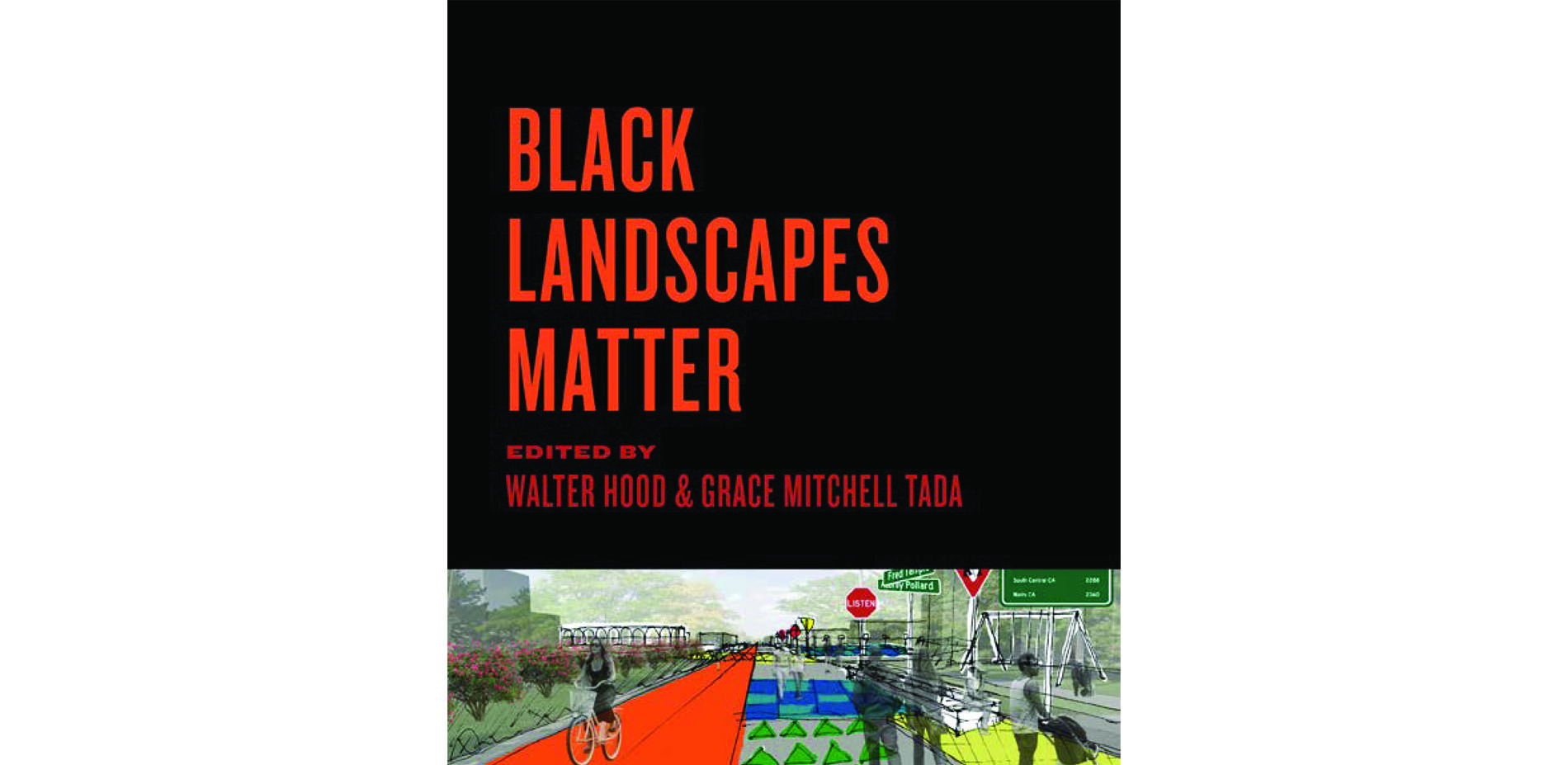

Black Landscapes Matter

Award of Excellence

Communications

Walter Hood

Grace Mitchell Tada, Associate ASLA

Black Landscapes Matter is a timely revelation of sometimes painful truths about places across the United States where injustices have been embedded, confronting them in a way that promotes restorative action toward a more just terrain. That justice can be applied unilaterally, reconciling our collective past, but then also gives people the space to envision themselves in the future. The book elevates and amplifies eighty-seven voices to tell their powerful stories, celebrating the very difference of those voices as it expands understanding and appreciation of how Black landscapes matter.

