Mosswood Park Master Plan and Community Engagement

Honor Award

Analysis and Planning

Oakland, California, United States

Einwiller Kuehl Inc.

LMS Architecture

Art is Luv

Client: Oakland Public Works and Oakland Department of Parks and Recreation

In analyzing Oakland’s Mosswood Park and considering its potential future, landscape architects researched the site’s history, soliciting stories from both displaced and current residents to round out conversations on what the community had been prior to a highway insertion in the mid-1950s. Working with the city’s Geographic Equity Toolbox, the design team began by evaluating equity factors in the park, then worked with the community to establish equity goals for the project to ensure they were prioritized. The engaged constituency participated in a year-long series of workshops and discussions, which yielded collages informed by collective reimagining of the site, resulting in three design options from which a unanimous front-runner emerged, earning city council approval in early 2021.

- 2021 Awards Jury

Project Credits

Sarah Kuehl, Principal at Einwiller Kuehl

Greta Mayne, Designer at Einwiller Kuehl

Alex Broad, Designer at Einwiller Kuehl

Marsha Maytum, Principal at LMS Architects

Ryan Jang, Principal at LMS Architects

Dominique Elie, Associate at LMS Architects

Cecily Ng, Architect at LMS Architects

Charmin Roundtree-Baaqee, Principal at Art is Luv

Stephen DeJesse, President at IDA Structural Engineers

Niall Durkin, Executive Vice President at TBD Consultants

Molly Batchelder, Arborist at SCBA Tree Consulting

Christine Reed, Project Lead at City of Oakland DPW

Mosswood Park Community, Community Input

Project Statement

Championed by place-keeping and a definition of history and historic preservation that includes the last 50 years of social movements and community resistance to structural racism, the Mosswood Park Master Plan is an example of how planning documents can support equity, environmental justice, community stewardship, and community-based design. Beginning with a deep dive into the layers of site history, the process to develop the master plan focused on a series of community engagement workshops and meetings that prioritized listening, collective imagining, and community consensus. The master plan document ultimately defines a framework for planning and future decisions that were identified by the community and has laid out targeted goals that will promote equity, work against structural racism and disinvestment, and improve environmental justice and sustainability in development of the design. The Mosswood Park Master Plan is an example of sustainable design that is rooted in equity, community and most importantly has defined measures for accountability.

Project Narrative

Site History + Project Framework

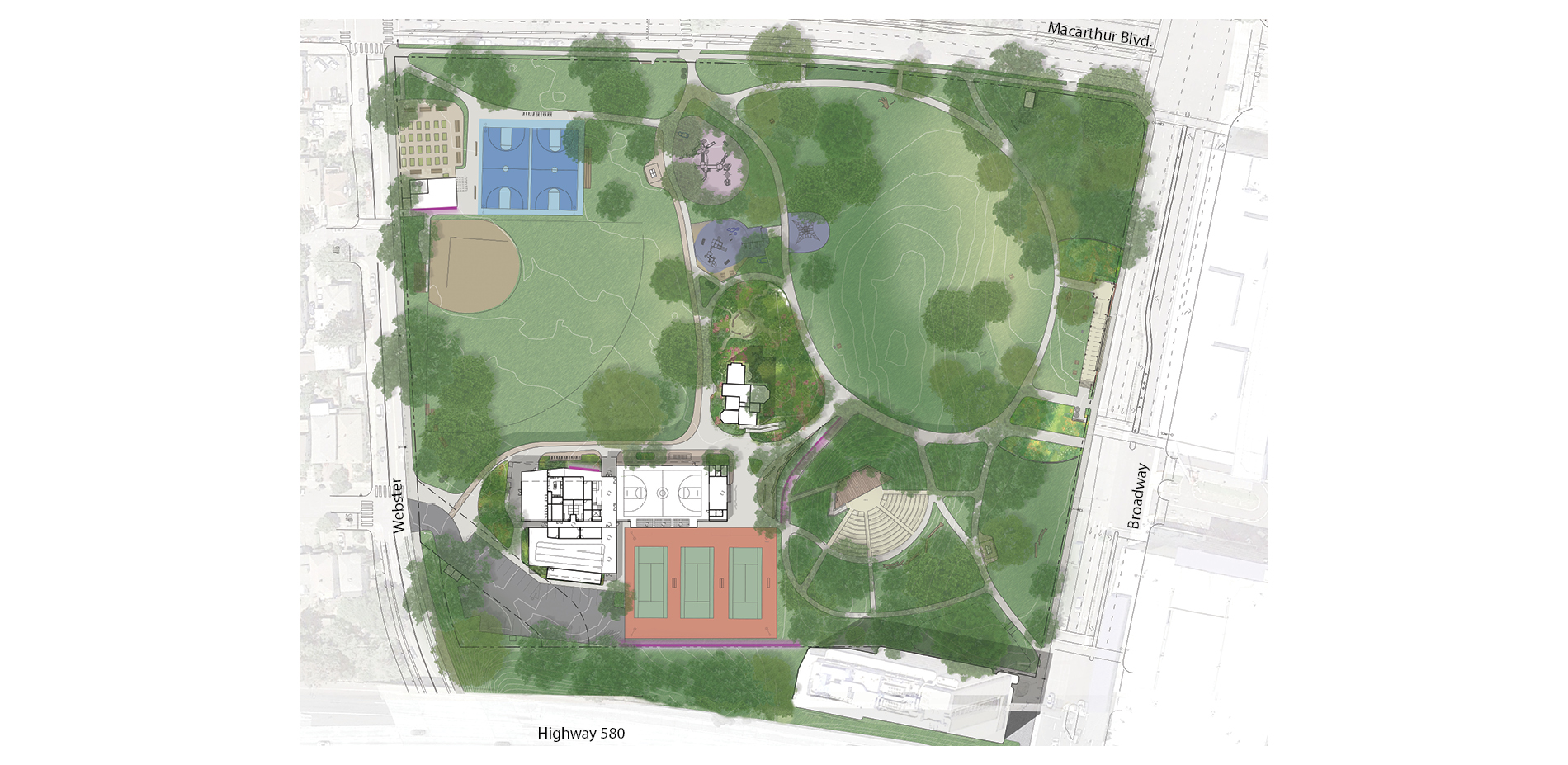

Mosswood Park, located in Oakland, California, is a beloved community park. The Mosswood Park Master Plan began as a deep dive into a more complete history of the park that broadened the areas of historic interest, originally limited to the historic Carpenter Gothic J. Mora Moss House and Estate. This wider reconceptualization of history included pre-Mr. Moss’s ownership, numerous important events and community activities which occurred in the park throughout the 1970s, among other histories. The design team researched the history of the park beginning with the Ohlone people and the importance of the ecology of the creek that is now covered over. The team also reviewed the post wartime parks and recreation history at the site and the original conception of a community center at the Junior Center for Arts and Science. The center served all kids and had a curriculum focused on creativity, a precursor of today’s STEM and STEAM programs. Despite disruption of the park with the construction of highway 580 in 1954, Mosswood Park remained an important center for the African American community who exhibited resilience as gradual disinvestment in the neighborhood occurred.

