The Invention of Rivers: Alexander's Eye and Ganga's Descent

Honor Award

Communications

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

Dilip da Cunha

On maps, rivers often appear simply as blue strokes through a landscape: a source and a course. But Dilip da Cunha imagines a far more mystical approach to these bodies of water: that they are traveling “rainscapes,” eschewing traditional distinctions of land versus water for a more widespread sense of wetness. Da Cunha traces the Ganges’ history from the time of Alexander to the present, inviting readers to reassess waterways in terms of the rainwater that fills them. This thinking, accompanied by plentiful illustrations, offers a fresh outlook on hydrology that may prove crucial in understanding and addressing a changing climate with more rain in the forecast.

- 2020 Awards Jury

Project Statement

The Invention of Rivers draws attention to the river as a product of design facilitated by a uniquely endowed line in a chosen moment of time in the hydrologic cycle. This line, imaged on maps, etched in the imagination, and enforced on the ground with regulations and constructions, has become a naturalized presence. Today, however, with the increasing frequency of flood associated with climate change alongside unwise development, the line of the river has come into sharp focus with proposals for levees, natural defenses, pumps, and retreat. These responses raise questions on where the line is drawn, but also on the separation that it facilitates. Is this separation found in nature or does nature follow from its assertion?

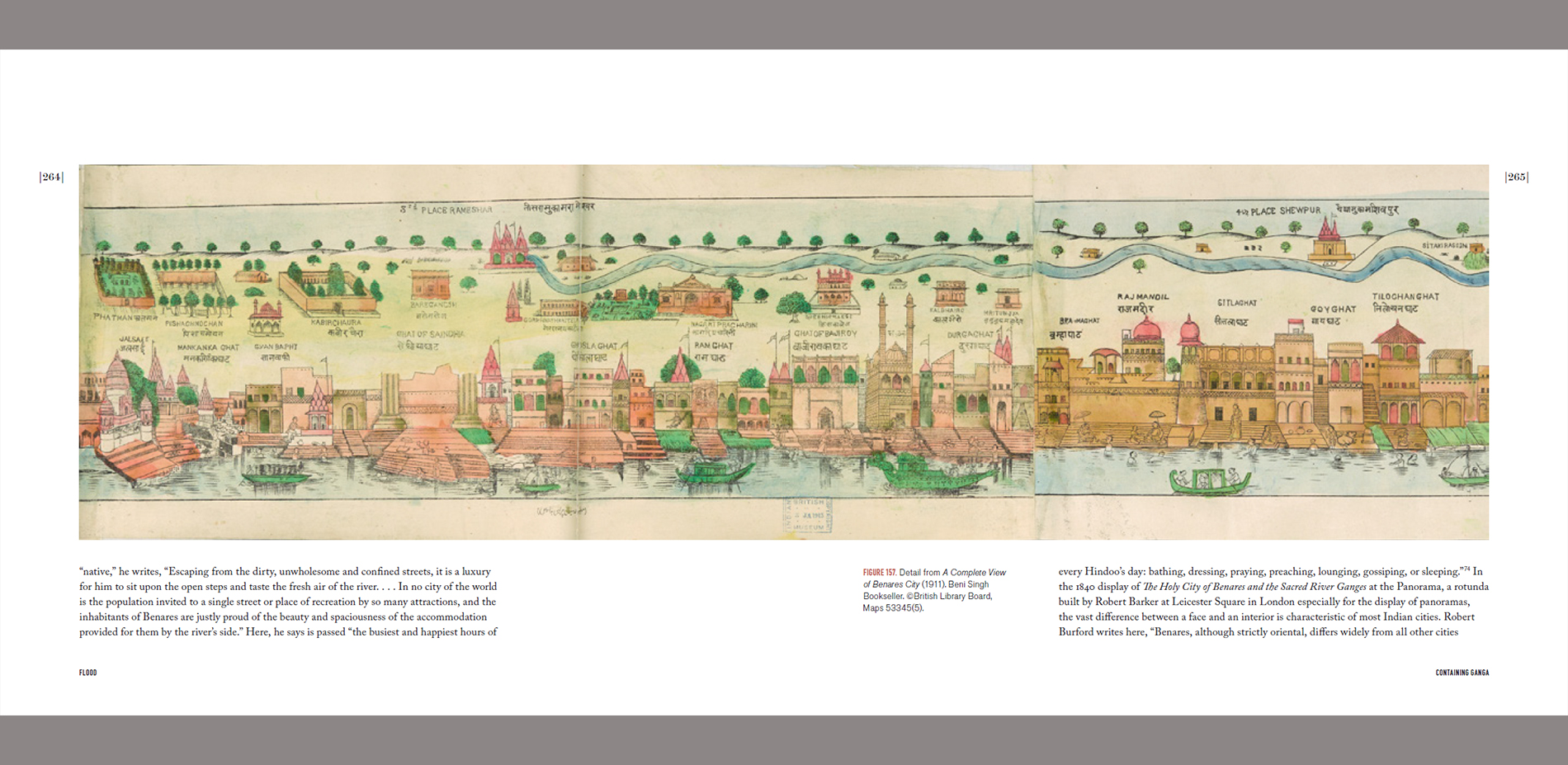

While the book interrogates the river in general, it takes a closer look at the Ganges, tracing the ways in which it has been pictured, mapped, explored, and created over millennia. But it also documents rain’s resistance to being made into a river, a resistance that points to design grounded in another moment of the hydrologic cycle.