- 2021 Awards Jury

Project Credits

Boyd Zenner, Senior Acquiring Editor, UVA Press

UVA Press, Publisher

Austin Allen, Contributing Author

Kofi Boone, Contributing Author

Anna Livia Brand, Contributing Author

Maurice Cox, Contributing Author

Sara Daleiden, Contributing Author

Richard Hindle, Contributing Author

Louise Mozingo, Contributing Author

Lewis Watts, Contributing Photographer

Project Statement

In the volume Black Landscapes Matter (UVA Press, 2020), editors Walter Hood and Grace Mitchell Tada bring together landscape architecture and planning professionals to probe how race, memory, and meaning intersect in the American landscape. The authors examine diverse places across the US and assert these landscapes as canvases that shape individual and communal identities. Through critique, celebration, and examination, they call for the recognition of these places as paramount for enabling a comprehensive reading of the American landscape. Over 1,000 copies of the book have already been sold, and the volume is currently in its third reprinting. The success of the book speaks to the demand within the built environment professions, and specifically landscape architecture, to address issues of race, equity, and truthful cultural memory. Black Landscapes Matter serves as a starting point for conversations in communities across the US working toward equitable and just public spaces, and is a timely and necessary reminder that without recognizing and reconciling these histories and spaces, America’s past and future cannot be understood.

Project Narrative

The volume Black Landscapes Matter, edited by Walter Hood and Grace Mitchell Tada, poses the question “Do black landscapes matter?” From the plantations of slavery to contemporary segregated cities, from freedman villages to northern migrations for freedom, the nation’s landscape bears the detritus of diverse origins. Black landscapes matter because they tell the truth. To elucidate these truths, acclaimed landscape designer and public artist Walter Hood assembles a group of notable landscape architecture and planning professionals and scholars to probe how race, memory, and meaning intersect in the American landscape.

Essayists examine a variety of U.S. places—ranging from New Orleans and Charlotte to Milwaukee and Detroit—exposing racism endemic in the built environment and acknowledging the widespread erasure of Black geographies and cultural landscapes. Through a combination of case studies, critiques, and calls to action, contributors reveal the deficient, normative portrayals of landscape that affect communities of color and question how public design and preservation efforts can support people in these places. In a culture in which historical omissions and specious narratives routinely provoke disinvestment in minority communities, creative solutions by designers, planners, artists, and residents are necessary to activate them in novel ways. Black people have built and shaped the American landscape in ways that can never be fully known.

The volume is organized by chapter as follows:

Walter Hood opens the volume encouraging landscape architects and those in related disciplines to develop a “prophetic” aesthetic language to remember and develop new futures from the power of the past. Only in doing so can history be corrected as truth.

Designer and educator Richard Hindle offers a sobering view of the 2016 presidential election and surrounding events that have revealed the centuries-long institutional and embodied racism latent in countless forms across the United States. It is evident, he writes, that Black landscapes matter to everyone. They form the core of American history—from early colonial and plantation landscapes, to Seneca Village in Central Park. Yet, as a whole, our culture knows little of them. It is overdue that we shift that understanding.

Landscape historian Louise Mozingo considers her childhood move from Rome, Italy, to Arlington, Virginia, and the corresponding shift in how she experienced the public realm. In the US, Mozingo initially confronted race and Blackness in the landscape: she recalls her slow realization of the nonsensical, racist divisions that governed the American public realm. They still do today, and it is these physical divisions that preserve myriad other divisions throughout the country. As long as these divisions persist, designing the public realm continues to be urgent work.

