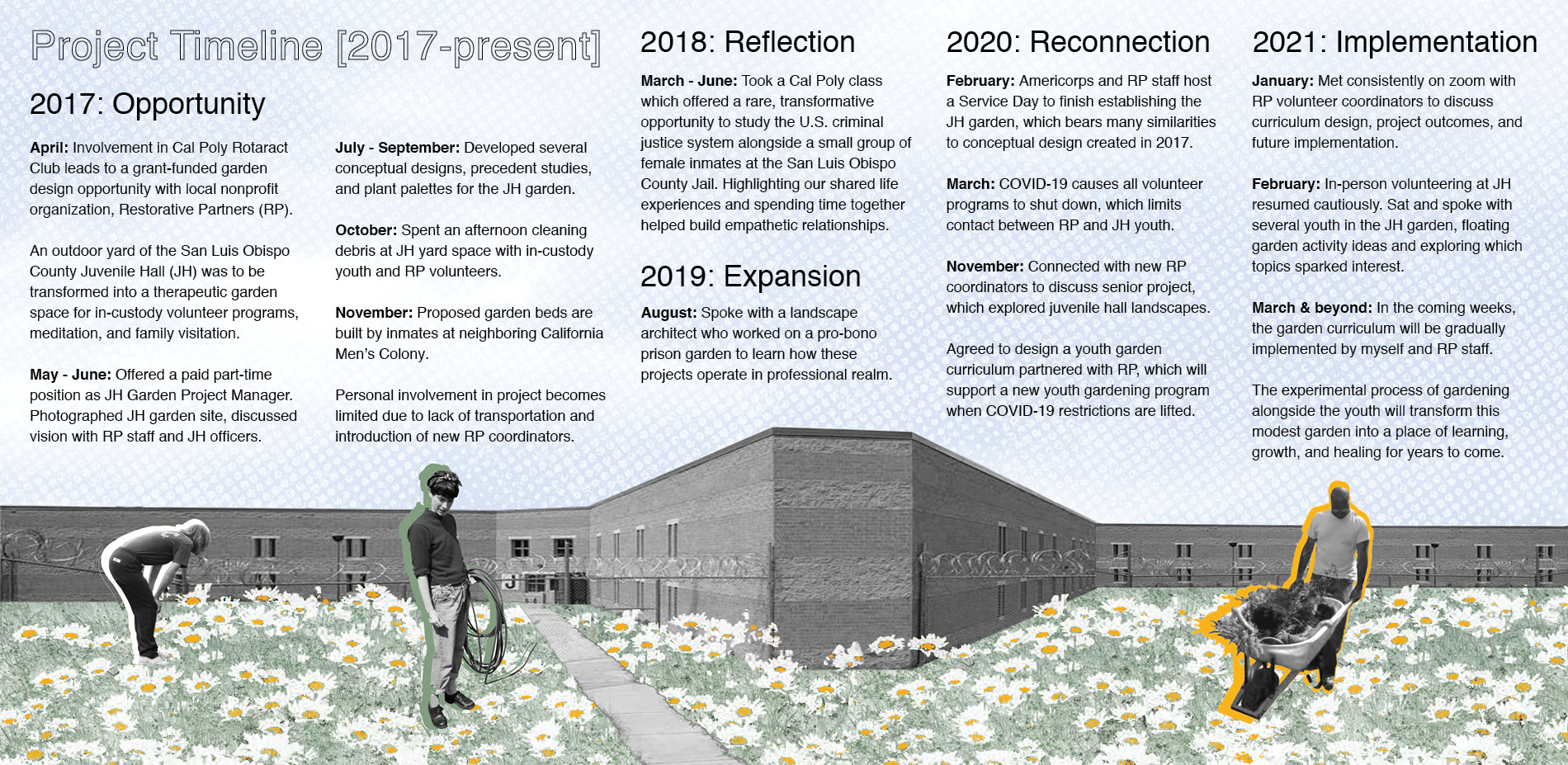

BACKGROUND A Garden Can Cultivate an Inmate is a synthesis of restorative justice research, garden design experience, direct community engagement, and coordination with a local non-profit organization. This project offers resources useful in establishing robust juvenile hall garden programs, which is a complex yet rewarding process. It informs readers on the current state of juvenile justice, provides landscape design recommendations based on first-hand experience, and offers an educational garden curriculum book suited for youth users under age 18. My direct experience with incarcerated people, correctional staff, and community activists has encouraged me to confidently implement this project while balancing stakeholder interests.

