Climate Positive Design

Honor Award

Research

The benefits of landscape architecture to air quality have long been touted, but ways of quantifying how a design can be carbon-positive have eluded the profession. Through analysis of 20 case studies, a team of landscape architects has developed a design toolkit illustrating more than 80 carbon positive landscape intervention strategies. A companion application allows instant calculation of carbon impact based on quantity and variety of plants input in users’ designs, to enable better understanding of efforts toward reducing emissions and increasing sequestration across a project. These kinds of real-time feedback will be crucial for the profession, and for the world, to avoid the irreversible climate damage we will encounter without meaningful reductions in emissions.

- 2020 Awards Jury

Project Credits

Pamela Conrad, CMG Landscape Architecture, Primary Research Director

CMG Landscape Architecture, Primary Sponsor

Kevin Conger, Willett Moss, Chris Guillard, Jamie Phillips, Rayna deNiord, Greg Barger, Eustacia Brossart, Jamie Yousten, Kelsey Wakefield, Wesley Cogan, Ilia Savin, Lauren Bergenholtz, Kate Lenahan, Nahal Sohbati, Alexandra Zahn, CMG Landscape Architecture, Design Team

Edan Weis, Aspect Studios; Cameron Nimmo; Larry Lague, Google , Technology Partners

Lauren Peters, Salesforce; Anne Donnard, Emerson Blue; Tyler Maisano, Tract; Chris Hepner, Paulina Tran, Pooja Desai, CMG , Art Direction/Graphic and Web Design

Vaughn Rinner, FASLA; Nancy Sommerville, Hon. ASLA; Colleen Mercer-Clarke, CSLA/ LACF/ IFLA; Barbara Deutsch, LAF; Martha Schwartz Partners; 2018-2019 LAF Fellowship Cohort and Facilitators: Lucinda Sanders, OLIN; Laura Solano, MVVA, Advisory Partners

Antoinette Marty, Data Analysis

Kristen DiStefano, Atelier 10; Prateek Jain, Atelier 10, Research Partners

Project Statement

The global community has declared a climate emergency due to unprecedented levels of carbon dioxide filling the atmosphere with devastating, visible effects. While landscape projects produce emissions, they can also contribute to the solutions through tree and plant carbon sequestration. However, without a way to measure, their impacts remain unknown. Beyond the challenge of measuring, the question looms whether projects can be climate positive by sequestering more carbon than they emit.

In 2019, Climate Positive Design launched with the mission to improve the impact of built landscapes through collective action. The initiative grew from the inquiry of one to a multi-disciplinary international collaboration reaching nearly half the countries in the world in less than a year. The research-based Pathfinder application and Climate Positive Design Challenge guide designers to reduce carbon footprints while increasing carbon sequestration within their projects.

While created by landscape architects, the online resources are applicable and accessible to other disciplines, municipalities, and the everyday gardener. Case studies and project entries to date show that we can indeed be part of the solution.

Project Narrative

TIME IS OF THE ESSENCE

In 2019, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warned that 10-years remains for aggressive reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations necessary to prevent a 1.5-degree Celsius temperature increase that will cause irreversible damage to our planet and society if left unchecked.

Architecture 2030 reports that the urban built environment is responsible for 75% of annual GHG emissions. Of those impacts, 36% come from outside buildings. While landscape architecture projects contribute emissions, they also contain trees and plants that take carbon dioxide – the primary GHG – out of the atmosphere.

Landscape carbon systems are complex – they include embodied carbon emissions from material manufacturing and transportation and operational carbon emitted over time through maintenance and fertilizers, but they also sequester CO2 from the atmosphere and store it in trees, plants and soil. Methods to calculate architectural carbon have been developed over the last decade such as Athena, Tally, or One-Click LCA, but due to the organic complexity of site design, the landscape architecture profession has not been able to actively measure, track, or improve the carbon impacts of its collective work.

Can landscape architecture projects sequester more carbon than they emit and contribute to climate positive action?

METHODS

Landscape architects led the research component of this initiative and collaborated with an environmental consultant to advise on industry standards. The primary research methods are as follows:

1. Literature Review: Analysis of seminal publications on climate science, carbon sequestration and storage, embodied carbon of materials and operational emissions.

2. Market and Industry Standard Research: Identifying current climate action efforts of related disciplines, guidance, challenges, standards, rating systems and practices.

3. Case Studies: Testing strategies to reduce emissions and increase carbon sequestration on built projects to better understand which strategies provide the greatest impact.

RESULTS

DATA REPORT: METHODOLOGY, DATA SOURCES AND METRICS

A comprehensive literature review provided a foundational understanding of climate science and its relationship to the built environment. As the IPCC 1.5-Degree Report and “Drawdown” by Paul Hawken were authored during this time, both provided clarity into the urgency of the situation and insight into developing metrics for possible solutions.

The Athena Impact Estimator is the most comprehensive open source of embodied carbon for materials related to the landscape field. The Global Warming Potential (GWP) CO2e value is the main data point, which can also be extrapolated from international Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs).