Project Narrative

The Invention of Rivers draws attention to one of the most fundamental and enduring acts in the understanding and design of human habitation, namely, separating land and water. The line with which this separation is imaged on maps, etched in the imagination, and enforced on the ground with regulations and constructions has not only survived centuries of rains and storms to become a taken-for-granted presence; it has also been naturalized in the coastline, the riverbank, and the water’s edge. These are places subjected to artistic representations, scientific inquiry, infrastructural engineering, and landscape design with little attention to the act of separation that brought them into being. Today, however, with the increasing frequency of flood and, not unrelatedly, sea-level rise attributed to climate change, the line separating land and water has come into sharp focus with proposals for walls, levees, natural defenses, pumps, land retirement schemes, and recommendations for retreat. These responses raise questions on where the line is drawn, but they also raise questions on the separation that this line facilitates. Is this separation found in nature or does nature follow from its assertion?

The book then, makes the case that separating land from water is an act of design facilitated by a uniquely endowed line in a chosen moment of time in the hydrologic cycle. While this line can be seen at work in a number of places, the book focuses on a particular deployment of it, one that allows us to see and experience a river, an entity much appreciated across the world as a spine of civilization, an ecological wonder, a lifeline, but most of all a natural thing. By presenting the river as a product of human intention rather than nature, the book makes room for worlds without it. In particular, it makes room for rain, which the presence of the river has done much to malign and marginalize. It is, however, in a world of rain that the design of the river was initiated with the invention of the line of separation.