As a first-year landscape architecture student in 2017, I collaborated with a non-profit and a local juvenile detention facility to conceptually design a therapeutic garden space for youth programming and visitation. When the youth garden space was fully established in 2020, I volunteered to fully design and lead a youth gardening program, which has been occurring weekly since February 2021. This process opened my eyes to the intersection of landscape architecture and social equity, which manifests through effective therapeutic prison garden programs. I have had the opportunity to fully implement the project, which has given me deep insight into the realities of youth incarceration, the importance of consistent engagement, and the incredible healing power of gardening.

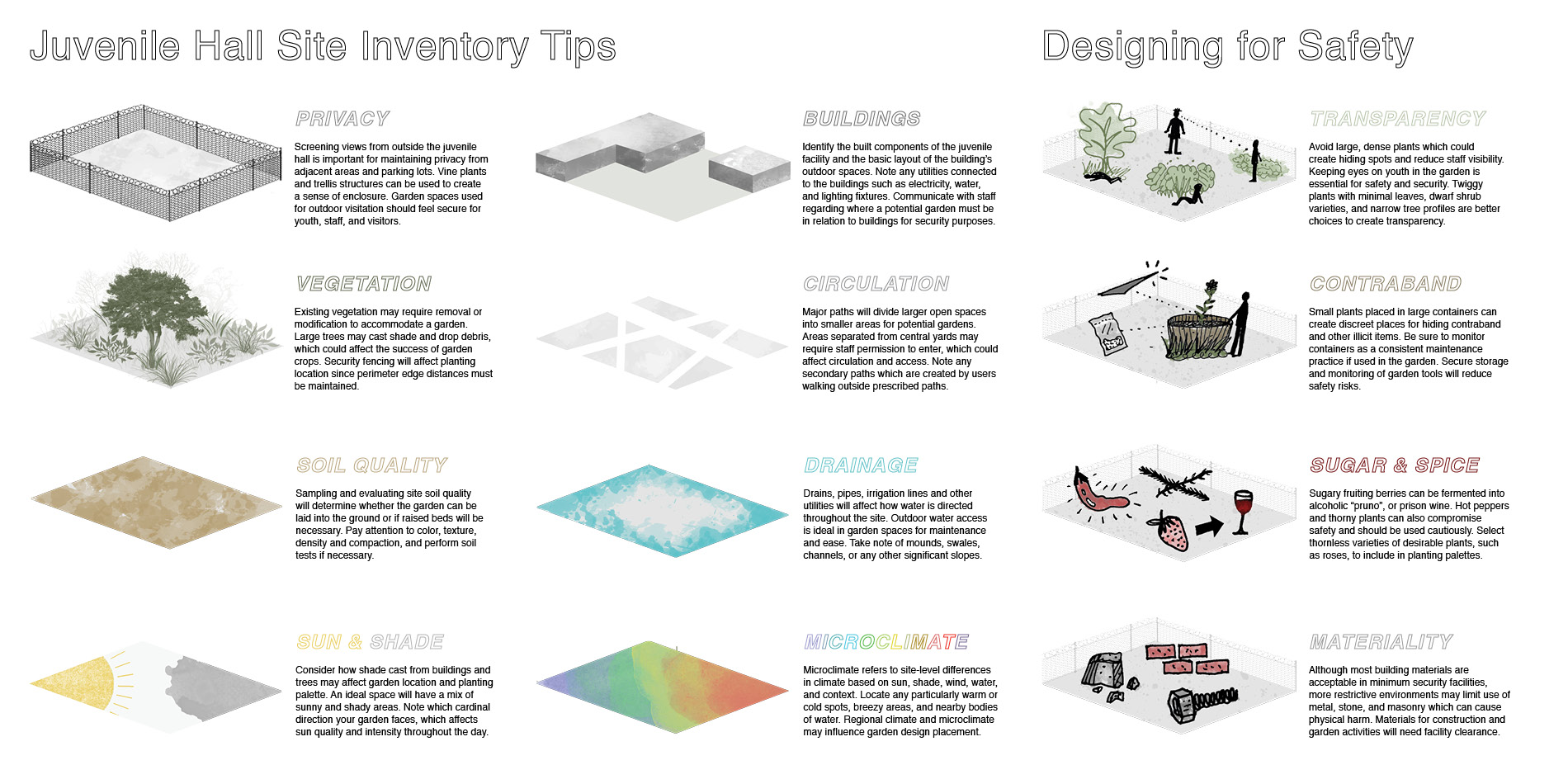

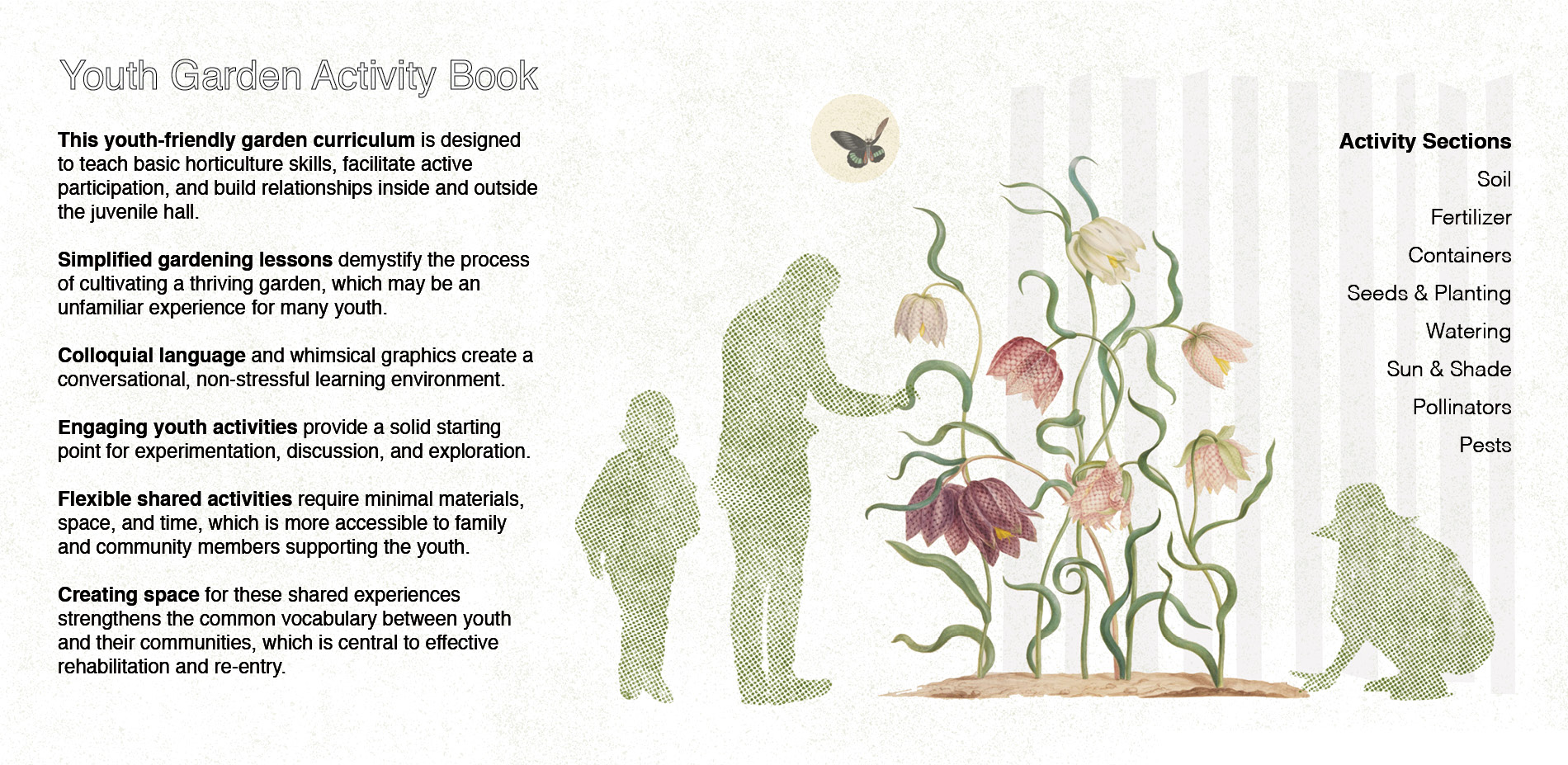

MISSION & GOALS Integrating therapeutic garden education into the rehabilitation practices of U.S. juvenile corrections will empower young people to build valuable skills, connect with loved ones, and escape the adult prison system. A Garden Can Cultivate an Inmate consists of three main sections: research, design, and curriculum. The research component of this project illustrates the current state of youth incarceration, analyzes relevant case studies, and aligns the project within a theoretical garden education framework. Proposing garden therapy as a highly effective, evidence-based rehabilitation strategy supports the future implementation of similar programs throughout the United States. The design recommendation section provides lessons for designing in carceral spaces, especially in the realm of youth safety and security. My experience designing for a juvenile detention hall and working with correctional staff informed the guidelines created in this section. Finally, the youth garden curriculum provides an easily printable booklet with teaching material and suggested activities. This book provides a solid starting place for youth, volunteers, staff, or anyone interested in participating in garden education for those with little to no knowledge of the subject.