The US Forest Service sequestration data provided in iTree was used to determine sequestration rates for a range of species varying in size, location and foliage type. The sequestration data is based on planted trees in urban/sub-urban areas rather than that of rates from natural areas. Regional rates vary significantly due to number of growth days per year and set the priority over species type due to a higher variability.

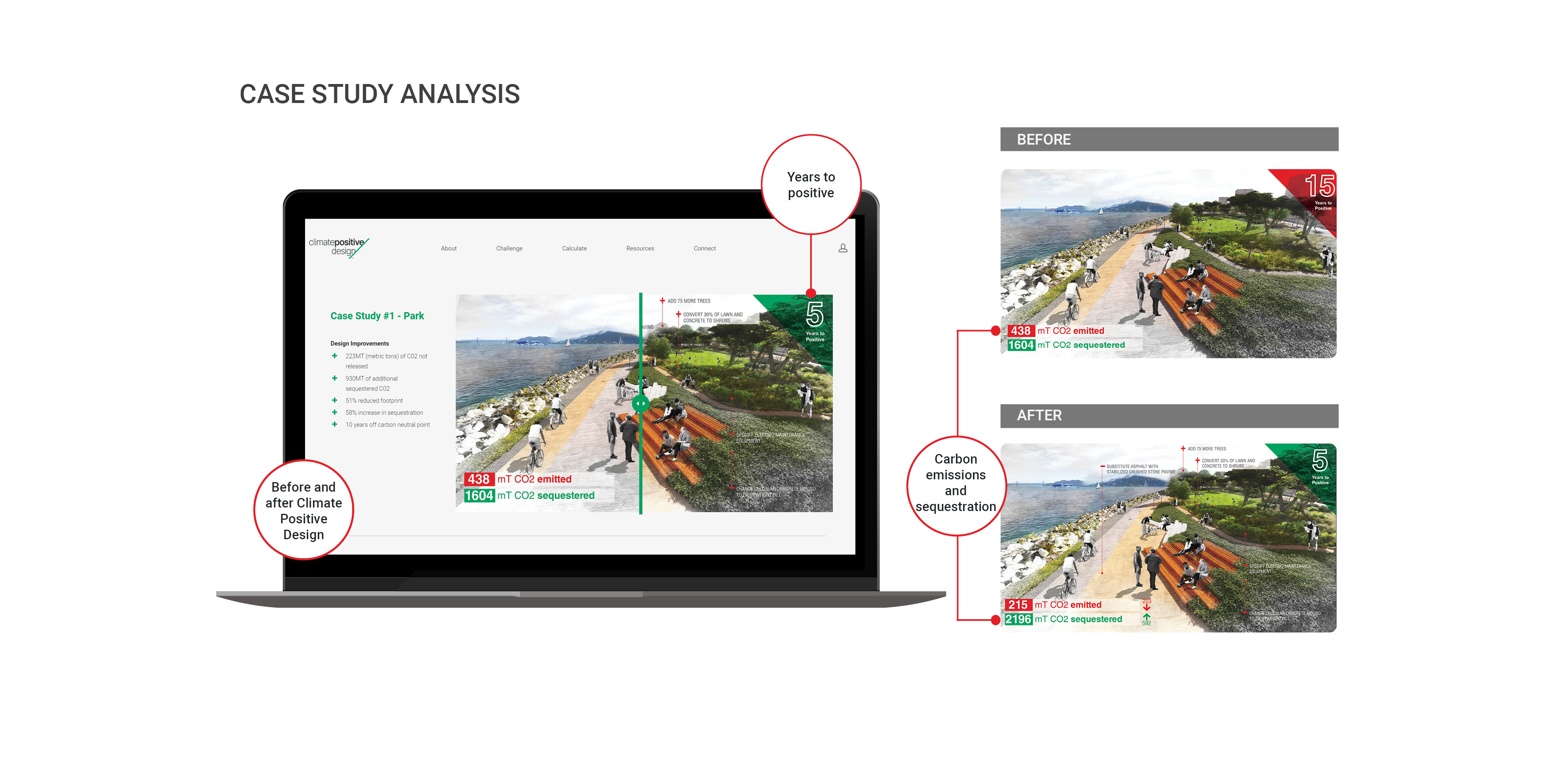

The team performed in-depth case study analysis on over 20 built projects. This included the evaluation of embodied carbon, operational carbon, carbon sequestration, along with the years required to offset project emissions (i.e. years to positive). Through this analysis, project adjustments were made without significantly changing the design while improving carbon impacts. These observations and calculations are recorded in the Data Report.

TOOLS, GUIDANCE AND RESOURCES

The research showed that there is no landscape “magic bullet” for climate change but clearly indicated the need for a carbon calculator specific to landscape architecture.

After evaluating the climate action progress of other disciplines and organizations, understanding performance metrics strategies and engaging the profession at large, Climate Positive Design was created. The website houses a range of tools, guidance and resources, including a Design Toolkit that outlines over 80 different strategies for improving carbon impacts of landscape projects.

Climate Positive Design Challenge

The case studies illuminated that aggregated small changes add up to significant carbon footprint improvement without significantly changing project design or quality. It became clear that urban projects, such as plazas and streetscapes, have a higher carbon footprint per square foot than that of “greener” projects such as parks or campuses that have less program and inherently more planting. Accordingly, the years to offset or “years to positive” was higher for the more urban projects.