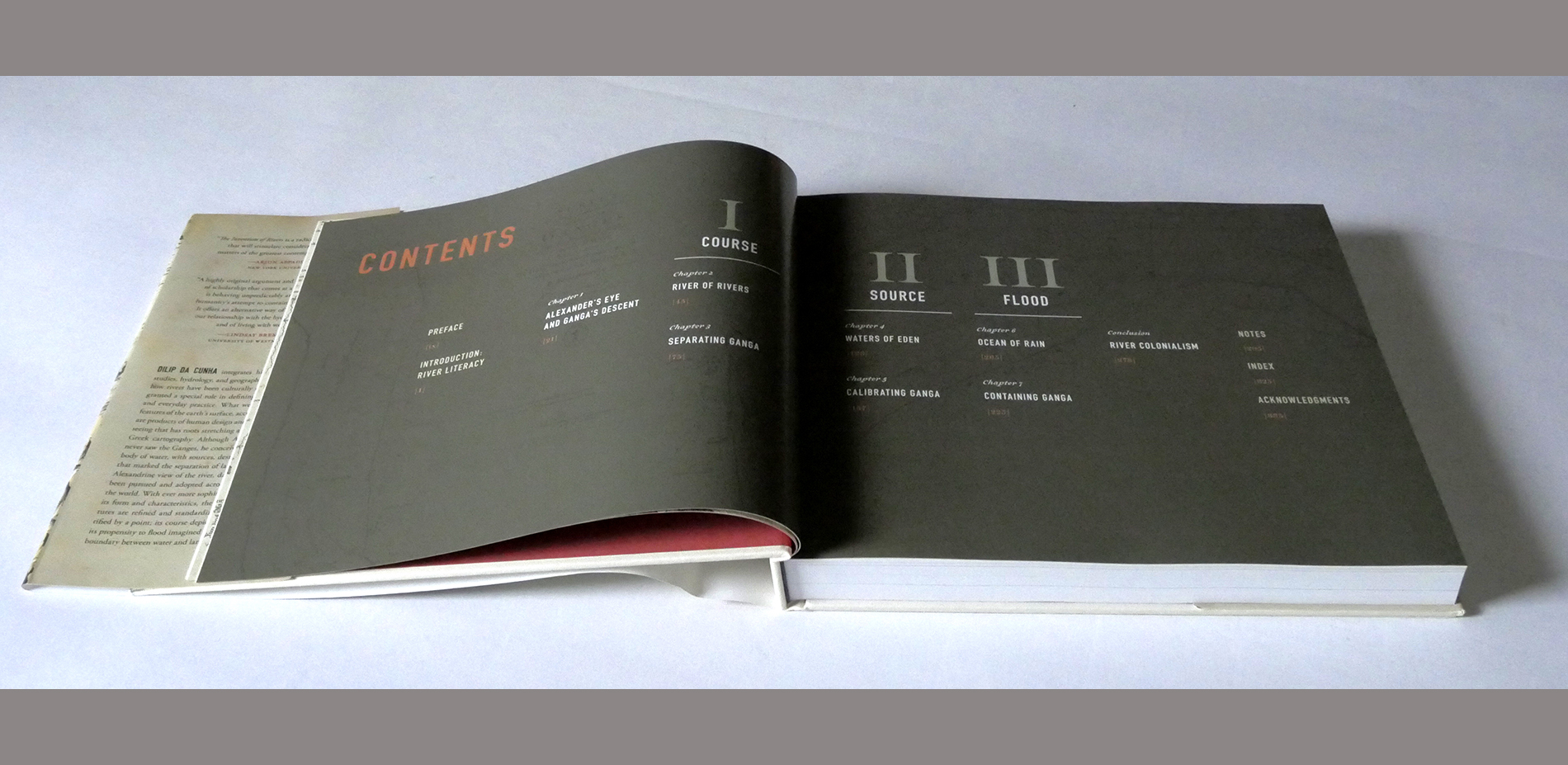

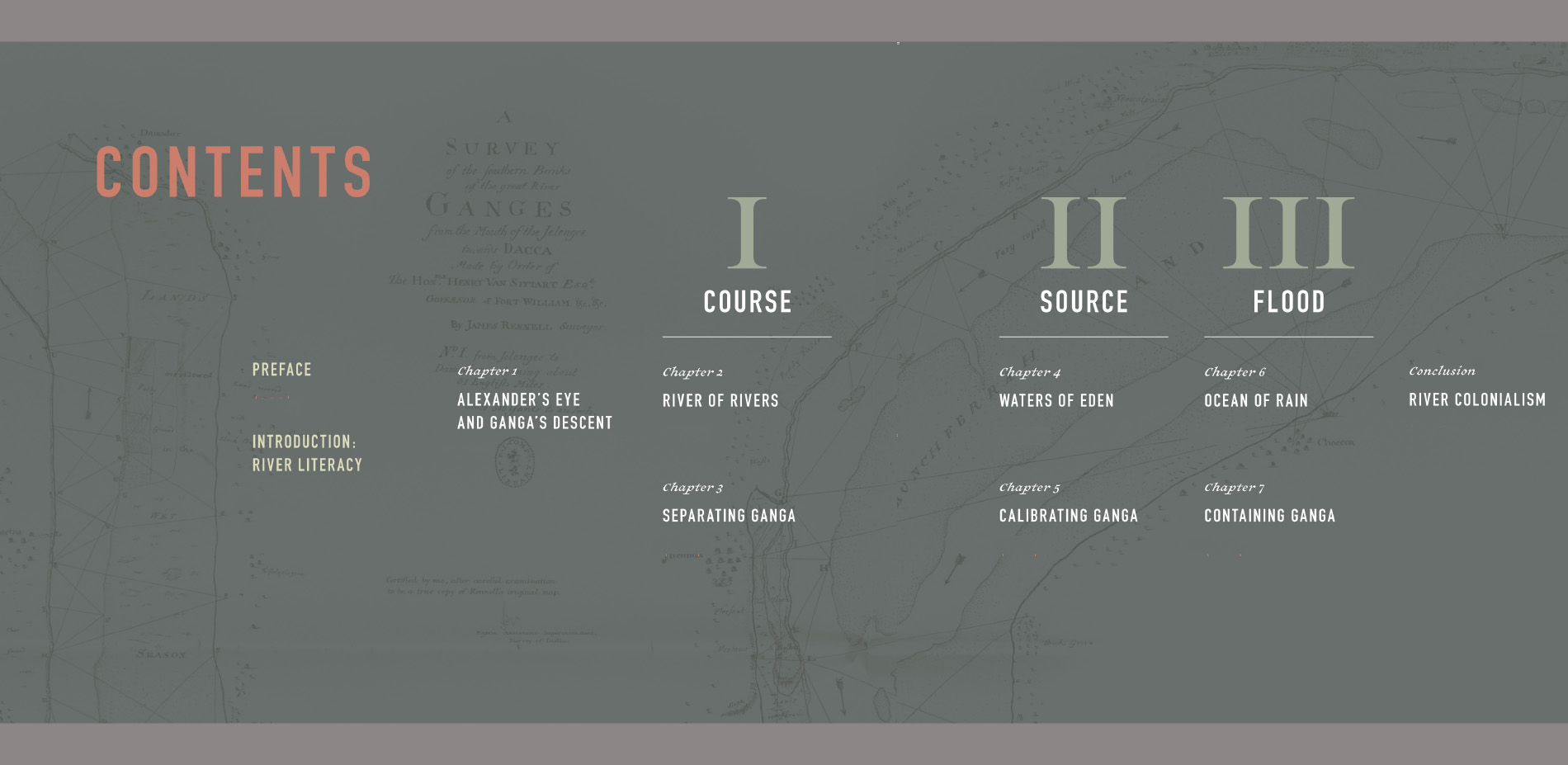

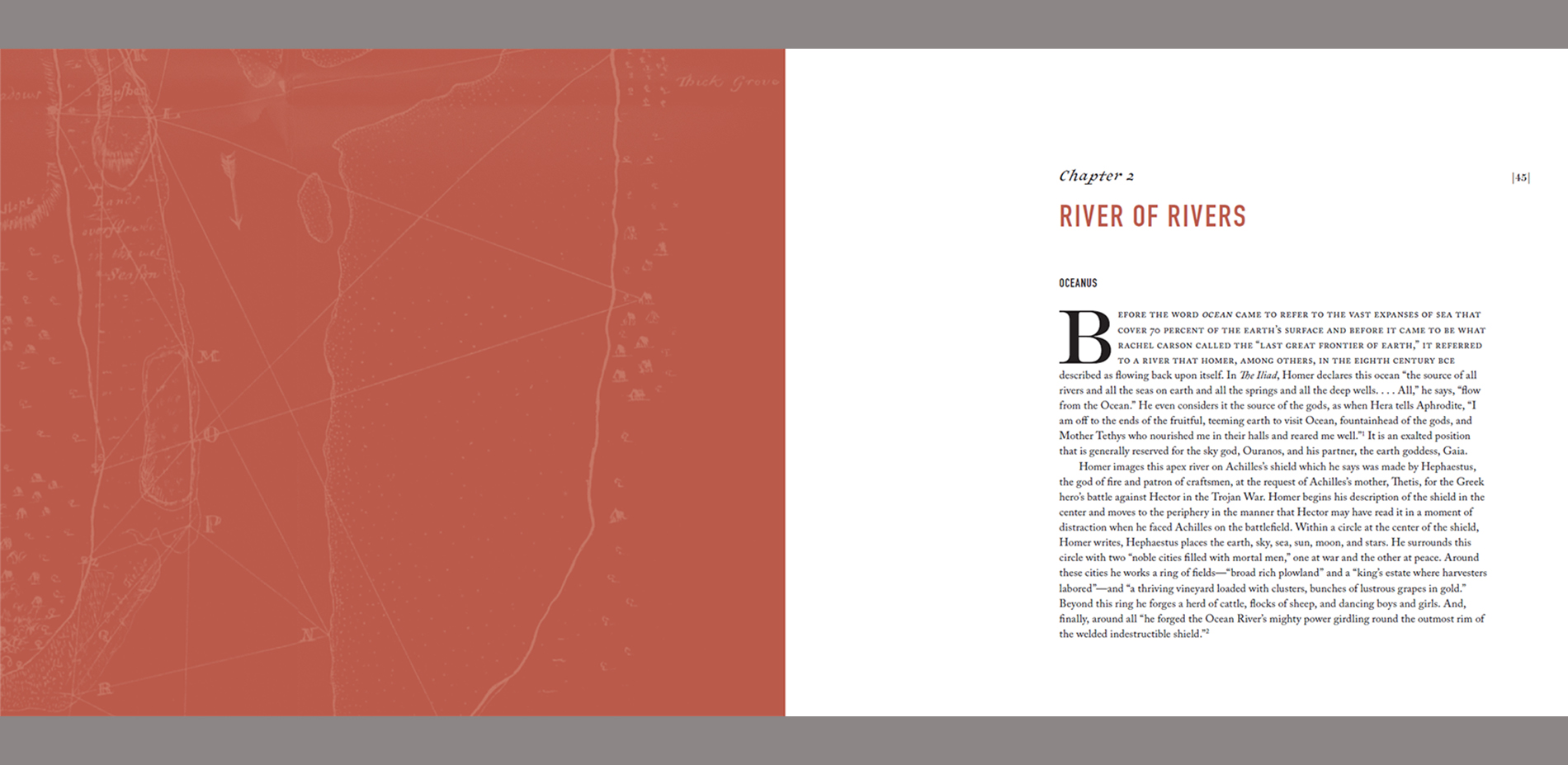

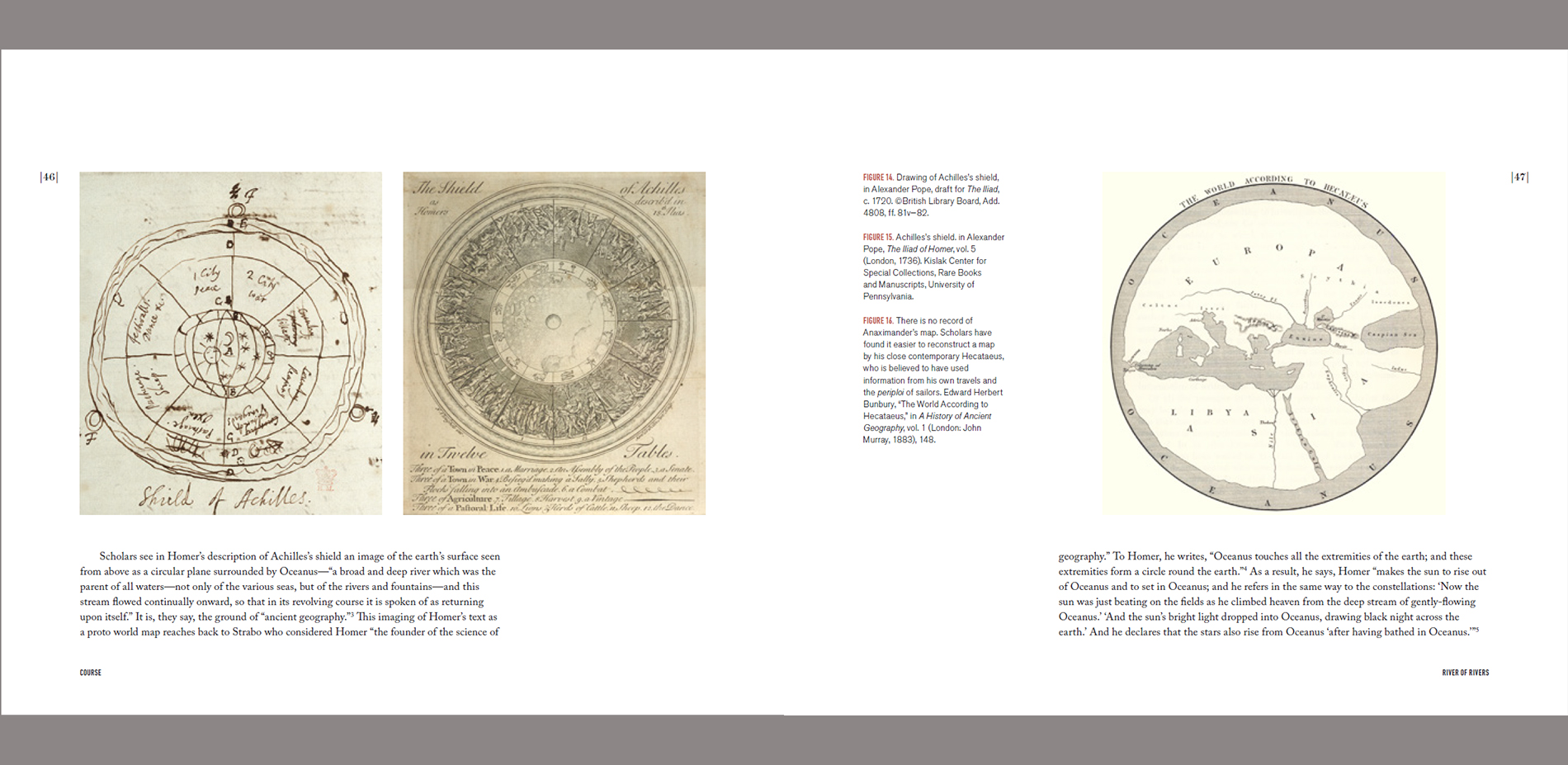

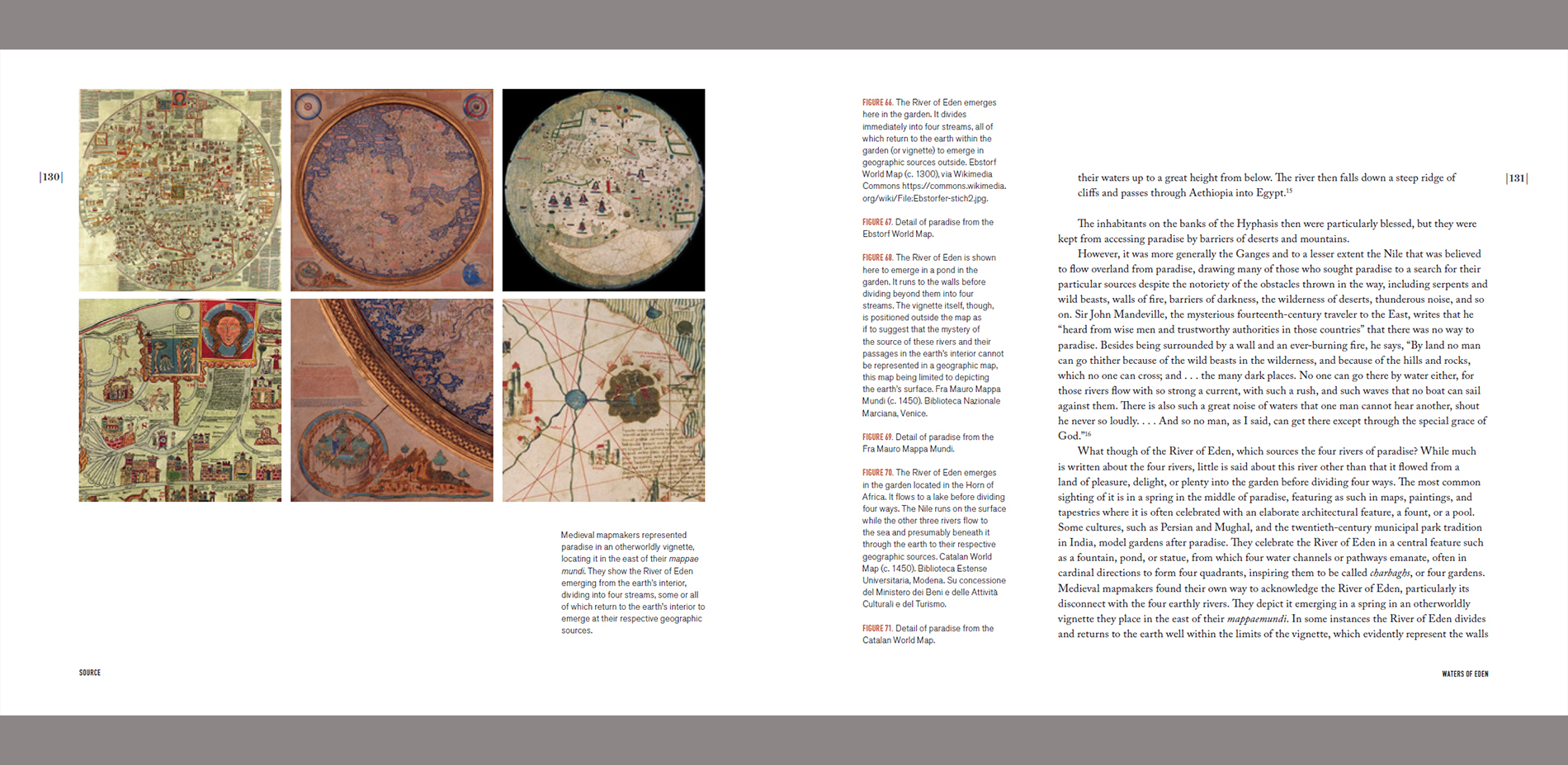

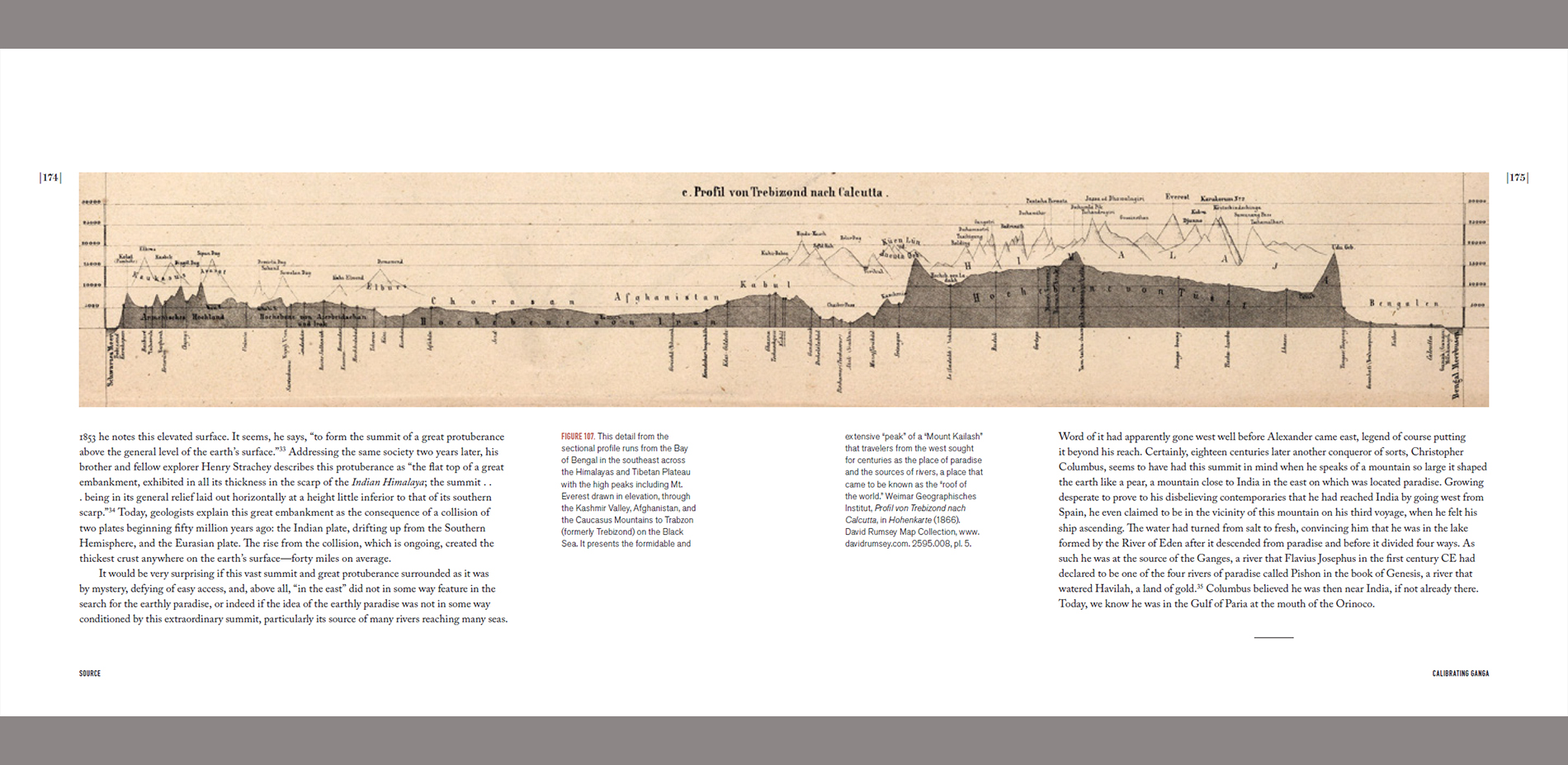

The Invention of Rivers opens with a chapter on ‘river literacy’ followed by three sections: Course, Source and Flood. Each section covers an essential of the river, a prominent feature in its definition. Critical to the sighting and understanding of these essentials is the literacy of the drawn line—its extension in a stroke, its beginning in a point, and its modification by erasure. This literacy has led the success of the river as a design project, spreading it across the world or rather creating the world that has welcomed its spread. Indeed, the capacity of the drawn line to be marked on the ground, reproduced to scale on a map, and inscribed as an image in the mind has made it indispensable to visualizing, understanding and designing habitation. It reaches into a wide array of academic fields that have all contributed in some way to making the river a corporeal thing that can be pictured, explored, mapped, enslaved, engineered, venerated and today granted rights as a living being.