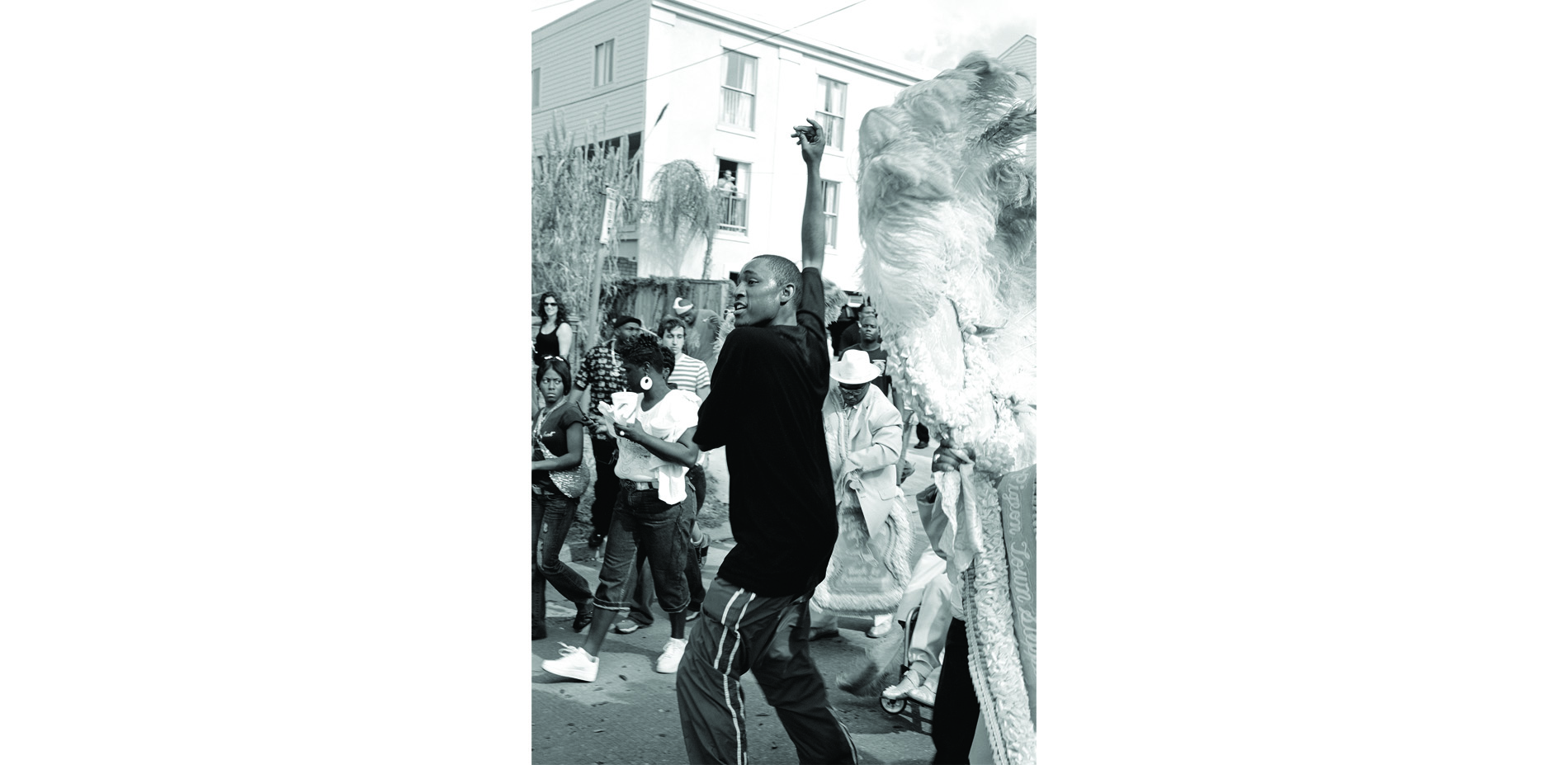

Dr. Anna Brand documents the everyday and mundane life pre- and post-Hurricane Katrina on the 4800 block of Camp Street, in the Uptown neighborhood of New Orleans. Between 2003 and 2017, she witnessed the shifting and displacement of people within a Black geography in a post-catastrophic context where gentrification was cloaked in the politics of rebuilding. Brand argues that although these Black geographies were created out of apartheid racial systems, they are not defined by racism. She points to the specificities and the creative patterns inherent in these landscapes as keys to establishing their future.