Several Design Challenge options were reviewed by Advisory Partner organizations and the agreed upon methodology was to focus on “years to positive” (YTP) as this metric requires both reducing emissions and increasing sequestration. To determine targets for the Climate Positive Design Challenge, an average of the case study projects YTP was selected. For parks, gardens, campuses the YTP target is five years and for streets and plazas the target is set at 20 years.

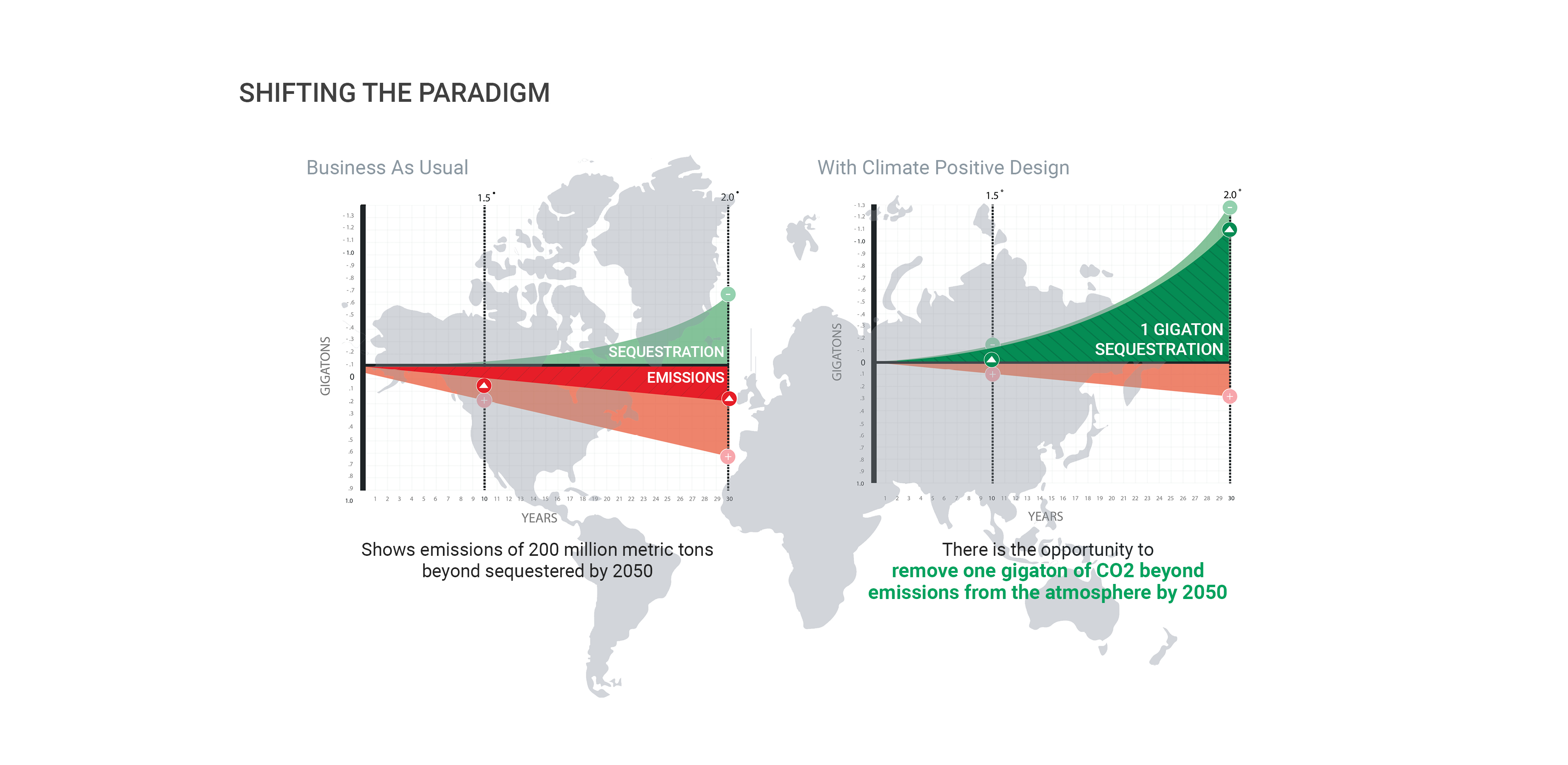

Using unchanged case study project data, or “business as usual”, and extrapolating that to the global community of approximately 75,000 landscape architects, projections show that projects collectively emit more carbon than they sequester. However, by meeting the goals of the Challenge, the results would instead show projects sequestering more carbon than emitted by 2030 and extracting roughly one gigaton of CO2 out of the atmosphere by 2050 beyond emissions. This impact would fall within the top 80 solutions listed in “Drawdown” by Paul Hawken, that when implemented collectively over the next 30 years will reduce GHG emissions on an annual basis and reverse global warming.