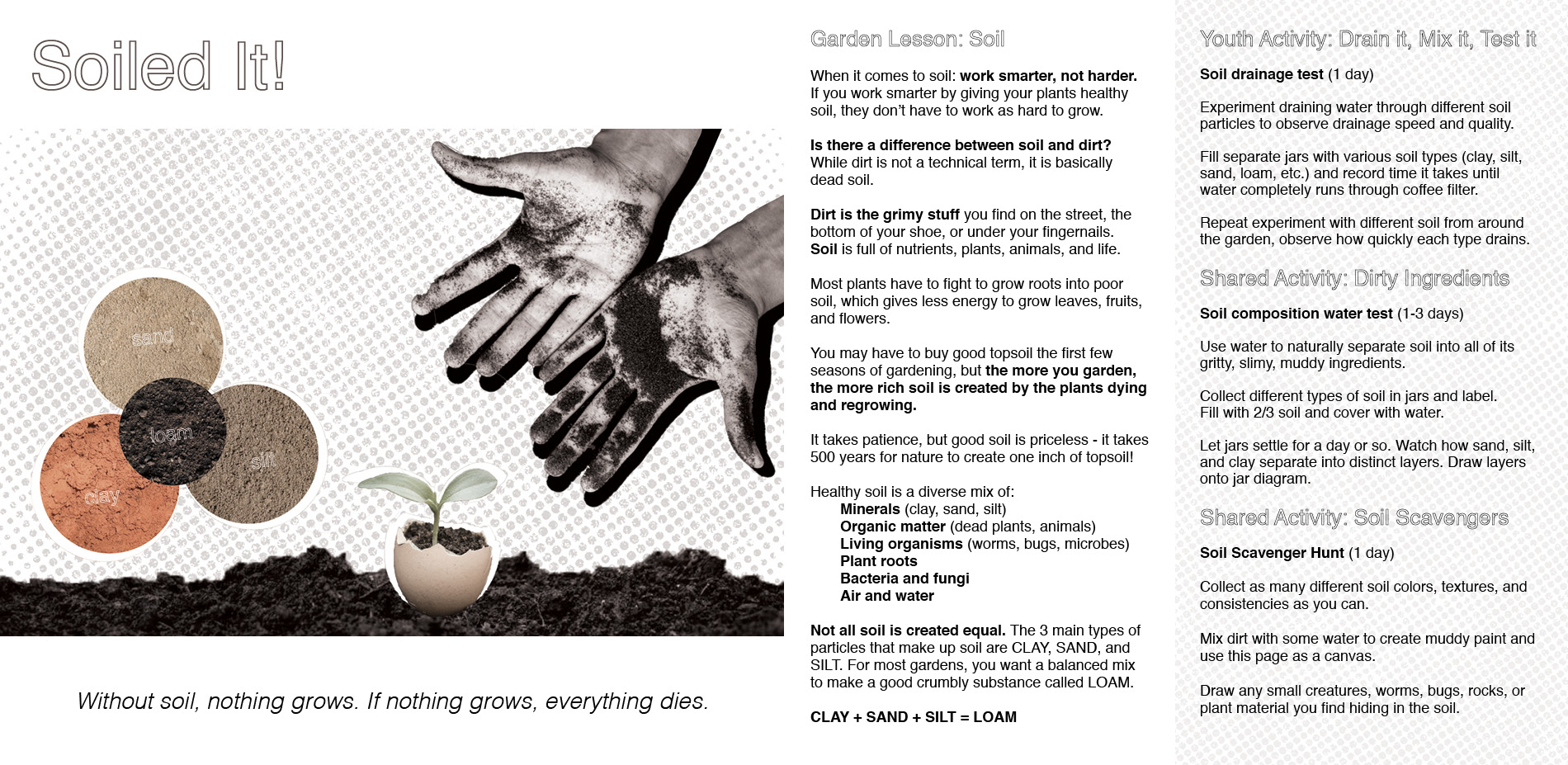

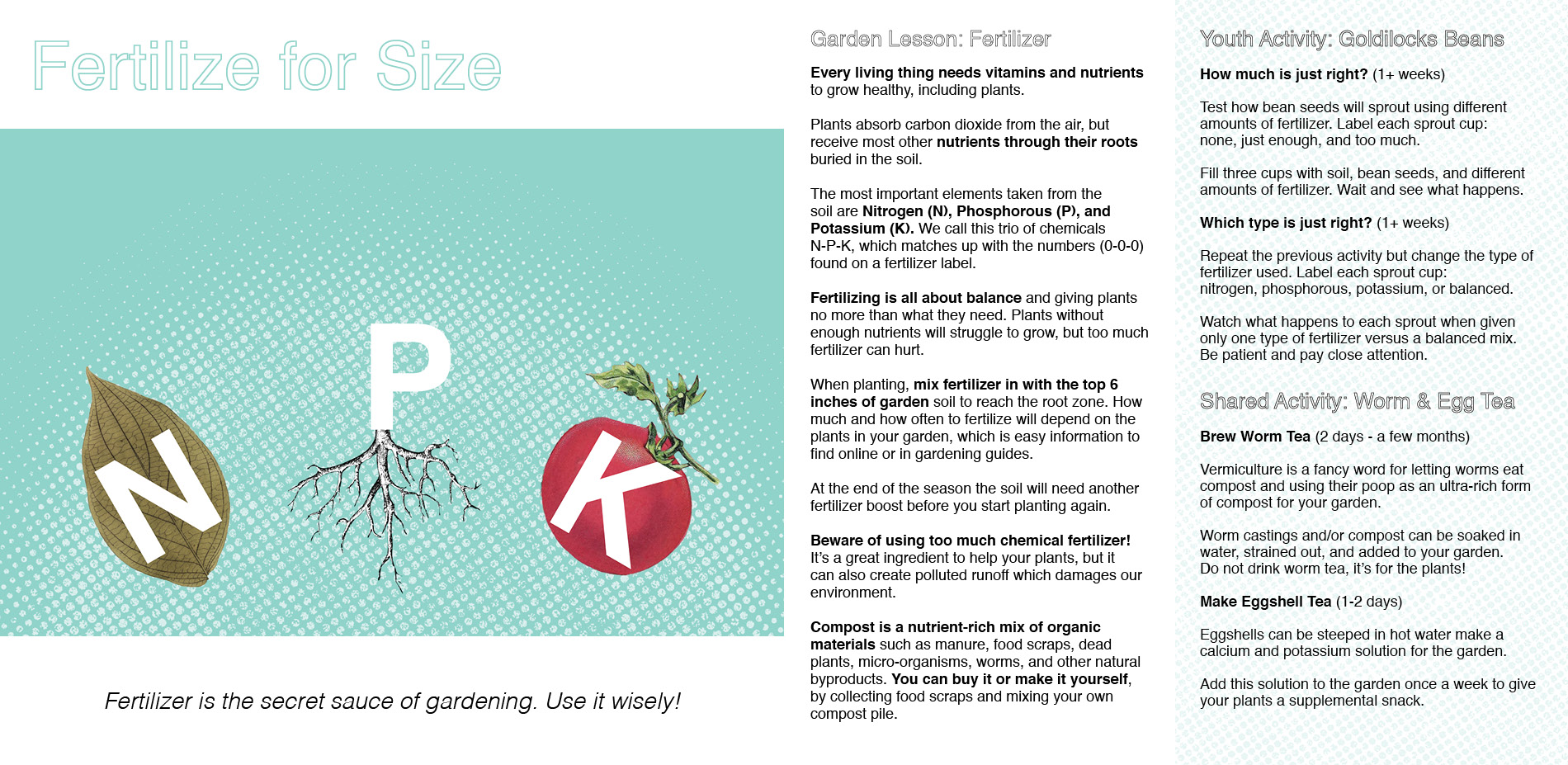

Bringing garden education and vibrant green space into juvenile detention honors the humanity of incarcerated youth and builds relationships through the shared experience of gardening. The youth garden curriculum book provides low-cost, engaging activities which teach the basic components of a healthy garden and its maintenance. Each curriculum section offers a garden lesson, a youth activity intended for juvenile hall gardens, and several shared activities which can also be easily completed by friends, family, and community members outside detention. Creating space for parallel experiences strengthens the common vocabulary between youth and their communities, which is central to effective rehabilitation and re-entry.

SOCIAL EQUITY, DIVERSITY, & INCLUSION Youth with the greatest need for rehabilitation and care are typically victims of several harmful childhood experiences which impede healthy development. Early childhood trauma can have long lasting effects and often contributes to the behavioral problems that bring youth into the system. Youth of color who deal with the pressures of poverty and abuse early in life are more vulnerable to the cradle-to-prison pipeline, which can be incredibly difficult to escape if they are only punished rather than rehabilitated. The vast majority of incarcerated youth are young black and brown men, who are disproportionately detained more than their white peers. Black, Native American, and Latino youth are overrepresented in California and the U.S. juvenile justice system as a whole.