North Carolina–based designer, educator, and environmental-justice advocate Kofi Boone builds from the groundwork of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement and asks if the field of landscape architecture can be reconsidered as a vector of community empowerment. Referencing the creative production surrounding BLM, he notes that the built environment professions have been excluded from this wave. A contemporary reconfiguration of the education and professional system would enable African American participation in shaping the American landscape—and recognize their long history of doing so, evidenced in plantation landscapes, HBCU campuses, political and economic urban spaces, and planned communities. Boone also recognizes the role of public space in developing Black leadership through the rise of Black Wall Streets, creative protest, and the environmental justice movement.

Hood recalls with nostalgia his childhood in a post-civil-rights but still-segregated Charlotte, North Carolina, in the 1960s and ’70s, and discusses the evolution of Charlotte since his childhood. He examines census data and public art, and harnesses geographer David Lowenthal’s essay “Past Time, Present Place: Landscape and Memory” to articulate his understanding of the city’s transformation. The paradox of the Black landscape in the urban United States, writes Hood, is its celebrated presence in the collective American consciousness despite its physical erasure. Hood posits that his hometown’s memory of Black landscapes presents a version of the past—an ostensible past—that never was.

Maurice Cox, writing from his post as planning director of the City of Detroit, shares his professional journey as an architect, politician, and activist that has taken him across the United States. He recognizes the tendency of the American landscape to erase certain histories—particularly those of African American communities. It is these communities themselves, Cox argues, who must preserve and steward these spaces, like the Bayview community in rural Virginia that demonstrates self-determination, and like New Orleans, a landscape shaped by multicultural heritage. Arriving in Detroit, Michigan, Cox asks how urban planning considers a landscape of disinvestment and Black disenfranchisement. His answers include recognizing value in the landscape, and respecting the history of the place and its people.

Landscape architect, educator, and filmmaker Austin Allen shares personal narratives across various landscapes, from New Orleans to Ohio, and describes African Americans’ struggle to define and maintain space despite their central role in shaping and cultivating the American landscape. In some places, a racial gaming has allowed Black people’s continued occupation of space. In other instances, place is elusive and improvisational, giving rise to the rituals, rules, interpretations, and negotiations that characterize Black landscapes, communities, and identities. But even in moments of brightness and transgression, these places, because of their dark histories, oscillate between the apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic. Considering the role of education in the celebration of Black landscapes, Allen advocates a renewal of the community college system as a channel by which to validate Black landscapes and Black contributions to the built environment, and empower Black communities in a future laden with uncertainty.

Hood describes the shift in his landscape design work, in the 1990s, toward a language embracing new narratives and representations—and understood by the people whose spaces he designed. He recognizes that photography preceded his thinking. A series of Watts’ photographs portraying Black subjects deeply influenced Hood’s understanding of Black landscape space. Hood selects seventeen of Watts’ images from New Orleans (presented here) that document the Black body and its importance in inclusive space: the Black body as ordinary—not as spectacle—existing in the same space as everyone else.

Artist and civic-engagement facilitator Sara Daleiden discusses collaboration and agency as a tool for ethical cultural development within the context of the Beerline Trail, a “rail to trail” project in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Working along the trail and its border space that carry a legacy of racial segregation practice and policies, Daleiden discusses the Black landscape as a cultural body that can facilitate working through trauma in a city. The trail becomes the “thing” in the landscape that is a lens by which to navigate the neighborhood’s marginalized predicaments and desires.

Hood concludes the volume calling for narratives that showcase the multiplicities latent in the American landscape. Despite the American motto E Pluribus Unum, Hood asserts that it is impossible to have oneness when we live in a nation of multiplicities. Pointing to W. E. B. Du Bois’ understanding that double-consciousness engenders empathy, Hood, too, espouses multiplicity as a means by which to see, accept, and celebrate difference. Black landscapes and their narratives, as well as others similarly buried, demand Americans expand their narrow, normative understanding of vernacular landscapes. Including more complex landscapes in the collective American memory imbues us all with a new consciousness.