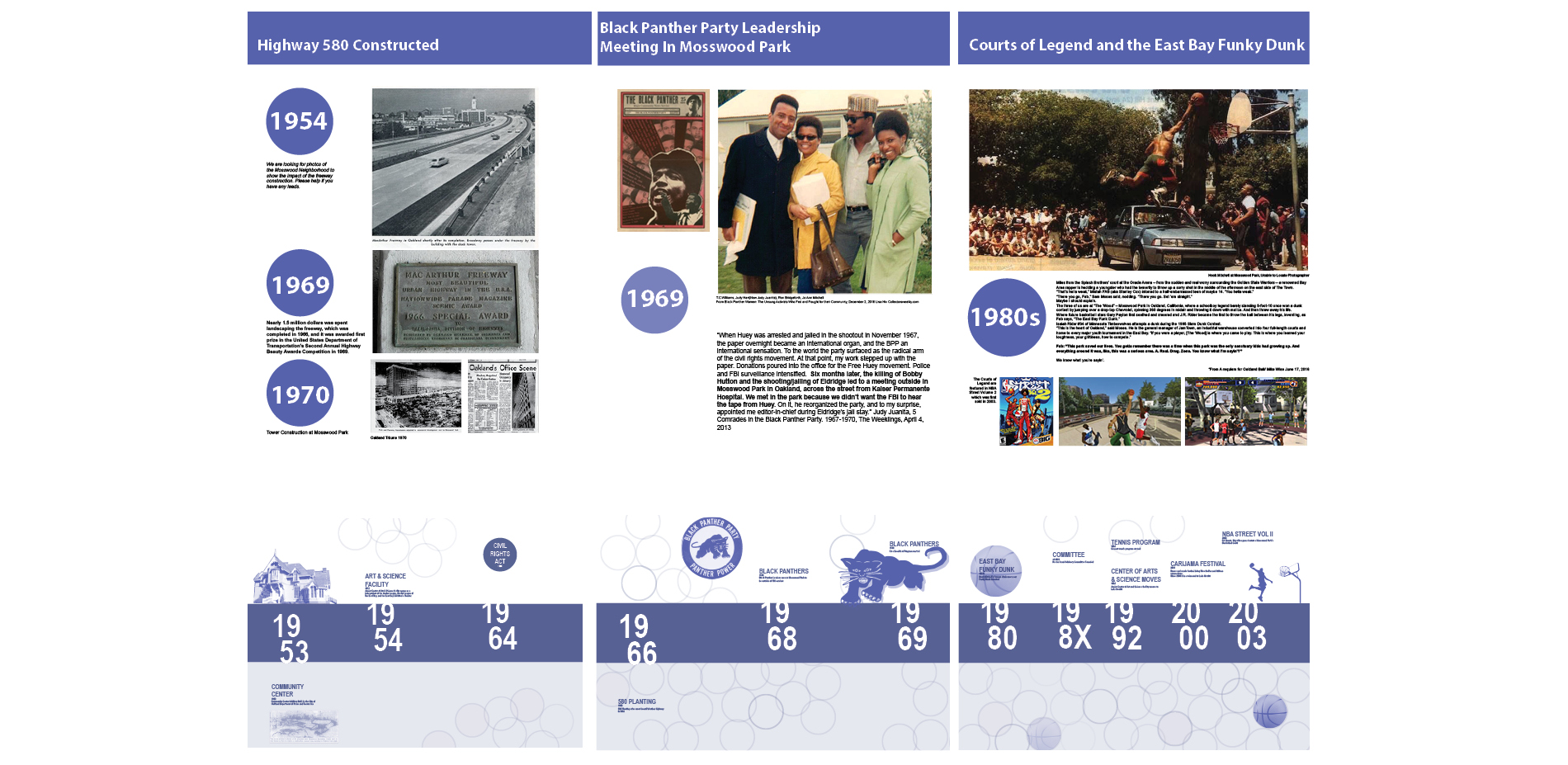

This deep dive into many eras of history and many different stories of the park resulted in a framework where the “Historic J. Mora Moss House” and the famous basketball Courts of Legend were both considered of equal importance in park history and numerous other smaller social events that together show social resistance and resiliency by marginalized groups were also considered of great value.

Our team’s research reinforced the idea that although gentrification has changed the racial and economic make-up of immediate neighbors to the park, the site remains a place to protect, strengthen, and center culture for many black, indigenous and people of color communities (BIPOC) and as such, the propinquity of new generally wealthier and whiter neighbors would need to be balanced in planning for the future. Therefore, one of the goals of the Master Plan community engagement process was to give a voice to the older generation of Mosswood residents and their families, particularly the Black and African American communities that have a deep connection to the park but have been displaced over recent years to other parts of Oakland.

Community Based Design

A year-long process of workshops and community engagement was implemented by a grant application. The schedule necessitated moving quickly and required the community’s willingness to engage often during the year, a keystone to the success of the outcome. Prior to the start of the workshops, the design team attended events that extended a more personal invitation to marginalized groups. A total of six workshops were led at the temporary community center within the park and nearby Studio One Art Center.