The book concludes with a chapter on ‘river colonialism’. It shows how the river, created with a line, does not stop at putting water to work in the service of land by supplying it, draining it, and increasingly of late, providing it with a riverfront for real estate and development. The chapter goes further to offer another explanation for the ‘clash of cultures’ that continues to divide the world today. It suggests that the river has served conquerors, discoverers, explorers, missionaries, and settlers to not just territorialize the world, but also to colonize peoples who very likely anchored their existence in another moment of the hydrologic cycle. By calling the river into question as a weapon of colonization, the book makes room for rain as an alternative ground of habitation and imagination.

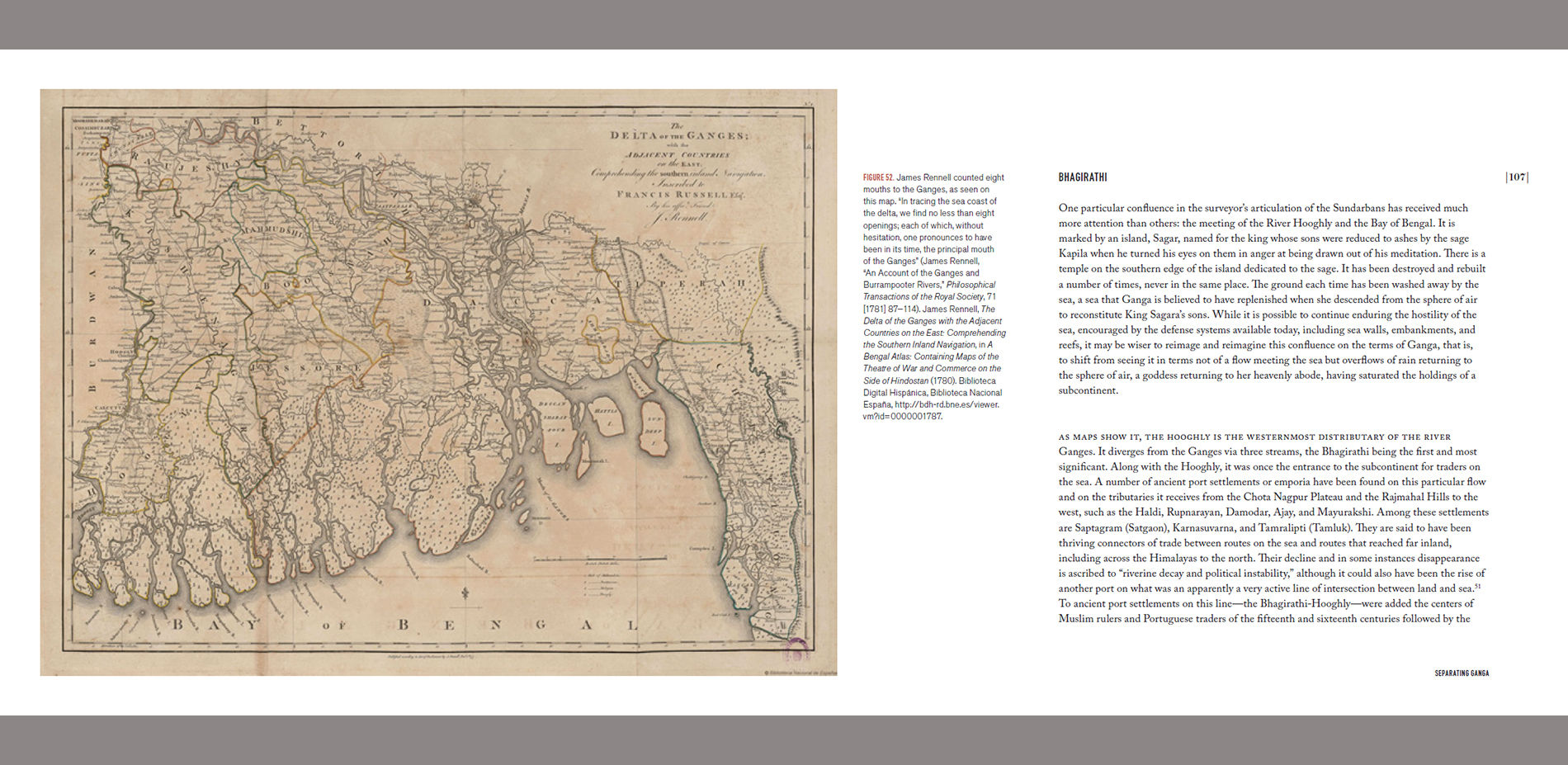

While The Invention of Rivers interrogates the river in general, it takes a closer look at the Ganges in particular. The two have evolved in mutually supportive ways. The river in general is navigated through powerful concepts on the world stage such as the hydrologic cycle, paradise, deluge, city and civilization that have built and reinforced a unique entity of water while the Ganges in particular is navigated through three select geographies of the Indian subcontinent familiar today as mountains, plains, and delta. Although used interchangeably with the word Ganga by scholars, the book makes the case that Ganga and Ganges refer to different realities, each articulated in a distinct moment of the hydrologic cycle such that Ganges is a river and Ganga is rain. While the latter is venerated for its ubiquity in the form of a goddess, the former is an introduction traceable to Alexander the Great. This scholar-monarch who came across the Hindu Kush Mountains in the 4th century BCE, was armed with not just soldiers, but also the discipline of geography that articulates place in terms of an earth surface divided between land and water. It is an articulation that makes place representable in maps; but it also makes it territorializable and its people colonizable. Even though Alexander did not reach what we know to be the Ganges today, he introduced the geographic eye that has ever since sought to contain rain to point sources and channeled courses with consequences that have produced great wealth and development, but also flood. Ganga refuses to conform to Alexander’s eye and the lines of his geographic image and imagination. She floods devastatingly each year, is terribly polluted, and her waters are increasingly contested. Her place is not a geographic surface divided between land and water, it is rather a ubiquitous wetness that reaches from clouds to aquifers. Unlike the Ganges, she does not drain off land, but rather holds in everything—earth, air, water, flora and fauna—for varying extents of time. The people in India celebrate her each year at the start of the monsoon as Ganga’s Descent.