The Pathfinder

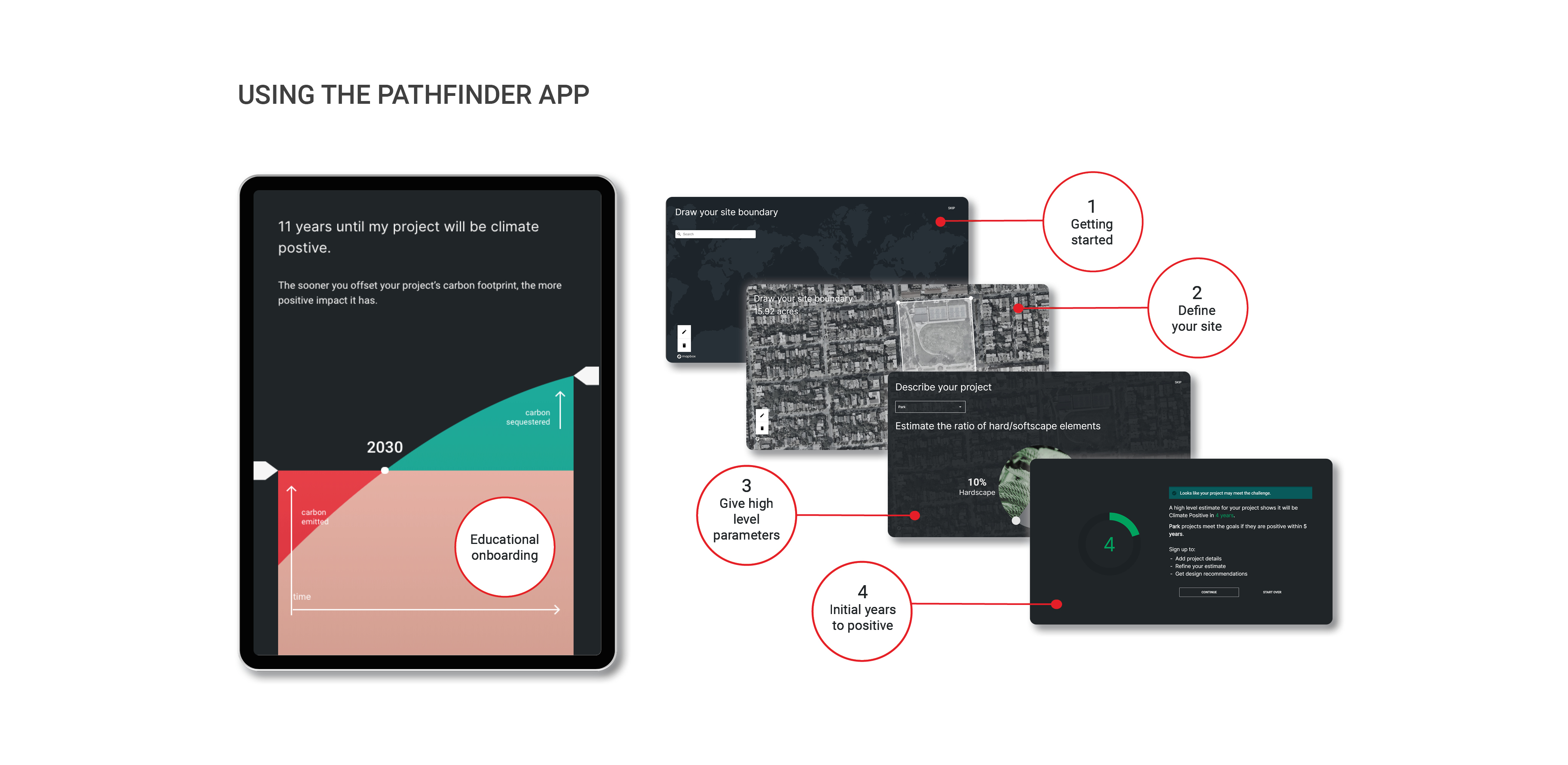

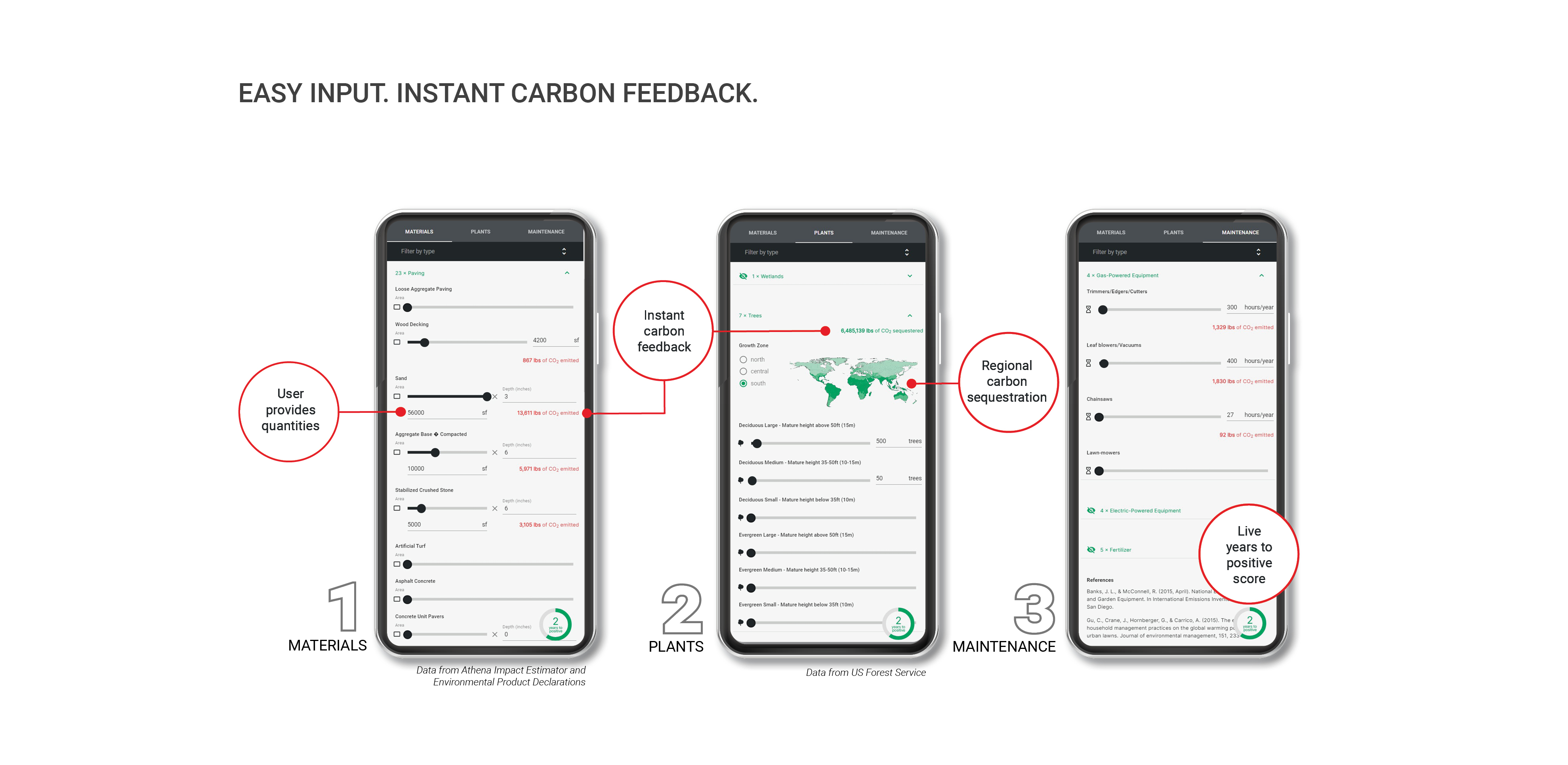

To ensure the greatest possible success in the development of a landscape carbon calculator, a survey that was conducted of over fifty landscape architects reported that for them to incorporate carbon analysis into their work, it would: 1) Need to be easy; 2) Integrate with their project work-flow/process, and 3) Show feedback that it would make a difference.

To meet user expectations while maintaining flexibility to evolve over time and to have a global reach, the beta version of the carbon calculator transformed into a web-based application called the Pathfinder.