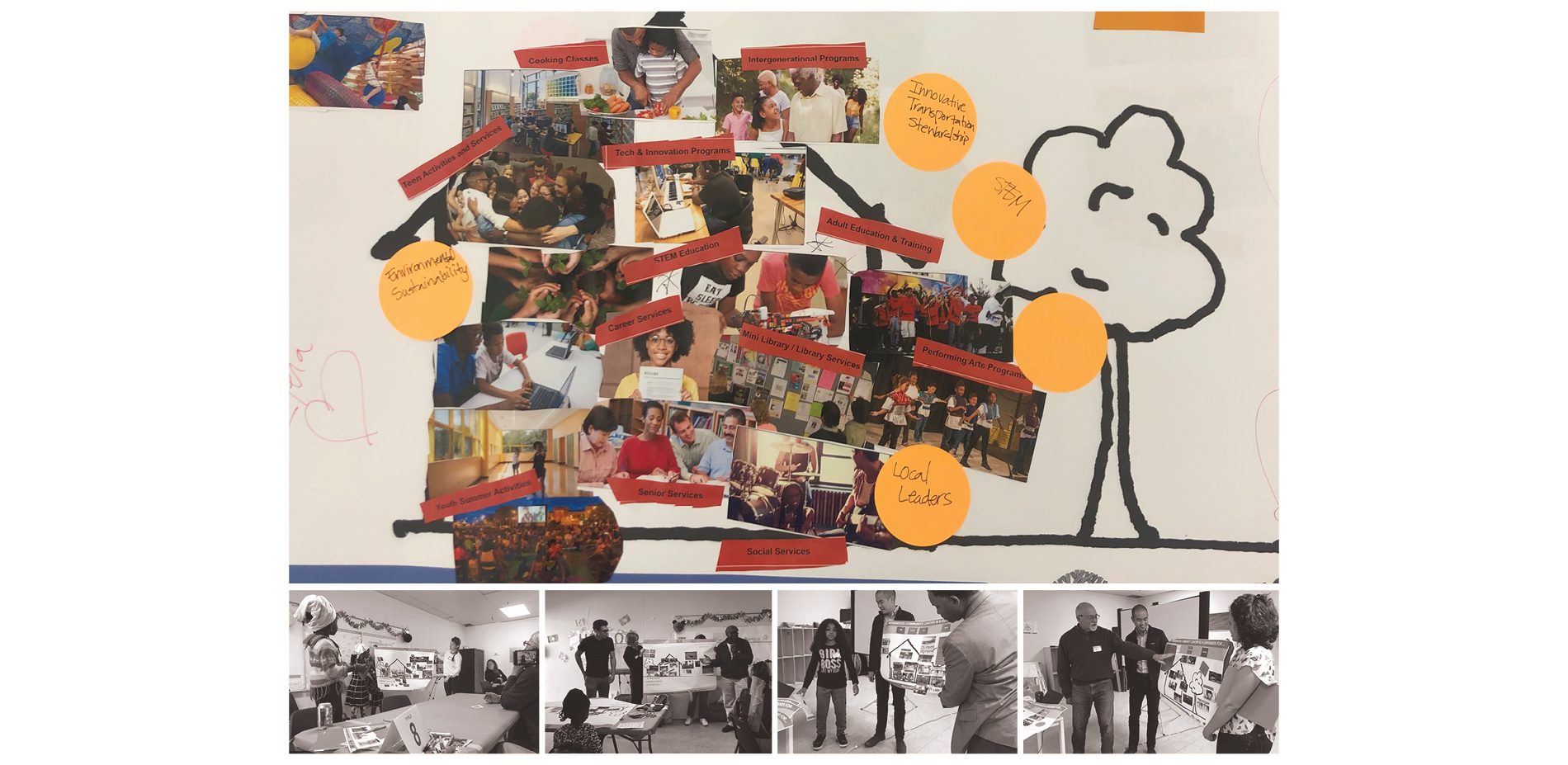

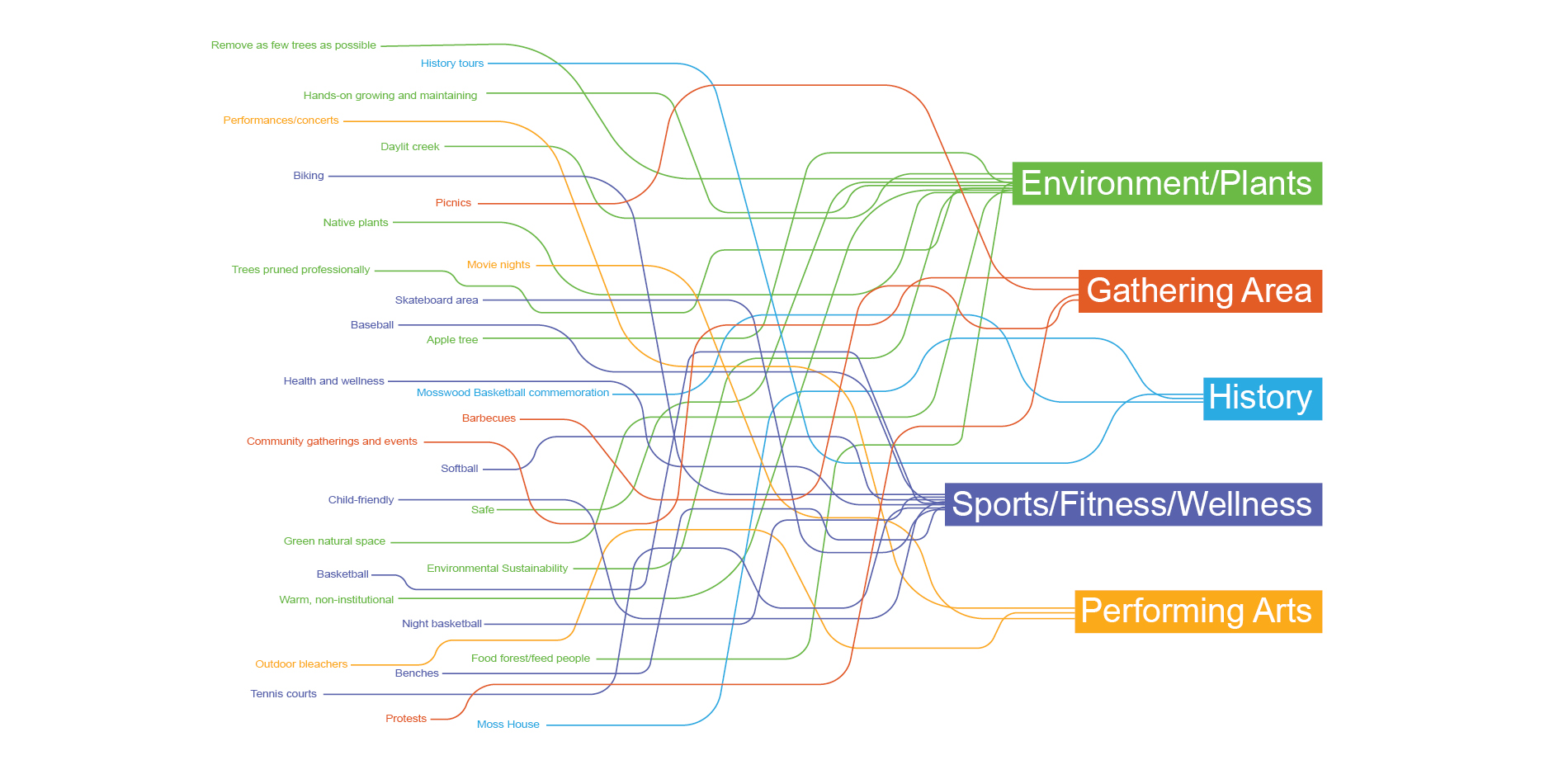

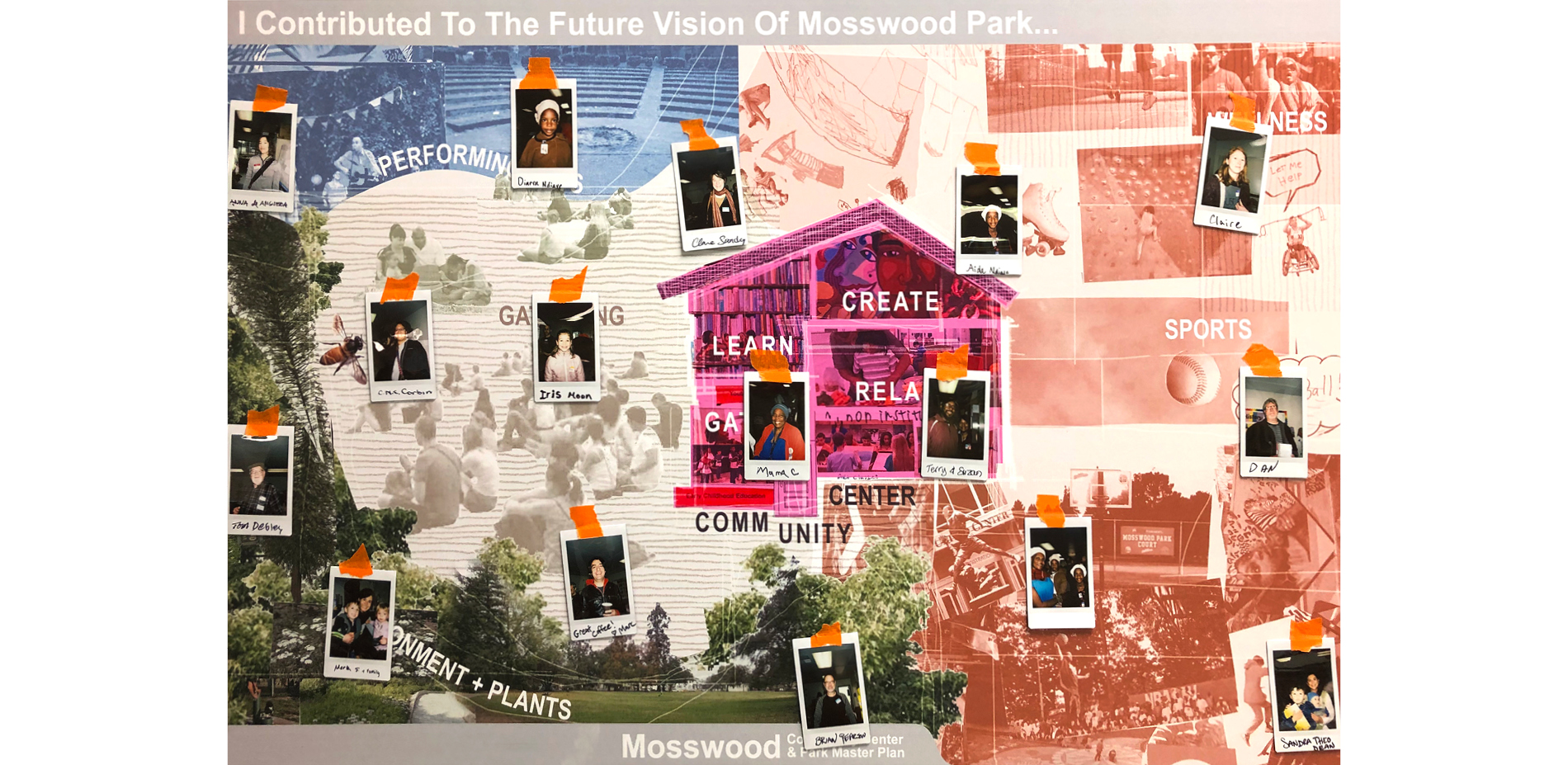

Developing high quality graphics for communication with the public was one way the design team expressed respect for the community members. The design team created a timeline which they called “The Incomplete History of Mosswood Park” that documented many different moments in the history of the land. The graphic included a board for ‘future visions of the park’ at the end of the workshops where community members expressed their hopes and dreams and imagined a future they would want to see at the park. This collective imagining of a shared future was a starting point for understanding what was working and beloved in the park, what was missing, and what could be changed.