In summary, The Invention of Rivers is an exploration of the art, science and infrastructure that has gone into materializing and naturalizing rivers on the earth surface and the role that the river has, in turn, played and continues to play in colonizing places of rain.

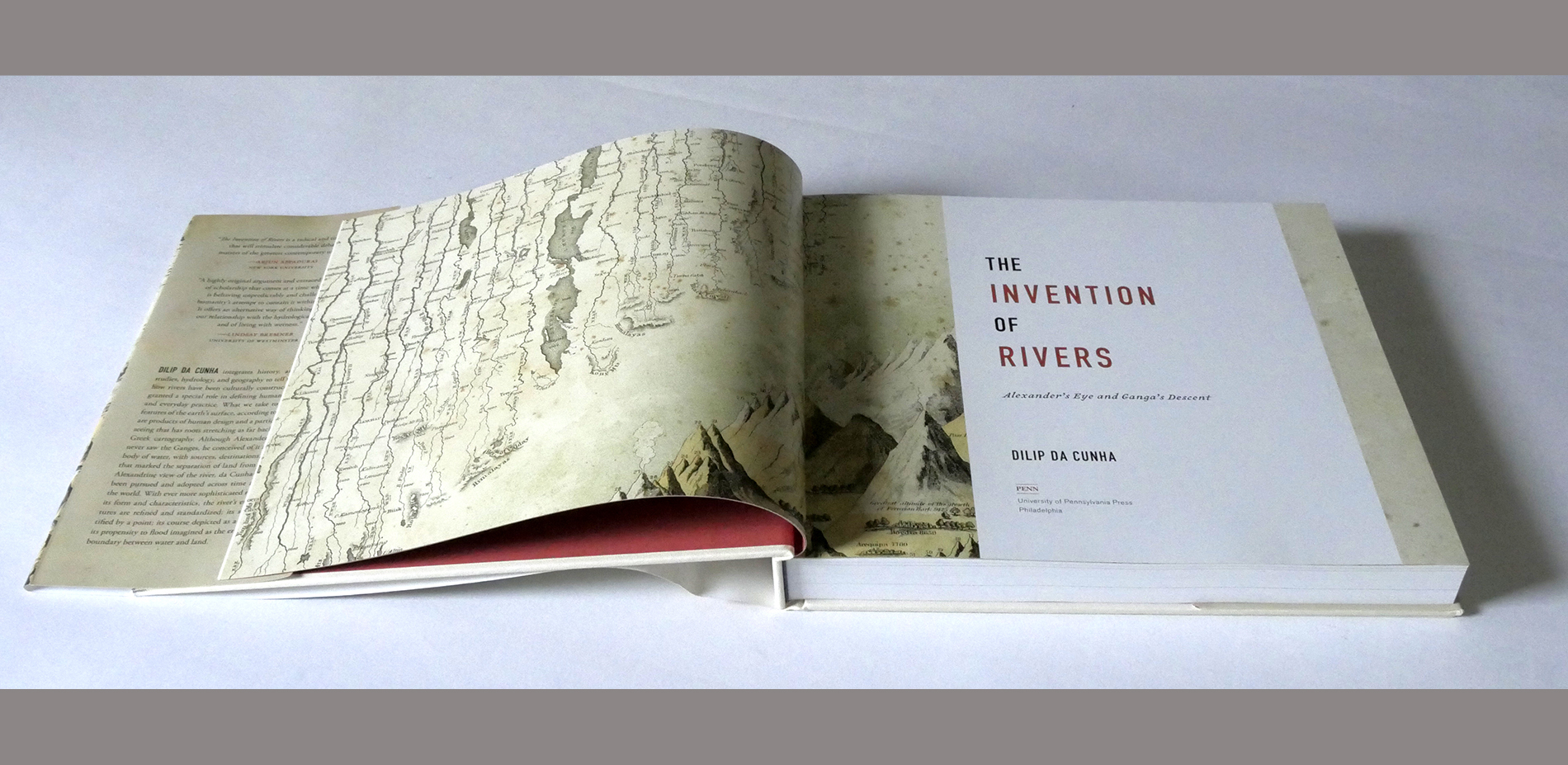

The book is written for a wide audience. It integrates history, art, cultural studies, hydrology, and geography to tell the story of how rivers have been constituted and granted a special role in defining human habitation and everyday practice. It is written in simple language and is richly illustrated with historic maps, photographs and diagrams. The river, after all, touches everyone whether through infrastructure, nature, science, landscape, environment, metaphors of flow, etc.