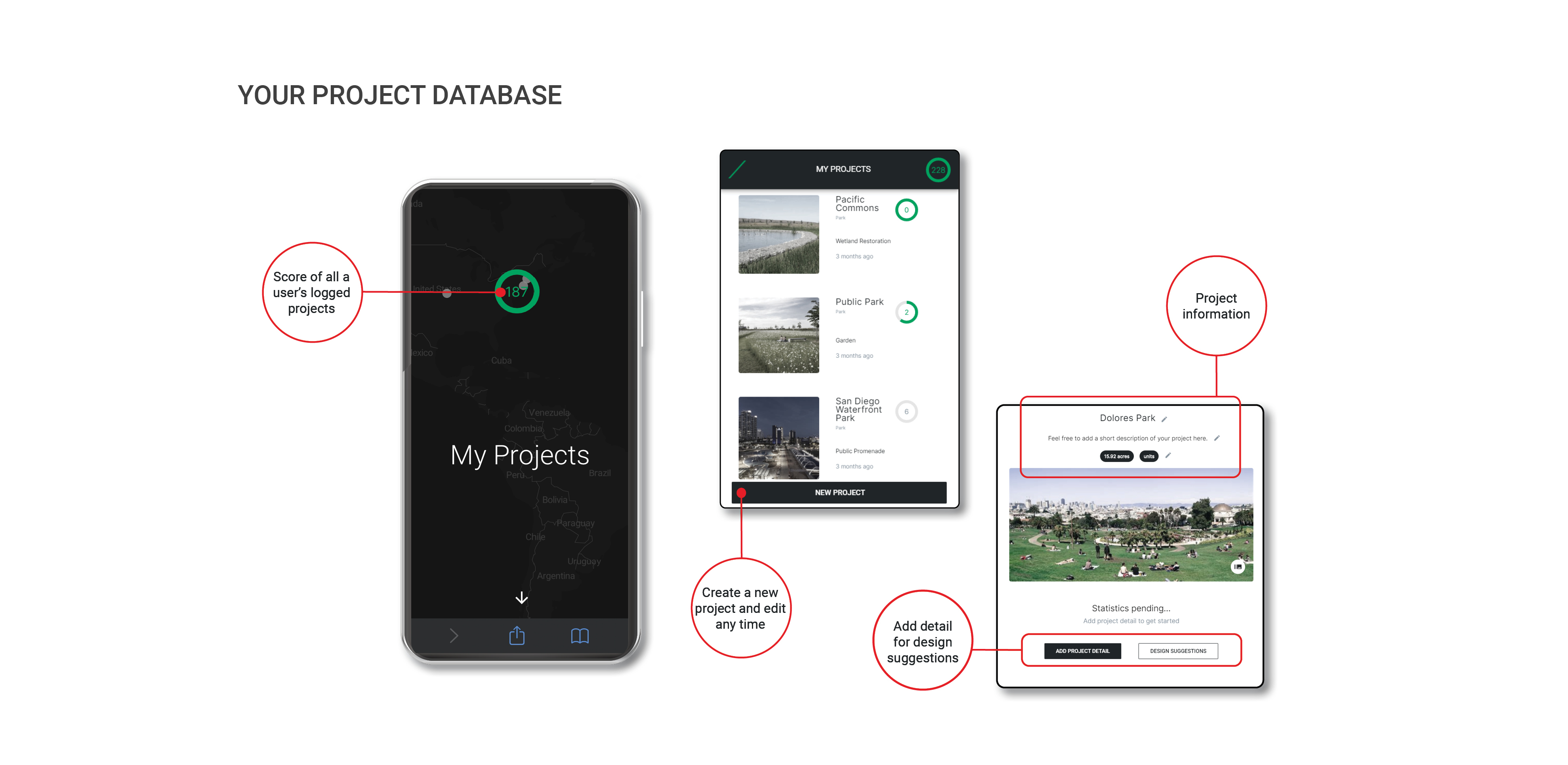

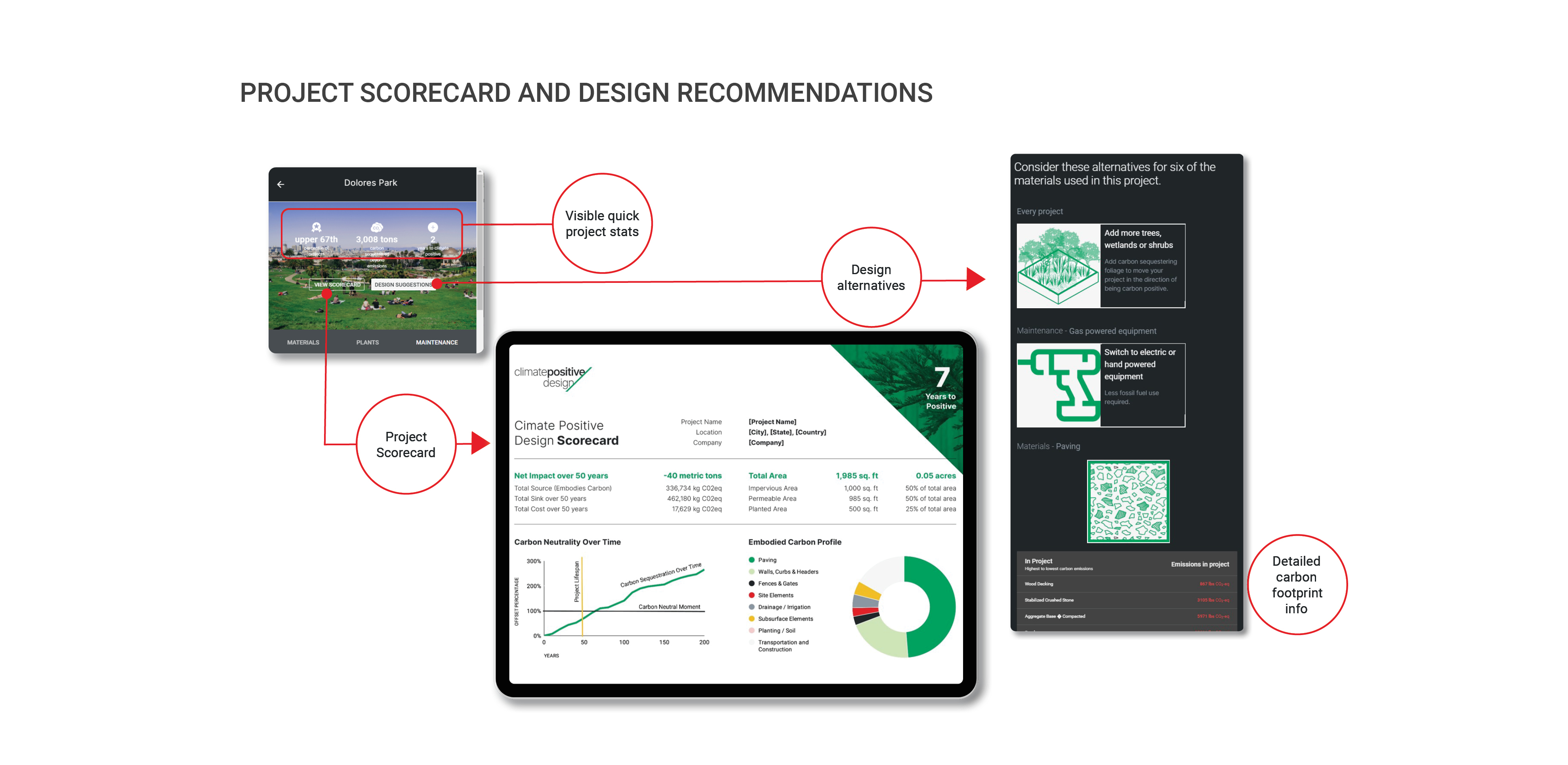

The app features educational onboarding and a homepage for each user, or company, where projects can be created or edited at any point in time. Users enter quantities for materials, plants, or maintenance plans and receive instant feedback on carbon emissions, sequestration, and their YTP or Climate Positive Score. A scorecard provides detailed stats that can be plugged directly into Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) and project specific design suggestions help guide users toward improving their project’s impact.