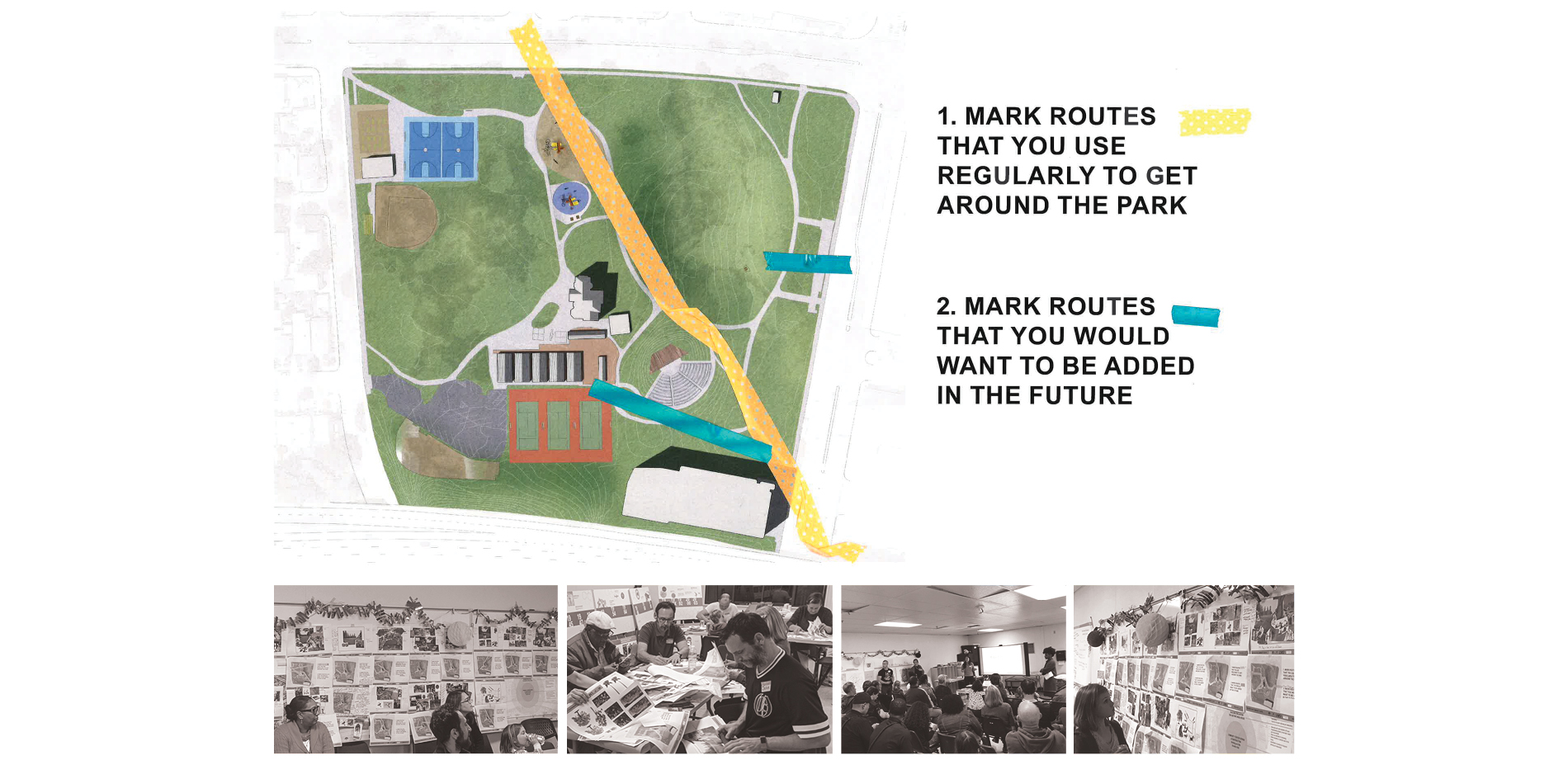

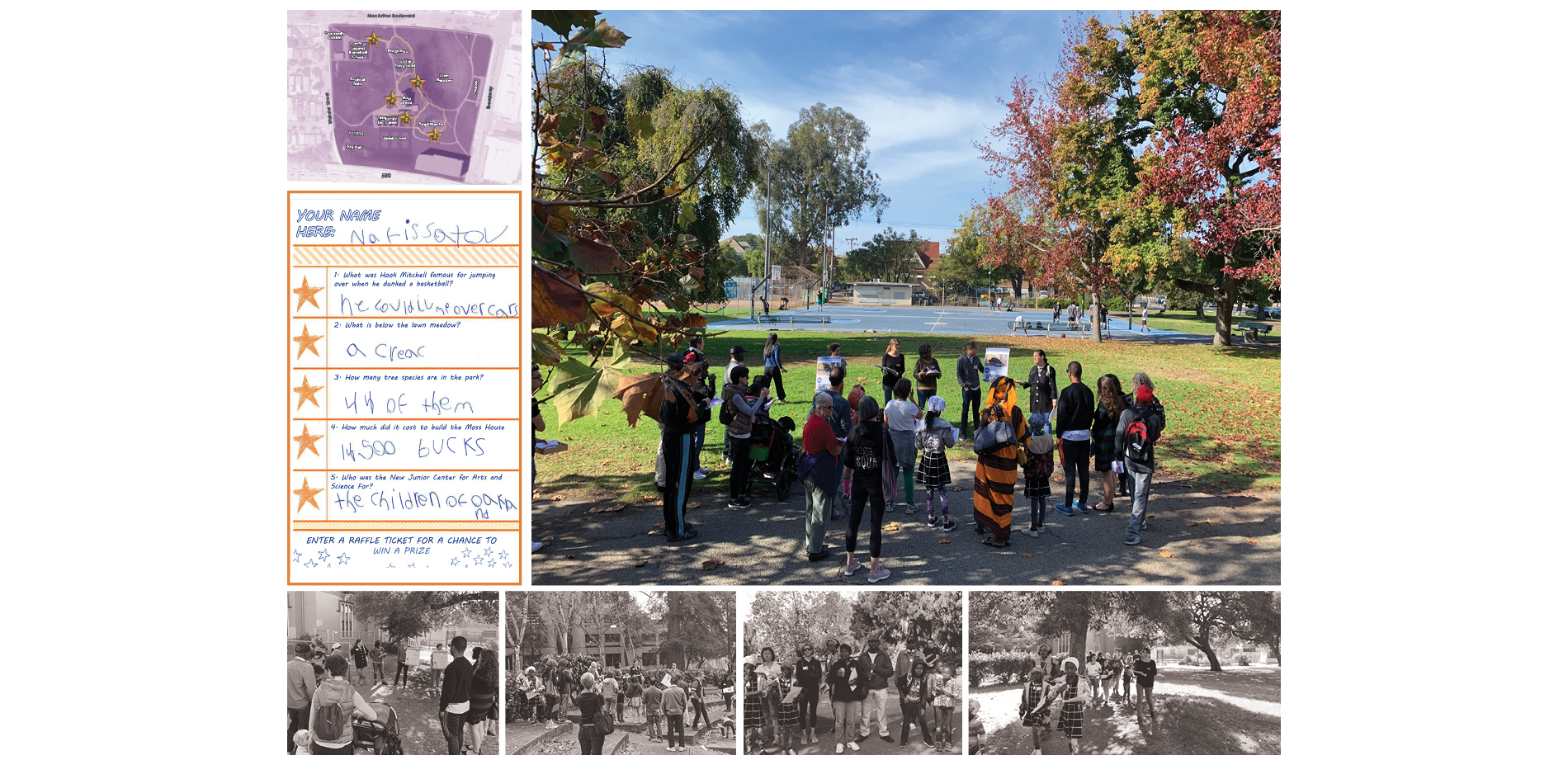

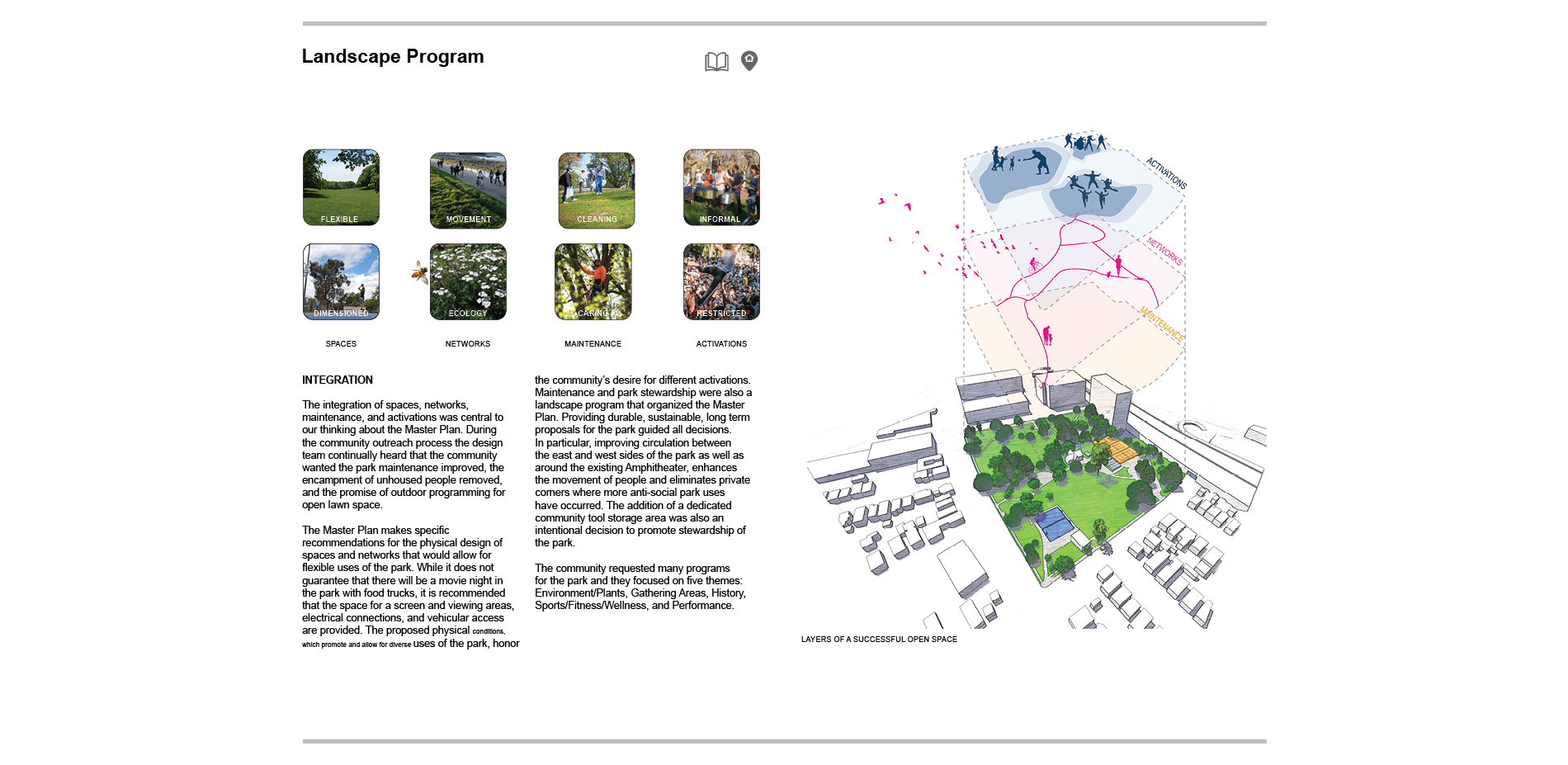

Tools for gathering ideas for the park’s design and a deep understanding of the site were created in numerous formats including: mapping with tape, individual collages of scenes in the park, group collages showing what people wanted to see at the new community center and surrounds, and site walks where spontaneous sharing of memories were layered over the design team’s recounting of important site stories they had learned about while researching the park’s history.