Young people exist at a critical crossroads of mental and emotional development, which means they are not entirely capable of making rational choices. This does not absolve youth who commit severe crimes, but reminds us that children are susceptible to change and growth. Treating adolescents as criminals for minor transgressions establishes a crime record which often follows them into the future, which disproportionately affects youth of color.

Diverting youth from the criminal justice system and providing community-based, culturally-responsive services has yielded positive results for getting youth back on track. Incarceration reformists argue that a fundamental shift in the foundational principles of juvenile incarceration should be re-evaluated in favor of robust rehabilitation resources. Positive Youth Justice is a new approach to addressing youth rehabilitation by building an individual’s assets rather than focusing on what is wrong with the individual. Working with the youth’s strengths and interests opens new pathways, builds valuable skills, and promotes holistic growth. Therapeutic and vocational garden programs can also build physical and educational skills useful for employment in green labor jobs for youth.

COLLABORATION WITH STAKEHOLDERS This project would not have been possible without the trusting relationships built with staff at Restorative Partners and cooperation with SLO Juvenile Hall correctional staff. From the earliest stages of conceptual design through the current state of the garden program, Restorative Partners staff have always valued empathy, creativity, and passion, which has made this project possible. Collaboration most often occurred between myself and the volunteer coordinators, with whom I virtually met biweekly over a 6-month period to discuss the progression of the project. Consistently discussing logistics, feasibility, and visions for the garden program provided momentum through the long months of COVID-19 lockdown, during which in-person volunteering was suspended.

When restrictions cautiously opened up in mid-February, I was able to sit down with several youth in the outdoor space and discuss how they felt about participating in garden activities. Incorporating youth ideas and feedback into the project was essential to keeping the project grounded in reality. Receiving feedback, ideas, and suggestions from correctional staff regarding the garden program has also been highly encouraging and informative. As I continue to interact weekly with youth, staff, and Restorative Partners, I become more confident in the immense potential of gardening in strengthening community bonds.

PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION Beyond the research, theory, case studies, and design presented in this project, real life implementation entails an entirely new set of challenges and opportunities. Several months into the new youth garden program, the space has slowly transformed into a haven full of edible plants and blossoming greenery. Consistently attending weekly sessions with new materials, activities, and plants has allowed me to authentically build trust with the youth, who show a growing interest in gardening every week. Their willingness to be vulnerable, openness to learning, and enthusiasm for experimentation has been truly inspiring. I will see the program through the end of 2021, after which I will recruit and mentor a new lead garden volunteer to carry on this vibrant space. I intend to pursue prison garden therapy in my career, and I am grateful for the opportunities to directly work with affected communities throughout my undergraduate degree.