Through the use of the Pathfinder, designers can meet the goals of the Climate Positive Design Challenge by reducing carbon emissions and increasing sequestration.

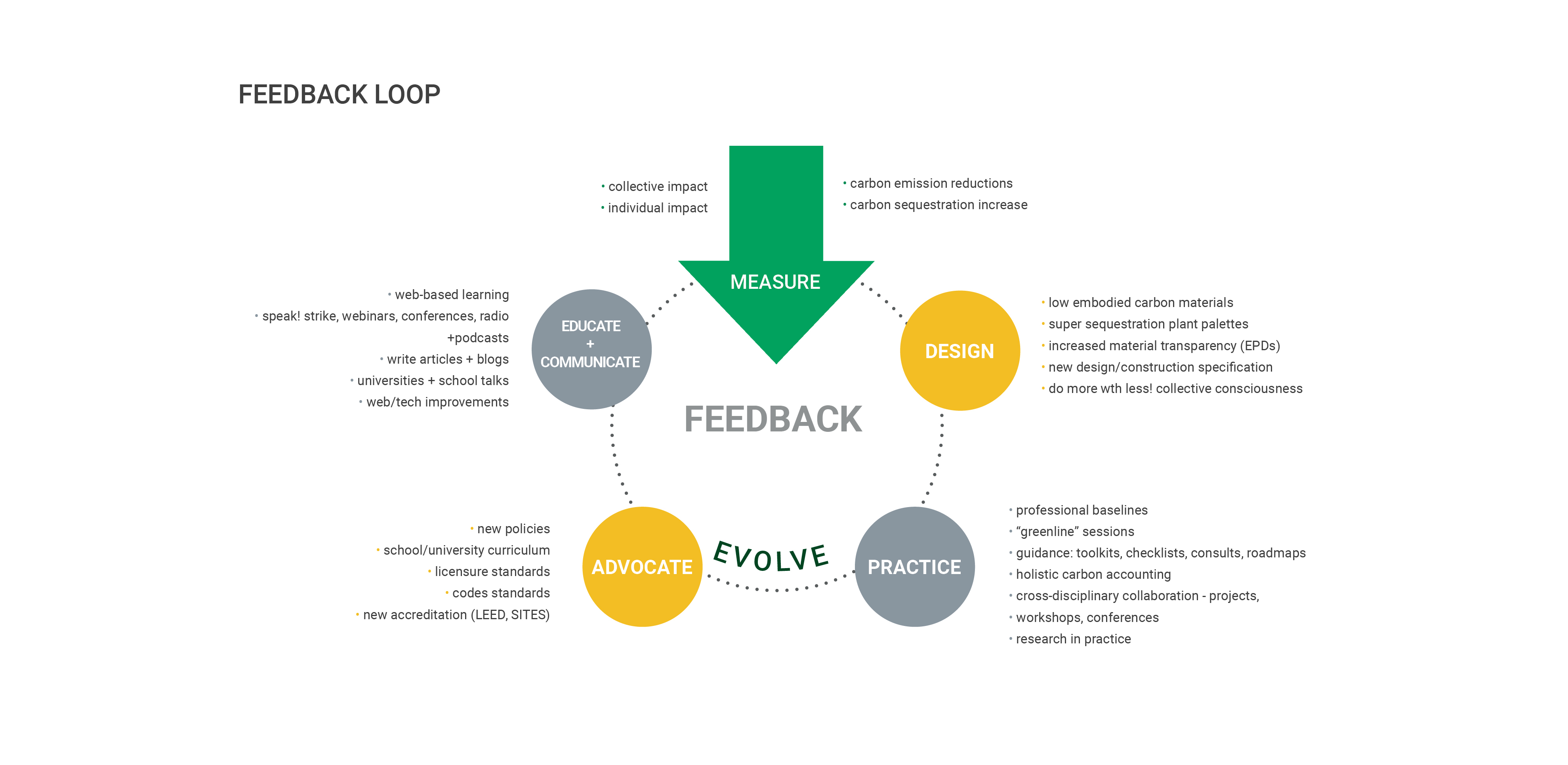

SIGNIFICANCE

By measuring carbon impacts collectively for the first time as a profession, landscape architects can initiate a feedback loop that informs design and the resources needed to evolve our practices. By requesting EPDs on products and materials, we will collectively signal the importance of carbon footprints to our suppliers. Information collected will inform new policies, standards, what we teach, and how we communicate.