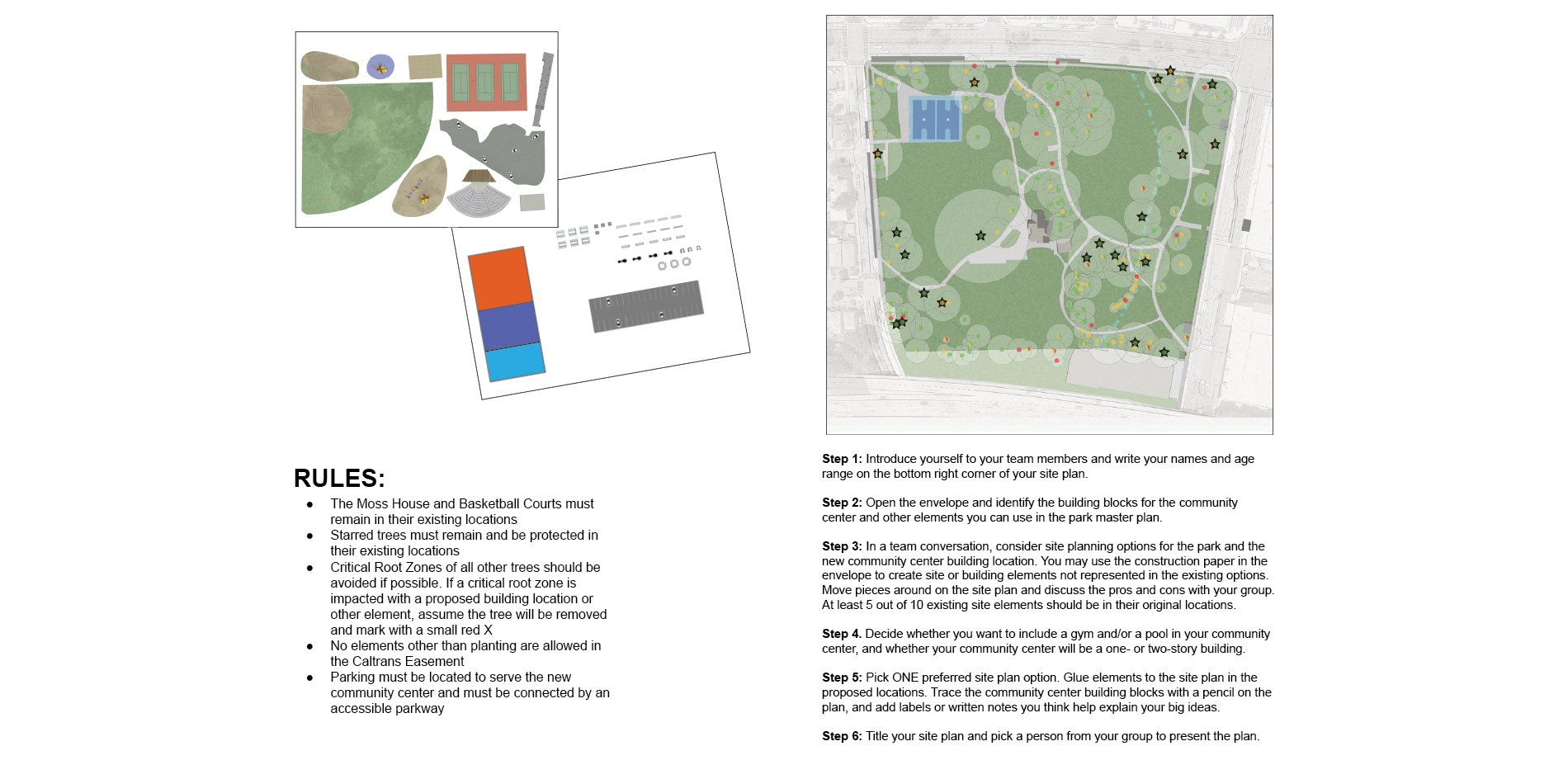

Synthesizing community ideas into graphics, the design team also provided their expert knowledge about the trees, geotechnical conditions of the site, and the sizes of different site elements the community wanted in the park. A design challenge (with a few rules to protect important historic resources, including the mature trees) was explored by small teams. Wood blocks carefully cut and sanded from the most common species of trees found at the park—Oak, Redwood, and Catalina Cherry--were used as scaled building blocks that could be placed on site plans for study during discussions.

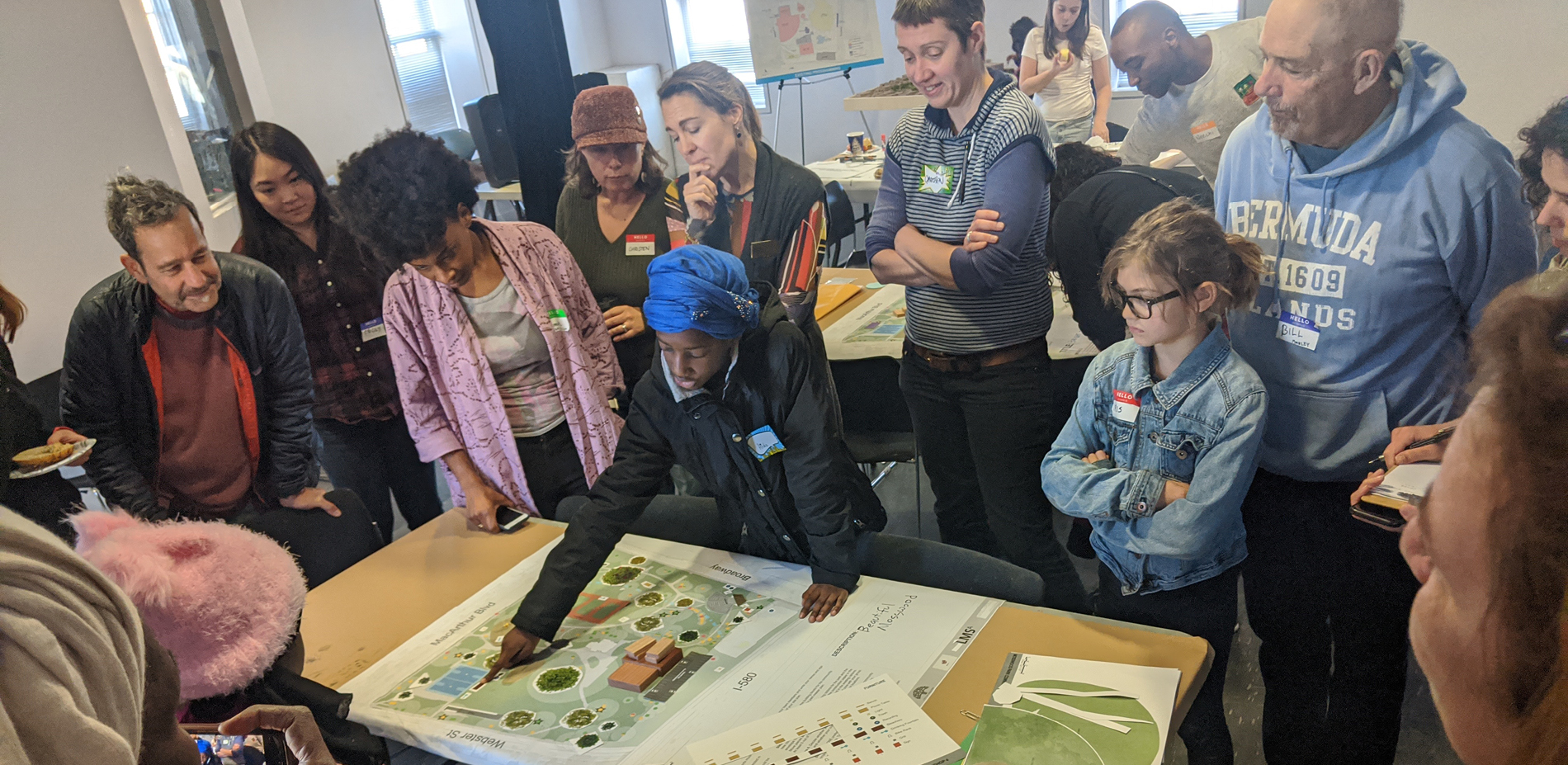

Three primary locations for the new community center emerged from the community’s ideas and the design team refined each of these locations into schemes that further explored overall site organization. The community provided input on these three schemes which were presented in physical models, digital model views, and site plans. Stations for sustainability, history, and other important topics were set up for input on each of the three schemes.

With remarkable consensus, a single location emerged from review of the three design options and was subsequently incorporated into the recommendation for the master plan. The final design was presented at a final workshop and posted to the city website for review. All comments were then addressed and the final master plan was published and approved in February 2021 by the Oakland City Council.

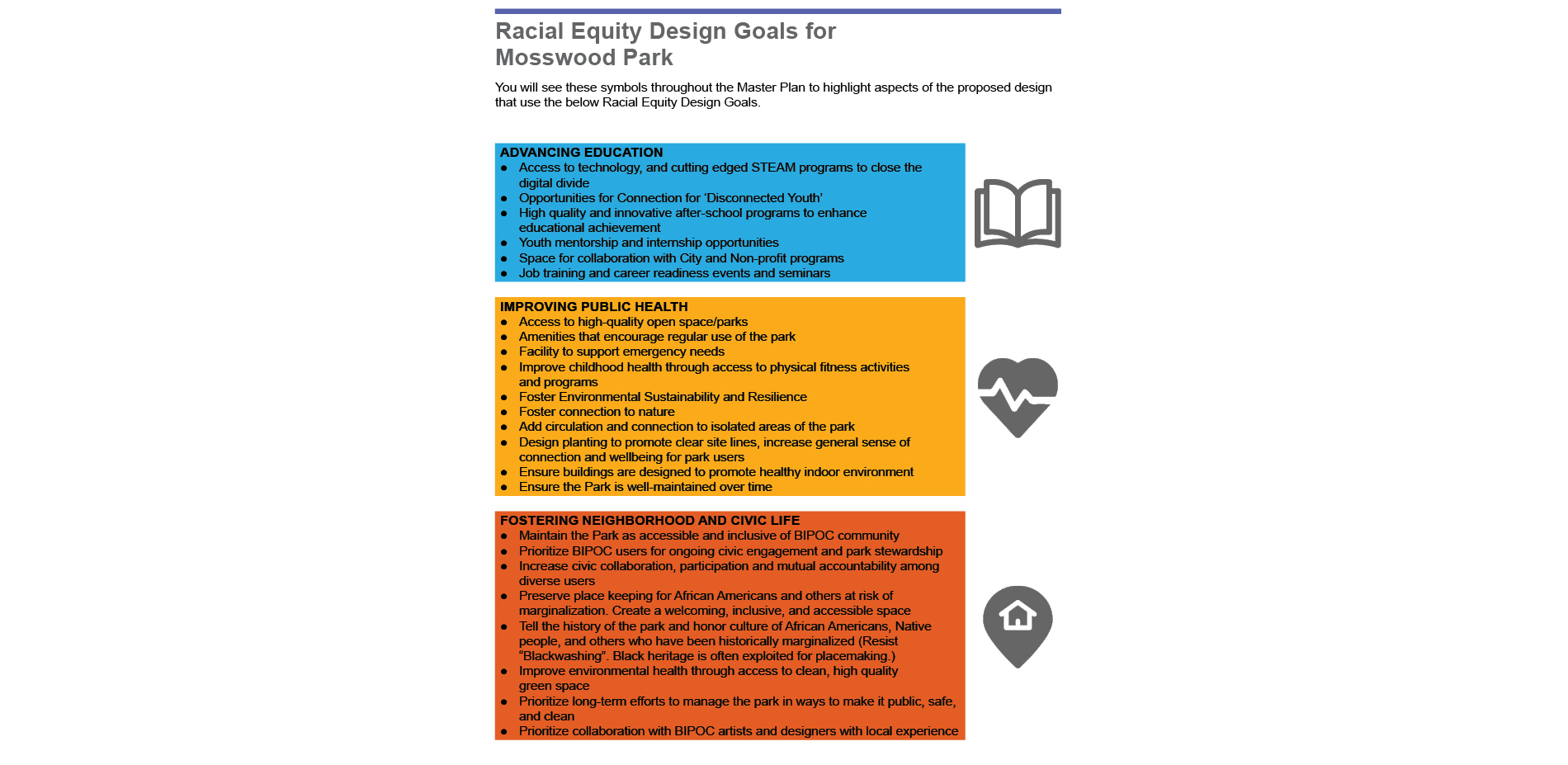

Racial Equity Design Goals

Working within a historically black community, with the knowledge that safety for black, indigenous and people of color communities (BIPOC) in public space has been severely lacking for a long time and is overdue to be addressed, the City of Oakland and the design team made a commitment to act on closing these disparities in the Master Plan document. The built environment has the unique responsibility to manifest values and close disparities by broadening windows of opportunity for BIPOC communities whose voices have been historically silenced and minimized by racism. The City of Oakland’s ‘Geographic Equity Toolbox’ prioritizes neighborhoods based on concentrations of people with demographic factors determined to have experienced historic and current disparities. The design team and the city used the criteria defined in the ‘Oakland Equity Indicators Report’ to evaluate equity at the park across six themes: Economy, Education, Public Health, Housing, Public Safety, and Neighborhood and Civic Life. Based on an analysis of the park users and context, three tranches of racial equity design goals for Mosswood Park were identified. The community values that were heard in many surveys and workshops matched these goals. Within the Master Plan document, there are symbols for Advancing Education, Improving Public Health, and Fostering Neighborhood and Civic Life. Elements of the Master Plan were identified that particularly supported these goals so that in the future if decisions needed to be made to bring a project on budget or otherwise limit the scope, the elements that supported racial and equity design goals would be prioritized.

The team continues to improve the design, ensuring the success of project goals as they develop the design for the Phase One Community Center.