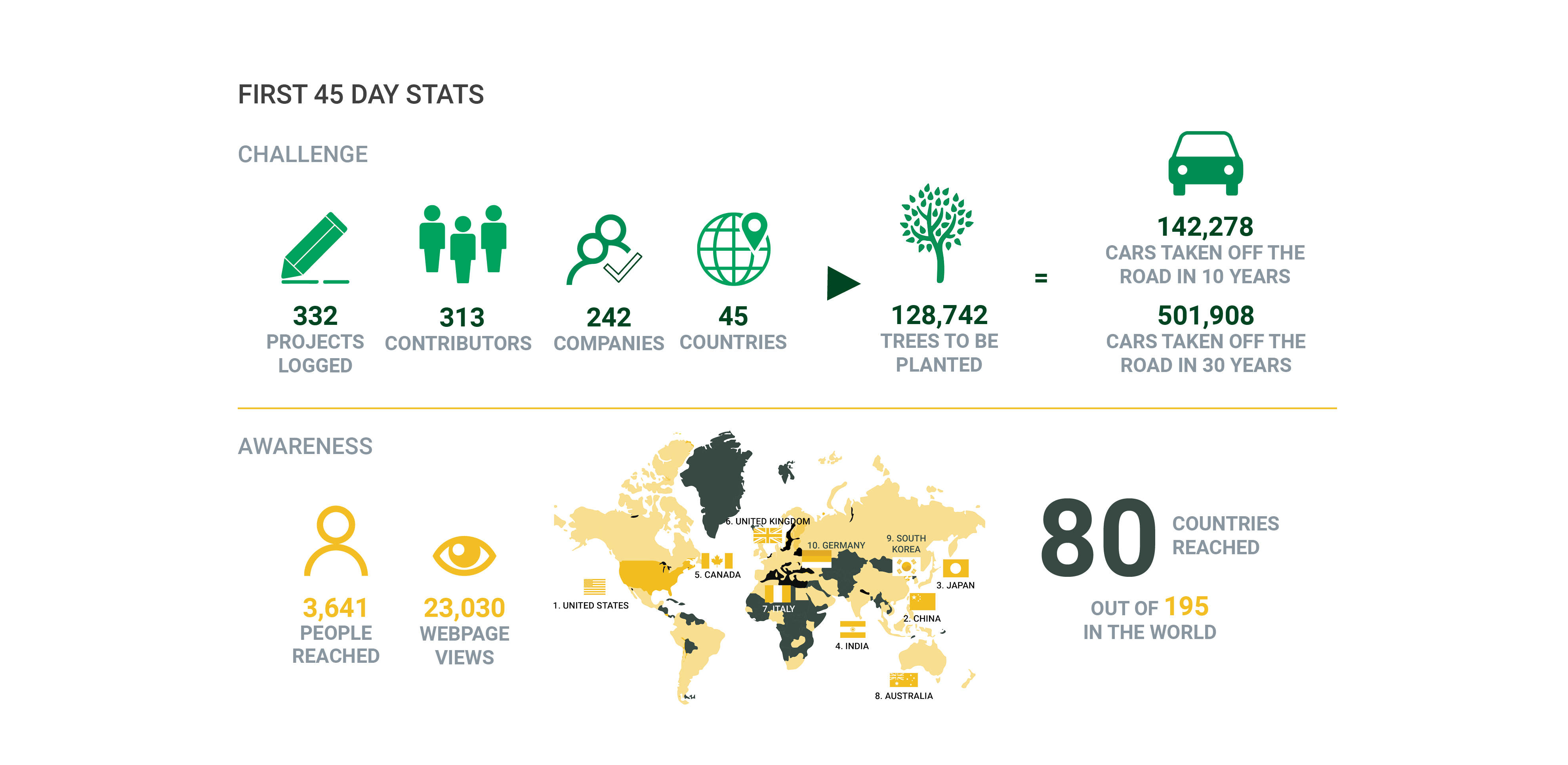

Within the first forty-five days of the launch, initiative awareness reached at least 80 countries and thousands of people. Over 330 projects were logged by 313 contributors - reduction impacts equivalent of taking over 500,000 cars off the road in 30 years by planting close to 130,000 trees. Although initial participation shows a clear increase in awareness, research must be advanced to continue to improve the efficacy of these results – specifically advancements to better understand soil disturbance and more detailed sequestration rates for plant communities beyond tree species.

Additional enhancements to the application database are needed to ensure accuracy of the information collected in relation to meeting the Challenge targets that will be re-evaluated over time. Although the research initiative is still in its early stages, the potential impact appears promising that we can indeed have a Climate Positive impact, but this will only improve through the collective commitment from the profession.

The choice is ours to rise to the challenge – we’re all in this together.